The burial of Jesus, image taken from the Chapel of Saint Joseph of Arimathea at the Washington Cathedral.

The following passage is excerpted from my unpublished novel, “The Mystery of the Empty Tomb.” The novel purports to be an annotated version of a long-lost manuscript written by Nicolaus of Caesarea, aide to Pontius Pilate, who was assigned to investigate the disappearance of Jesus’s body from the tomb. In chapters preceding this excerpt, Nicolaus describes the entry of Jesus into Jerusalem during the Passover festival, Pilate’s enmity with the high priests of the temple, the trial of Jesus, and his crucifixion.

The novel won the runner up award in the 2017 Best Unpublished Novel of Richmond award, but I have been unable to find a publisher interested in taking on the project. I am thinking of self-publishing. I would appreciate feedback from readers as to whether such a venture might be worth the effort.

The Sabbath day passed uneventfully. The laws of the Jews, which required them to observe a day of rest, precluded any activity but the observance of their holy Passover rites. Then, when the Sabbath ended at sunset, pilgrims prepared for the journey home. With the festival winding down, and with it any threat of disorder, Pilate and the Caesarea cohort readied for the march back to the coast. Having had my fill of Jerusalem, I yearned to return to my abode in Caesarea and to see my wife and children. Around the second hour,[1] my servant Menander had loaded my belongings onto a mule when a commotion occurred at the front gate to Herod’s Palace.

Joseph of Arimathea was loudly demanding an audience with Pilate. The prefect, preoccupied with preparations for the march, was not available. Then Joseph sought me out. “Jesus is gone,” said he. “He is missing from the tomb!”

“How come you by this information?” asked I.

“The followers of Jesus visited the tomb this very morning. They found that the rock seal had been rolled aside. When they entered the tomb, they saw his linen garments strewn about. But he was gone and is nowhere to be found!”

Without question, the situation warranted Pilate’s attention. Grave robbery was a crime under Roman law. Indeed, it was so common in Galilee that Herod Antipas had posted an inscription in Sepphoris for all to see.[2] The offense was known to occur in Judea and Samaria as well. Most often, thieves sought the jewelry and ornamental items buried with the dead. But it was not unknown for grave robbers to steal the body itself, usually for necromantic purposes.

I interrupted Pilate’s deliberations with the primus pilus.[3] “Dominus, I beg a moment.”

“I am occupied,” Pilate said sharply. “Mind your place.”

Pilate was not moved easily to anger but when his wrath was kindled, no man would wish to stand before him. Yet he had not engaged me to act his toady. At the risk of public rebuke, I persisted: “It is Jesus of Nazareth, Dominus. His body is gone!”

The words had the same effect as if I had slapped his face. Pilate wheeled his horse around and faced me. “Get on with it, then.”

I repeated what Joseph had told me.

“Summon the priest immediately,” said the prefect. “I would hear this from his own mouth.”

Pilate held his audience while mounted upon his war horse. Even at his age, he made a formidable and warlike figure. Bowing, the councilor repeated the story he had told me. Pilate cut to the heart of the matter. “Who has done this?”

“I know not, eminence,” said Joseph.

“Whom do you suspect?”

“I have no grounds to single out any party,” said Joseph. “I can only speculate.”

“Then give me the benefit of your conjecture,” ordered Pilate.

“We angered the high priests when we laid Jesus in the tomb,” said Joseph. “Perhaps they wished to see his body desecrated and defiled. Perhaps they removed it so the tomb would not become a shrine.”

“What think you, Nicolaus?”

“That explanation is as plausible as any,” said I. “But we know so little that I cannot say with certainty.”

“We cannot let this crime go unpunished,” said Pilate. “Jesus is too well known. Word will blow through Judea like a sirocco. I cannot tolerate such an insult to Roman law. Furthermore, if there is any chance that Caiaphas was behind this criminal act, I will know of it.”

Pilate did not need to elaborate. I could read his thoughts as clearly as if he had carved them into a stele. If we could implicate Caiaphas and Annas in the robbery of Jesus’ tomb, the priests would have no more hold over him. Grave robbery was punishable by death throughout the empire by the order of Tiberius himself. Pilate could dangle the threat of arrest and execution over the priests like the sword of Dionysius.[4] They would never dare challenge him now by sending a letter to Rome.

Pilate continued: “I want you to get to the bottom of this. Conduct an inquiry. Question whomever you must. Do not rest until you have uncovered the culprits.”

At this command, I was dismayed. I had important affairs to settle with the steward of my estate back in Caesarea, and I longed to see my wife and children. Some men could happily march on long campaigns or voyage to far-off seas but I was not one of them. The luxurious apartments of Herod’s palace were no substitute for my own hearth, and no tumble with a tavern whore was as satisfying as the embrace of my loving Hestia. But I saw the sense in staying in Jerusalem to sniff out the hoodlums who absconded with Jesus’ body before the scent went cold.

