by Jon Baliles

by Jon Baliles

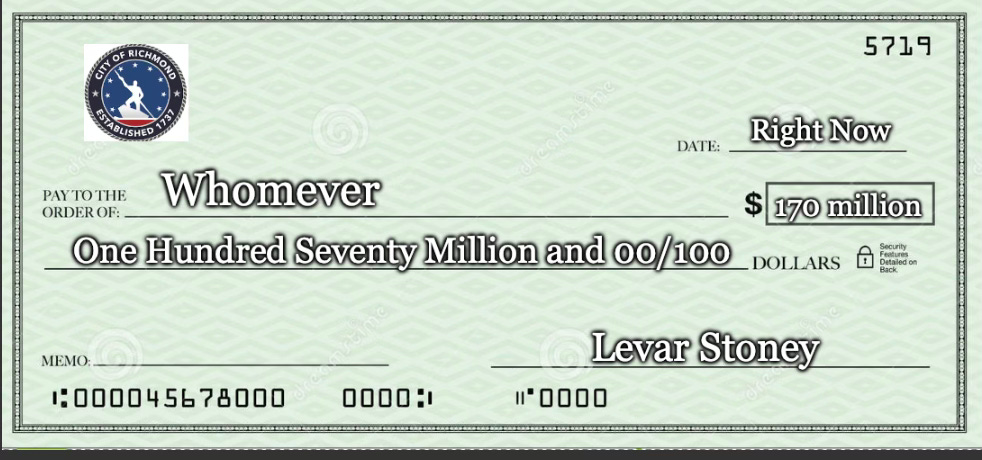

The entire saga of the development of the Diamond District project in Richmond has come full circle in the last 18 months, as Mayor Levar Stoney, desperate for an economic development win after the failure of his Navy Hill boondoggle and two failed casino referendums, has rounded the bases trying to get a baseball stadium built before the franchise was going to be moved by the powers at Major League Baseball (MLB). Finally scoring a run, however, will come with a cost: $170 million to be exact, because that is how much debt the city will issue to pay for building the stadium and surrounding infrastructure for the rest of the Diamond District development.

The big news broke last week about the new plan to build the baseball stadium but is also being accompanied by a new financing and development structure and procedures. The announcement unfortunately pre-empted the planned Part 3 of our baseball stadium series, which explained that, at this late date, the only option left to get the stadium built in time and not have MLB yank the franchise was for the city to issue general obligation (G.O.) bonds. That was the only evidence MLB was going to accept to prove the money to build the stadium was actually there and construction could actually begin, because all the talk from the city had been just one missed promise after another, and delay after delay.

The bomb was set to explode and the Mayor and Chief Administrative Officer (CAO) played the last card they had left. They will put the onus of the debt and risk all on the city’s shoulders, issue the debt quickly and get the shovels turning to meet the deadline. But that is not at all how this process began, and it has changed drastically in the many months the city spent dithering.

Back in September 2022, Jonathan Spiers (pronounced Spy-ers) wrote in Richmond BizSense that the Mayor planned to have Council vote on the deal later in 2022 with the goal of work starting on the new stadium early [in 2023] and wanted to open the stadium in the spring of 2025. The plan called for the entire 67-acre Diamond District property to be a tax increment financing district (TIF) that would use all the taxes generated inside it to help pay for the development.

According to the city’s term sheet with RVADP at that time, “The redevelopment of the Diamond District site is intended to be financially self-sustaining, meaning that the new development in the Diamond District will generate enough tax revenue to pay debt service for Community Development Authority (“CDA”) bond financing and additional municipal services that may be required to support the new development.”

The term sheet also indicated that the bond financing “shall be nonrecourse to the City; therefore, not requiring a moral or financial obligation from the City” and would include a special assessment requirement that “obligates the Developer and other future landowners within the District to pay all debt service payment shortfalls in the event the revenues generated in the CDA District are not sufficient to pay debt service payments.

Boxer Mike Tyson was credited with saying that everyone has a great plan until they get punched in the face, and that is certainly applicable here. Eight months after the city announced the roadmap to the Diamond District, they got hit in the face by interest rates. It took until late April 2023, when the city announced that the deal with the developer had been finalized, but some major changes were also announced.

The stadium would not open until 2026, a year later than planned, and a new TIF district would expand well beyond the 67 acres included in the original Diamond District to surrounding development in order for the city to fund infrastructure improvements in the District. The city noted that rising interest rates made the project’s original math unworkable and funding was now to come from the expanded TIF district revenues as well as other sources, including public utilities enterprise funds and General Obligation Bonds. The city also announced the entry of the Economic Development Authority (EDA), which would sell land to the developer but also would control the land under the stadium and be responsible for the leases with the Flying Squirrels and VCU baseball.

