House Speaker Paul Ryan savors his biggest legislative victory.

Faced with a chronically slow-growth economy, expanding deficits, mounting federal debt, and a looming funding crisis for the U.S. welfare state, Republican congressmen are, to borrow a football metaphor, throwing a hail Mary pass into the end zone in the desperate hope of scoring a winning touchdown. They are gambling that tax cuts combined with President Trump’s deregulation agenda will boost economic growth from roughly 2% per year to 3% or more, reducing the tax burden for millions of Americans, creating new jobs, boosting wages, and bending the curve on long-term deficit projections.

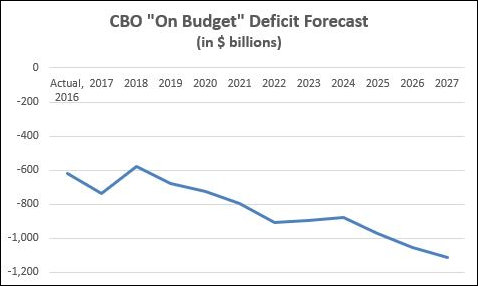

Convinced that the tax cuts will prove to be a disaster for everyone but the rich, Democrats and the mainstream media have subjected the tax plan to relentless, unremitting attacks. Viewed in terms of static economic analysis, we are told, the tax cuts will inflate federal deficits by a cumulative $1.5 trillion over the next ten years. Suddenly, deficits matter!

Republicans respond that measures in the bill — accelerating write-offs for business investment, encouraging the repatriation of hundreds of billions of dollars in corporate profits to the U.S., and making the corporate tax rate more competitive internationally — will stimulate economic growth. Unlike the Democrats, I think that much will prove to be true. My question is: Will faster economic growth generate enough new tax revenue to offset that $1.5 trillion? Longer term, will it avert Boomergeddon?

Let’s dig into the numbers. The Congressional Budget Office’s current 10-year budget forecast assumes a modest 2.1% annual growth rate over the next ten years, a slight uptick from the trend established during the Obama years. But economic growth has accelerated to roughly 3% in the past couple of quarters, and the Trump administration’s deregulation + tax cuts strategy could nudge it even higher. Let us assume for purposes of discussion that, thanks to the tax cuts, the U.S. can grow the economy at a sustainable rate of 3.1% annually. What does an extra percentage point in economic growth get us in deficit fighting?

Well, the latest CBO federal revenue forecast for the next ten years is $43 trillion. A 1% boost in federal revenues will yield $430 billion, not nearly enough to close the $1.5 trillion gap. The analysis gets a bit more complicated because economic growth and higher incomes push Americans into higher tax brackets while a roaring stock market generates massive capital gains. So a 1% increase in economic growth could produce more than a 1% increase in federal revenue. Let’s go for the gusto and double the growth-to-revenue ratio, assuming that federal taxes increase actually increase by $86 billion per year over current projections. That’s still doesn’t close the ten-year $1.5 trillion gap.

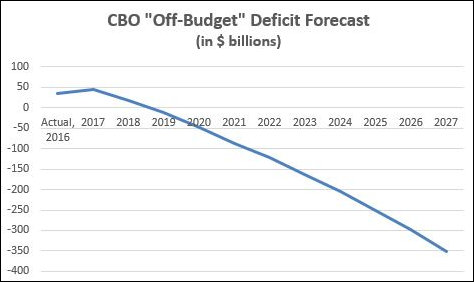

Could the economy grow much faster than 3.1% over the decade ahead? I’m skeptical. First, Baby Boomers are retiring in droves, and the working-age population is stagnating. A growing labor force supports economic growth; a stagnant labor force undermines it. Second, the Federal Reserve Board, intent upon unwinding the monetary stimulus of the Obama years, will continue to raise interest rates. It goes without saying that higher interest rates are a damper to economic growth.

In summary, in my untutored opinion, I think that the U.S. will see modestly faster economic growth over the next few years. The Dems have predicted economic Armageddon. They won’t get it. The lives of millions of Americans will improve… in the short run. But Republicans are deluding themselves if they think modestly faster economic growth will reduce the nation’s long-term structural budget deficit. Entitlement spending is still running out of control, and the nation still faces a hideously painful fiscal reckoning. Our 20-year future still looks like Boomergeddon.

Now that Democrats are close to parity with Republicans in the House of Delegates, there is renewed talk of Medicaid expansion in Virginia. Meanwhile, in Washington, President Trump and Republicans are pushing a tax-cut plan that would spur economic growth but, even with stronger growth, would increase deficits by $1.5 trillion over the next ten years. Nobody is talking about the $14.6 trillion national debt except as a cudgel against partisan foes. Even as Medicare, Disability, and Old Age and Survivors trust funds are projected to run out within a single generation, entitlement reform is not up for discussion.

Now that Democrats are close to parity with Republicans in the House of Delegates, there is renewed talk of Medicaid expansion in Virginia. Meanwhile, in Washington, President Trump and Republicans are pushing a tax-cut plan that would spur economic growth but, even with stronger growth, would increase deficits by $1.5 trillion over the next ten years. Nobody is talking about the $14.6 trillion national debt except as a cudgel against partisan foes. Even as Medicare, Disability, and Old Age and Survivors trust funds are projected to run out within a single generation, entitlement reform is not up for discussion.

S&P Global has warned that Illinois’ debt could be downgraded to junk bond status if the state doesn’t get its fiscal affairs in order. Paralyzed by partisan gridlock, the Prairie State hasn’t had a budget in two years. Since the Great Depression, no other state has gone for more than a year without a budget, reports the

S&P Global has warned that Illinois’ debt could be downgraded to junk bond status if the state doesn’t get its fiscal affairs in order. Paralyzed by partisan gridlock, the Prairie State hasn’t had a budget in two years. Since the Great Depression, no other state has gone for more than a year without a budget, reports the