by David J. Toscano

For over a month, Virginia’s legislature and governor have been embroiled in a “two scorpions in a bottle” fight over the new biennial budget, which must be passed by June 30, 2024, to fund the government. Last Wednesday, each of them loosened the cork in the carafe. After Assembly-initiated discussions with the governor, Virginia leaders showed, for one moment at least, how the commonwealth operates differently from Washington, D.C. Rather than force Youngkin to take the political hit from vetoing the first Virginia budget in recent history, the House of Delegates used an unusual procedural move, and killed it themselves. All sides committed to producing a new budget and to return on May 15 to pass it. As Churchill once said, “Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.”

Budget battles in the commonwealth are not unusual, but this one has been unique, both in the number of changes Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin proposed to the bipartisan spending plan, and in the rhetoric that has accompanied the process. Youngkin called the bill a “backward budget” and traveled the state on this theme. Legislators fired back, did their own tour, and likened Youngkin’s actions to “what spoiled brats do when they don’t get what they want.”

Last Wednesday, both sides returned to Richmond for the “reconvened” or “veto” session. The governor had vetoed a record number of bills, including measures to protect reproductive rights and enhance gun safety. Since overriding a veto requires a two-thirds vote, the governor was successful with every veto.

The fight over the budget bill is different. Youngkin, like governors in 44 states and unlike our U.S. President, has the power to “line-item veto” specific provisions in the budget. His targets were thought to be a tax on digital services he originally proposed and language that requires the commonwealth to rejoin the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). But he abandoned this approach when legislators shrewdly drafted these provisions to make a line-item veto legally problematic.

It does not matter whether you are a Republican or Democratic governor; legislative power is clear in the budget process. Several years ago, Governor McAuliffe learned how crafty legislative budget writing can frustrate key executive goals. The governor hoped to expand Medicaid through the budget, but Republican leadership was resistant, and explicitly included language in the budget to prevent it. McAuliffe attempted to line-item veto that provision, only to have House Republican leadership opine that the Governor had no such constitutional or statutory power to do so. When it comes to the budget, legislators enjoy proclaiming “governors propose; the legislature disposes.”

A RECORD NUMBER OF VETOES

Youngkin instead proposed a record number of 233 separate amendments to the budget bill. With Democrats still fuming over Youngkin’s rhetoric and vetoes over the last month, pundits predicted that the governor would lose any substantive vote. He would then face a difficult choice. He could sign the budget “as presented,” or veto the entire plan and throw the process into turmoil.

The legislature held–and continues to hold–most of the cards in this budget game. But instead of playing hardball, they instead threw the governor a lifeline and opened an opportunity for compromise. And there is a deal to be had. Perhaps the legislature kills the digital sales tax in exchange for a deal to keep the Commonwealth in RGGI. Fortunately, the commonwealth’s finances are strong enough to justify a spending plan that includes more investments in education and mental health.

The July 1 deadline for a new budget still looms large. Without progress, government agencies and local governments will soon scramble to construct contingency plans. If budget uncertainty continues too long, it might even prompt Wall Street to revisit Virginia’s celebrated Triple A bond rating, a fixture for more than 50 years. A lot is at stake. Ultimately, the legislature will get most of what it wants, even if it takes a special session to do so.

STATE GOVERNMENT SHUTDOWNS ARE RARE

The odds of a Virginia government shutdown remain slim. There have been 21 federal shutdowns in the last 50 years, but state shutdowns are relatively rare, the most recent of which included Illinois for 6 days, (ended when the legislature overrode the governor’s veto) New Jersey for 3 days and Maine for 4, all in 2017.

The closest Virginia has come to shutting down was Tim Kaine’s first year as governor in 2006, when the Republican-controlled House and Senate deadlocked on transportation funding. As the clock ticked toward a July 1 shutdown, Kaine drafted contingency plans to keep government open, but understood that some might not survive legal scrutiny. Fortunately, he never had to use them. The Assembly compromised and sent the governor a budget, just two days before the deadline. Most governors face limited options when confronted with a potential shutdown. Only three — North Carolina, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin — allow spending to continue past the deadline.

THE MOST POWERFUL LEGISLATURE OF ALL?

Youngkin is now learning what his predecessors discovered a long time ago — that the legislature is the strongest branch of government, and the commonwealth’s is perhaps the strongest of all the states.

The legislative advantage is found in the Virginia Constitution. Virginia is the only state where the chief executive cannot serve consecutive terms, making it difficult for governors to extract concessions from legislators who will serve much longer. In their first year, they are learning the system. By their third year, they are viewed as “lame ducks.”