But except for rezoning the Diamond District property, the city didn’t do any of the other required tasks over the course of the next year, such as create the CDA or finalize stadium lease agreements. Fast forward to last week and suddenly, the Mayor and CAO announce an entirely new plan to issue $170 million in general obligation bonds that will put all of the risk of the project on the city’s shoulders as well as overhaul the development strategy and structure of the deal — oh, and they want City Council to approve it in two weeks.

As Spiers reports in BizSense, the city now says interest rates are so high that the best way to proceed and “save” money over the 30 years is for the city to issue $130 million in debt to build the stadium and $40 million of debt to pay for the needed infrastructure and bear the risk of the project producing enough tax revenue to pay the debt service. Municipal G.O. bonds offer the lowest interest rate we can get and the city now claims the switch will save $215 million in debt over the 30-year bond term because of the city’s strong credit rating.

In fact, the Mayor and CAO are now intimating that this plan was always the best way to do it because of how much it saves us with the low rate compared to their original plan — but it ignores the other side of the coin, which places all the risk on the city; if the development does not produce enough revenue to pay the debt, then the city has to come up with the money through taxes or deferring other projects. Of course, Stoney & Company forgot to mention that had their “new” discovery just been implemented two years ago when municipal interest rates were about half as much than the 4.5%-5% range they are in today, the “savings” would be astronomical — but the risk would still be on the city’s shoulders.

Regardless, CAO Lincoln Sanders told BizSense last week after putting forth the proposal that will put $170 million of city funds at risk, “We are recommending this because we think it is fiscally sound and, in the end, lower risk for the city.”

The city received an “analysis” from Davenport & Co. which serves as the city’s financial advisor. Totaling just six pages in length, it is less of an “analysis” and more of a cheerleading document that can be found on page 200 of the ordinance introduced last Monday and will be approved in another week’s time since Council has already unofficially signed off on the deal.

In the document, Davenport notes that the interest rates for bonds using the original CDA financing plan are about 8%, twice what the city can get by issuing G.O. bonds. Using the CDA financing plan would require about $314 million of debt service to pay off the bonds but using the “new” plan would only incur about $110 million of debt service and thus, “save” the city $215 million in debt service (of course, those “savings” do not include the cost of delays in funding to other projects using the city’s limited debt capacity). It also claims that the “new” plan “has no impact on the City’s Debt Capacity Policies.” Note, the wording is that issuing the G.O. debt won’t affect the city’s “Debt Capacity Policies,” which is different than the debt having a legal effect on the city’s debt capacity by outside credit rating agencies (more on this in a few paragraphs).

CDA bonds rates are always higher because of the higher risk, and they also require something of value as collateral (property, for instance); G.O. bonds require zero collateral because the risk is offset by the city’s obligation to pay the debt (or tax its way out of it) or it will face a serious credit rating downgrade to borrow for future projects.

CAO Saunders and Deputy CAO for Economic and Community Development Sharon Ebert joined the Davenport chorus and both told City Council last week that even issuing $170 in general obligation debt would NOT count against the city’s debt capacity. However, just repeating that over and over does not make it so.

According to BizSense, Ebert emphasized that assuming the bond debt would not affect the city’s ability to issue bonds for other capital improvement projects such as schools.

This is much more cost-effective,” said Ebert, who also addressed the risk to the city should the project fail to produce the projected revenues.

There is risk; I don’t want to say that there isn’t any risk,” she said. “Taking this approach does require the city to put its full faith and credit behind the bond if the tax revenues don’t materialize as expected.

BizSense reported that CAO Saunders said

the approach toward the new stadium would not impact the city’s debt capacity and would free up nearly $24 million of debt capacity that had been programmed for the [expanded TIF district] infrastructure improvements. He described the approach as similar to how the city financed the Stone Brewing production facility, in which the debt has been offset by the company’s lease payments.

The only problem with that “analysis” is that it is not. The financing of Stone was done using general obligation bonds, but the lease Stone had with the EDA was enough to cover the debt service; however, it was still a risk if the company suddenly disappeared and no one stepped in to buy or lease a modern, fully functioning brewery (in the case of the stadium, there is no lease to cover the entire bond debt repayment).

An article by Michael Martz in the Times-Dispatch in October 2014 reported that the Stone bonds would carry the city’s moral obligation and Davenport recommended use of general obligation bonds as “the most efficient means of providing the desired lease terms” in the letter-of-intent between the city and Stone.

Martz wrote:

The financial adviser also raised the possibility that the debt for the project could be excluded from Richmond’s total debt capacity, based on Stone’s commitment to repay the debt through lease payments under financial policy guidelines that already are being revised.