“I shall do as you order, Dominus,” said I.

“Find those responsible and I will reward you well,” said Pilate. “Connect the crime to Caiaphas, and I shall make you a rich man.”

*****

Joseph guided me to Jesus’ sepulcher. We arrived to find some curiosity seekers loitering near the doorway, too timid to enter. Pilate had granted me an eight-man detachment[5] from Longinus’s centuria – the same men who had escorted Joseph’s burial party to the sepulcher – and I put the guard to good use. The decanus, an energetic young man by the name of Sextus, chased away the onlookers before they had a chance to pilfer anything, and set a guard at the tomb so I could investigate the scene without distraction.

The sepulcher was set in a cliff of fractured, crumbling rock from which patches of brush sprouted like the hair of a mangy dog. The entrance lacked ornamentation of any kind – no columns, no entablature, not even a door — just a hole cut into the cliff and a heavy, disk-shaped stone that could be rolled aside to provide admittance. The entrance was low, requiring visitors to stoop in order to step inside.[6]

“Hardly fit for the king of the Jews,” said I.

“It was the closest sepulcher at hand,” said Joseph. “A funerary guild dug it for Jerusalemites whose families own no sepulcher of their own. We had no time to look for a more suitable place.”[7]

“How far did you progress in your burial preparations?” I asked.

“We cleansed Jesus of blood and grime and we swaddled him a burial shroud. Then, for lack of time, we left,” said Joseph.

Ducking as I entered the tomb, I stepped into a gloomy chamber where I was immediately assaulted by a stench of dust, decay and sickly sweetness. As my eyes adjusted to the dark, I discerned nothing but shadows. Although reason told me that spirits did not exist, there was no knowing such a thing for certain. If lost souls did linger upon the face of the earth, it would be in a place like this manor of the dead. For a moment, a sense of such dread seeped into me that I thought of stepping back into the light. I understood why those addicted to superstition – fearing demons and vengeful spirits – would hesitate to enter. Or, once they had entered, why they would rush to leave.

Gradually, my anxiety lifted and my sight improved. On either side of the room, ledges were cut into the walls, forming shallow, waist-high alcoves with arched ceilings where bodies could be placed and attended to. Upon one such bench lay a burial shroud, rumpled as if it had been haphazardly deposited there, while a smaller linen lay on the floor. [8] Those were Jesus’ burial linens, I expected, and I would examine them momentarily, but first I determined to take a quick tour of the tomb. On the far side, the chamber opened onto a passageway from which radiated several dozen shafts. Some were empty; others were closed with tight-fitting limestone seals. Inside each closed compartment was a decaying body. Deeper into the sepulcher where light barely penetrated, I dimly perceived shelves lining the passageway, upon which patrons had stored several ossuaries of wood and stone. It was the practice of the Jews, once the bodies in the shafts had fully decomposed, to shift the remains to space-saving bone boxes. Only a few such ossuaries were in evidence, and I saw no sign of recent activity.

I pondered a moment how some Jews believed in an afterlife while others did not. The aristocratic Sadducees had a saying, identical to what we Epicureans believe: “From dust to dust, ashes to ashes” – just as there was nothingness before life, there was nothingness after. There was no reason to fear death, for there would be no more pain than we felt before we were born. But the mass of the people, who suffered much during their lives and yearned for something better, deluded themselves that their souls would survive the disintegration of their bodies and upon the resurrection would ascend into heaven and live in the house of their lord, Yahweh, with all manner of angels, heavenly hosts and long-passed friends and family members. They believed this with no evidence whatsoever. No one had visited this place and returned to tell others of what they had seen. It existed only in peoples’ imaginations. Such was the power of men to believe what they wanted to believe.

Returning to the front of the tomb to inspect the two pieces of burial apparel, I conceived of two theories to explain the placement of the garments. The first was that Jesus had recovered from seemingly mortal wounds and removed the linens himself. But I had no explanation of how he might have budged the stone that sealed the door – an impossibility from inside the tomb, especially for a man who had been close to death – nor why, had he contrived to escape, he would have left the linens behind rather than use them to conceal his nakedness. The second possibility, which I found far more plausible, is that someone else moved the stone, entered the tomb and found a shroud-covered body lying on a bench. Wanting to ascertain that the corpse was that of Jesus, the intruders first removed the napkin wrapped around his head and dropped it upon the floor, for they had no further use of it, and then they pulled back the shroud to look upon the body and face to confirm Jesus’ identity.