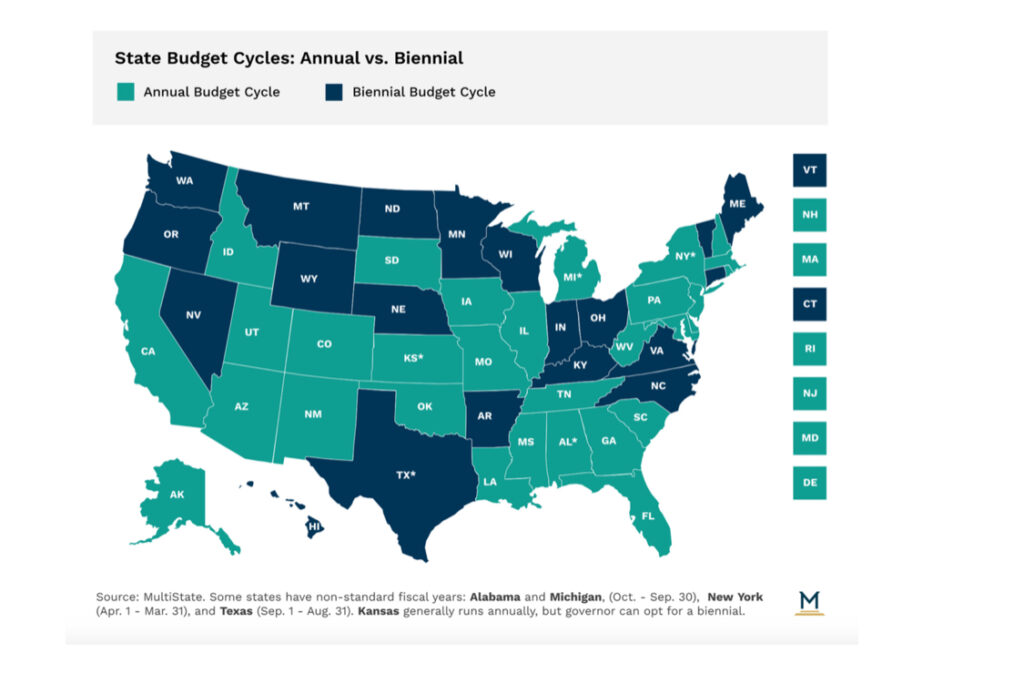

We see this in the most important document of state governance – the budget bill. Virginia is one of only 19 states with a 2-year budget. In most states, newly- elected governors submit a budget at the beginning of their term. Not so in Virginia! When Virginia governors take office, they are immediately confronted with a two-year budget prepared by the previous chief executive. Newly sworn governors can propose budget amendments, but they are painting on a canvas that has been provided by their predecessor. The only budget plan that is uniquely theirs is created at the end of their second year in office. In their final year, they prepare another two-year budget, but they leave office before the legislature debates it in a new session with a new governor. This gives the legislature an edge in budget deliberations, and further fuels the adage frequently heard in Richmond that “governors come and go; the legislature is forever.”

The commonwealth is now considering the only budget that is Youngkin’s alone. His best chance to leave a legacy is this budget; but his relationship with the legislature has made this problematic. The Alexandria arena proposal proved a disaster, and significant fence-mending will be needed for his priorities to be implemented.

VIRGINIA LEGISLATORS CONTROL THE JUDICIARY AND KEY REGULATORS

The power of the Virginia legislature extends beyond appropriations. The body has greater appointment powers than most state legislatures and can derail key nominees that the governor desires. Virginia’s State Corporation Commission (SCC) is a good example. Almost its own branch of government, its decisions affect everything from utility rates to insurance regulation. SCC judges are solely appointed by the legislature. In other states, not only do similar bodies have less power, but the regulators are either elected by citizens or appointed by governors.

In addition, our legislature appoints the entire judiciary. Judges in most states — including state supreme court members — are either appointed by the governor or elected by the citizenry.

This is not the case in Virginia. The commonwealth and South Carolina are the only states where the legislature has total control of these selections. A Virginia governor has the ability to make appointments to the state Supreme Court while the legislature is in recess, and traditionally the Assembly has acceded to these recommendations. But it retains the ultimate power. When Terry McAuliffe appointed the highly qualified Jane Marum Rouch to the Supreme Court during a legislature recess in 2015, the Republican-controlled Assembly removed her when it reconvened–simply because it had the power to do so.

The system appears almost quaint by comparison to the rough and tumble statewide political campaigns for state supreme court positions recently witnessed in Wisconsin and Pennsylvania. (I will have a post on this soon). As more fundamental rights are litigated in the state courts, greater attention will be paid to the legislature’s choice of judges.

Over the next month, Gov. Youngkin and the legislature will develop a new budget. Expect the Assembly to get most of what it wants. And it will continue to exercise powers that its colleagues in other states cannot, arguably making it the most powerful legislature in the country.

David J. Toscano practices law in Charlottesville and served 14 years in the Va. House of Delegates. He is the author of Fighting Political Gridlock: How States Shape Our Nation and Our Lives, University of Virginia Press, 2021, and Bellwether: Virginia’s Political Transformation, 2006-2020, Hamilton Books, 2022.

You can see his other writings at Fights of Our Lives: What Is Happening in State Politics and Policy and How It Affects Our Democracy.

This column is republished with permission.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.