Although this (general obligation) debt should not count against the city’s capacity from a policy perspective since it is being repaid from lease revenues, the credit rating agencies will still count it in their analysis because it is not funding an essential public project, Davenport states.

A year and a half later, however, Davenport admitted that the Stone debt did, in fact, count against the city’s debt capacity. In the document entitled “Playing the Economic Development Game under the New Realities,” Davenport presented the topic at the Virginia Government Finance Officers’ Association Spring Meeting in May 2016. The document reads [emphasis added]:

Davenport believes that the G.O. Bonds issued for the (Stone Brewing) Project should not have counted against the City’s capacity from a debt policy/capacity perspective since it was being repaid from a definable and known stream of lease revenues from day one.

However, the G.O. Bonds did count against the City’s legal debt limit and the Credit Rating Agencies did count it in their overall analysis because it is not funding an essential public project.

One can argue all day long if a baseball stadium is an “essential” public project or not. But, if issuing general obligation debt to build a school counts against the city’s debt limit (which it does and is undoubtedly an essential public project), then you can’t argue that issuing general obligation debt to build a baseball stadium doesn’t count against the city’s debt limit.

Back in January, Em Holter at the Times-Dispatch reported that the city is facing a crunch in its debt capacity to deliver things like schools and a new John Marshall Courthouse, which is no longer in compliance with state code. In the article, Chief Investment Debt Officer Michael Nguyen said a new courthouse would cost $300 million, (a price tag, strangely, that is three times as much as Loudoun County’s new courthouse) and might put the city in a bind because our policy is to only borrow 10% of what we collect in a fiscal year and making sure that 60% of any debt incurred is paid off within ten years.

“When the administration and the council decide to borrow funds, that impact is felt for the city and commits future administrations and future councils to spending priorities,” Nguyen said. “So one way to think about this is that we can take on a lot of debt, but the ultimate issue lies with can we afford to pay that now and in the future years to come. That affordability part is a decision that could squeeze out or crowd other spending priorities.”

The article noted that a $300 million project would have a drastic impact and require about a $19.5 million annual payment, so the stadium taking $170 million of that would also have a sizable impact — especially if we don’t have a schedule of when it will be paid back — which we don’t.

One of the missing pieces so far in the “new” stadium deal is that there is no agreed-upon lease with the Squirrels yet, though one is expected to be finalized in the $2.5-$3 million range annually. However, no one knows yet who is responsible for the annual cost of upkeep and maintenance of the stadium and who will pay when MLB comes back in ten years and requires more upgrades to meet their minimum standards.

But even with the Squirrels paying the most expensive lease in minor league baseball history (by far), that amount would come nowhere near meeting the amount to cover the total debt service for the bonds (like the Stone deal), which according to BizSense, is expected to be about $10 million annually. It is estimated that the infrastructure bond debt would total about $3 million per year and the roughly $7 million of stadium bond debt will have to be paid by incremental tax revenues from the surrounding development and other taxes generated within the Diamond District boundaries. The faster that gets developed and generates revenue, the more those revenues can pay the debt instead of the city’s general fund.

The problem with the estimated $10 million debt service number is that no one knows exactly what the debt service will be on an annual basis because so far there has been no debt schedule for the stadium or Diamond District infrastructure shared with Council or the public. It could be $8 million or it might be $12 million. No one knows for sure and there are no assurances in the agreements going before Council next week that protect the city in any fashion from becoming a cash register with endless payouts.

The city is writing a blank check and the details will be filled in later on the other side and can be written with little protection for the city since they are committing to cover all the debt no matter what happens. In most responsible localities, at the very least, a debt schedule would be a precondition to the approval of issuing such a large amount of debt, as would requirements of audited financial reporting, which revenues would be directed to the debt, etc.

The non-stadium development in the Diamond District is vital in order to pay the debt for the stadium. The city and developers and City Council and taxpayers should know how much revenue is needed and how fast and how much development will generate revenue to pay the debt — but so far, that’s not the case here (this will be addressed more in the next part of our series). The good news is that if any area can grow rapidly to begin generating revenue, it is the area around the stadium, which has seen meteoric and unbated growth for a decade with few signs of stopping anytime soon.

Whenever a development is backed unequivocally by the full faith and credit of the city, then everyone involved knows that no matter what happens with the development — stadium cost overruns, missed development targets, soil remediation, earthquakes, locusts, or the zombie apocalypse — the city will ultimately be on the hook for the debt and have to pick up the tab if any or all or it goes south.

However, without the Mayor or City Council pressing for more defined development timelines or assurances that the city can foreclose or retain clear claw-backs on the development if something goes amiss, then the city is about to rush headlong into a deal with potentially seismic long-term consequences.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.