I thought it curious that the burglars, whoever they were, had left the shroud behind. The linen cloth was finely woven and a thing of value. Had the visitors been reverent disciples of Jesus intent upon relocating his body to a more worthy location, surely they would have taken the time to wrap him in the shroud and wind the cloth around his head, as Joseph and Nicodemus had done. But instead, the interlopers abandoned the linens. That suggested to me that the removal of Jesus’ body was an act of theft. If the robbers had been as discomfited as I was upon entering the tomb, perhaps fearing retribution from Yahweh, demons or the spirits of the dead, they would have fled with Jesus’ body as soon as they could, not caring if they left the linens behind.

I summoned Joseph into the tomb. “Just to confirm,” I asked, “are these the shroud and napkin that you placed on Jesus?”

“Yes,” said he.

“What about the perfumes and spices?” I asked. “Did you leave them here in the tomb?”

“No, Nicodemus gave them to the Galilean women outside the sepulcher on the day of the crucifixion,” said Joseph. “It was their intention to return this morning and finish the burial preparations that we could not complete.”

I was astonished that Nicodemus would hand over such a treasure to someone he did not know. “What assurance did he have that the women would not abscond with the spices?”

“You will have to ask him about that,” said Joseph. “As for myself, I did not consider the possibility. One of the women was Jesus’ mother. The others were obviously devoted to him and they were mourning. It seemed appropriate that those who loved Jesus complete the ablutions.”[9]

“What is your conclusion from seeing the burial linens lying about in this manner?” I asked.

“We did not leave them this way,” said he. “Whoever took the body of Jesus must have stripped them from his corpse and laid them aside.”

“The linens are expensive, are they not?” said I.

“Indeed, I would think so,” said he, “although only Nicodemus could tell you what he paid for them.”

“Whoever took Jesus’ body was not a friend,” said I. “If the intruders revered Jesus and were intent upon moving him to another tomb, surely they would have taken his burial garments as well. And surely they would have informed those who buried them of their actions.”

“That stands to reason,” said Joseph. “I have heard nothing in that regard.”

“If the culprits did not take Jesus for a reverent purpose,” said I, “then it follows that they removed him for a malign purpose. We are dealing with grave robbery here.”

“I cannot fault your logic,” said Joseph, “although I desperately hope that you are wrong.”

*****

I could think of little else that could be accomplished at the sepulcher. Determined to have the linens left precisely where the grave robbers had placed them, should I need to revisit the scene, I resolved to close the tomb to snoops and relic hunters. I ordered Sextus, commander of my escort, to seal the sepulcher and post a two-man guard to watch the tomb around the clock. Then I resolved to question the Galilean women as soon as I could.

The Herald-Progress and the Caroline Progress, community weeklies serving Hanover and Caroline counties, are going out of business. The final editions will be distributed today.

The Herald-Progress and the Caroline Progress, community weeklies serving Hanover and Caroline counties, are going out of business. The final editions will be distributed today.

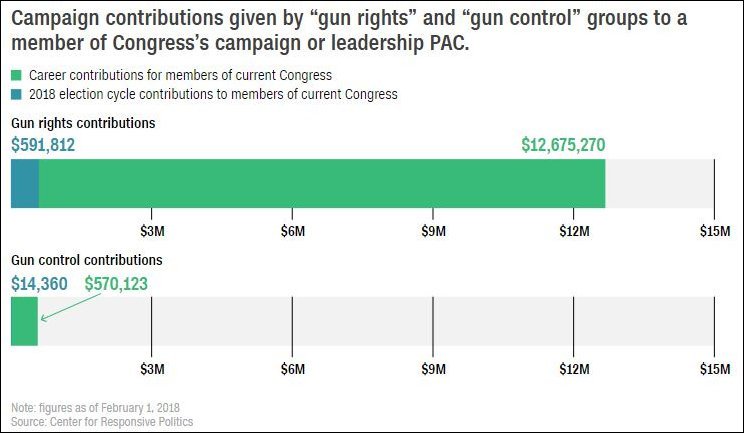

So, I listened this weekend to some of the speeches in the “March for Our Lives” protest against guns, and heard a lot of criticism of the National Rifle Association for buying votes through its enormous campaign contributions. Then I saw

So, I listened this weekend to some of the speeches in the “March for Our Lives” protest against guns, and heard a lot of criticism of the National Rifle Association for buying votes through its enormous campaign contributions. Then I saw

I visited my daughter Sara the other day and was amused to note that delivery services had dropped off two cardboard boxes in front of her house. When I stepped inside, there was a third box, still unopened. Three packages delivered in one day. Wow, thought I. My wife and I might average one delivery per week. Upon my further inquiries, Sara revealed that she also had begun ordering her groceries online and having them delivered to her doorstep as well.

I visited my daughter Sara the other day and was amused to note that delivery services had dropped off two cardboard boxes in front of her house. When I stepped inside, there was a third box, still unopened. Three packages delivered in one day. Wow, thought I. My wife and I might average one delivery per week. Upon my further inquiries, Sara revealed that she also had begun ordering her groceries online and having them delivered to her doorstep as well.