Just a few years ago, Gov. Terry McAuliffe seemed to be a reasonable advocate of a healthy mix of energy sources. He boosted renewables and opposed offshore oil and gas drilling. He was suspicious of dangerous, dirty coal.

Then he started to change. During the campaign last year, he suddenly found offshore drilling OK, which got the green community worried. But there’s no doubt about his shifts with his wholehearted approval of the 550-mile Atlantic Coast Pipeline proposed by Duke Energy, Piedmont Natural Gas and AGL Resources, along with Richmond-based Dominion, one of McAuliffe’s biggest campaign donors.

The $5 billion Atlantic Coast Pipeline is part of a new phenomenon – bringing natural gas from the booming Marcellus Shale fields of Pennsylvania, Ohio and northern West Virginia towards busy utility markets in the Upper South states of Virginia, North Carolina and parts ones even farther south. Utilities like gas because it is cheap, easy to use, releases about half the carbon dioxide as coal, which is notorious for labor fatalities, disease, injuries and global warming.

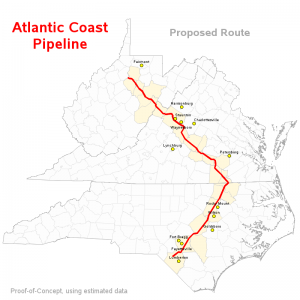

The Atlantic Coast Pipeline would originate at Clarksburg, W.Va. (one of my home towns) and shoot southeast over the Appalachians, reaching heights of 4,000 feet among rare mountain plants in the George Washington National Forest, and then scoot through Nelson, Buckingham Nottoway Counties to North Carolina. At the border, one leg would move east to Portsmouth and the Tidewater port complex perhaps for export (although no one has mentioned that yet). The main line would then jog into Carolina roughly following the path of Interstate 95.

It’s not the only pipeline McAuliffe likes. An even newer proposal is the Mountain Valley Pipeline that would originate in southern West Virginia and move south of Roanoke to Chatham County. It also faces strong local opposition.

The proposals have blindsided many in the environmental community who have shifted some of their efforts from opposing coal and mountaintop removal to going after hydraulic fracking which uses chemicals under high pressure and horizontal drilling to get previously inaccessible gas from shale formations. The Marcellus formation in Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio and West Virginia, the birthplace of the American oil and gas industry, has been a treasure trove of new gas.

The proposals have blindsided many in the environmental community who have shifted some of their efforts from opposing coal and mountaintop removal to going after hydraulic fracking which uses chemicals under high pressure and horizontal drilling to get previously inaccessible gas from shale formations. The Marcellus formation in Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio and West Virginia, the birthplace of the American oil and gas industry, has been a treasure trove of new gas.

The fracked gas boom has been a huge benefit to the U.S. economy. It is making the country energy independent and has jump started older industries in steel, pipe making and the like. By replacing coal, it is making coal’s contribution to the national energy mix drop from about 50 percent to less than 40 percent and is cutting carbon dioxide emissions that help make for climate change.

That at least, is what the industry proponents will tell you and much of it is accurate. But there are big problems with natural gas (I’ll get to the pipelines later). Here’s Bill McKibben, a Middlebury College professor and nationally known environmentalist writing in Mother Jones:

Methane—CH4—is a rarer gas, but it’s even more effective at trapping heat. And methane is another word for natural gas. So: When you frack, some of that gas leaks out into the atmosphere. If enough of it leaks out before you can get it to a power plant and burn it, then it’s no better, in climate terms, than burning coal. If enough of it leaks, America’s substitution of gas for coal is in fact not slowing global warming.

Howarth’s (He is a biogeochemist) question, then, was: How much methane does escape? ‘It’s a hard physical task to keep it from leaking—that was my starting point,’ he says. ‘Gas is inherently slippery stuff. I’ve done a lot of gas chromatography over the years, where we compress hydrogen and other gases to run the equipment, and it’s just plain impossible to suppress all the leaks. And my wife, who was the supervisor of our little town here, figured out that 20 percent of the town’s water was leaking away through various holes. It turns out that’s true of most towns. That’s because fluids are hard to keep under control, and gases are leakier than water by a large margin.

A recent Academy of Sciences report suggests that the problems from toxic chemicals used in fracking aren’t really that big a threat to drinking water. The larger problem is that the cement used as sealant up and down steel drilling pipes is prone to leaks. Something like it happened when cement on the ocean floor under the Deepwater Horizon rig in 2010 failed, creating an uncontrollable spurt of gas and crude oil from thousands of feet below in the Gulf of Mexico.

So, methane leaks may not make methane coal’s panacea after all. Another little noted problem is that the drilling boom involves ripping up tracts of mostly rural, hilly land. Residents find that the little dell next door has suddenly turned into a 24/7 industrial operation with loud diesel generators, flood lights and trucks that destroy and hog narrow roads.

A different form of this sudden change in landscape is inevitable with new pipelines. Dominion and other utilities will be able to survey one’s land without permission. They will be able to seize it under eminent domain if a sales price can’t be reached. And the construction will rip up sensitive ecosystems. According to the Virginia Sierra Club:

The pipeline path would cross eight Highland County mountain ridges at elevations of 3000 to 4200 feet: Tamarack Ridge, Red Oak Knob, Lantz Mountain, Monterey Mountain, Jack Mountain, Doe Hill, Bullpasture Mountain and Shenandoah Mountain. It’s not just the view shed that concerns Webb; he fears the resulting forest fragmentation caused by the construction of the pipeline could have adverse impacts on the flora and fauna of the region, including the loss of dependent species, the introduction of invasive species and the loss of habitat for sensitive species such as the Indiana bat and the Cow Knob salamander.

To be sure, there have been pipelines in Virginia before. The most significant is the Colonial Pipeline that links Gulf Coast gas fields with large metropolitan areas in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast. It followed what was then the major gas route – Louisiana to New Jersey. Colonial was built starting in the 1950s. That was just a little after World War II when German U-Boats plundered northeast-bound tanker traffic so severely that domestic energy supplies were in jeopardy.

There haven’t been that many problems with the Colonial Pipeline over the years but that doesn’t mean they can’t happen. I will never forget the summer of 1989 when I was finishing my first stint as Moscow bureau chief for BusinessWeek. The Russians didn’t take very good care of their pipelines and they have a lot of gas.

It just so happened that a pipeline in a narrow railroad passage was leaking near the industrial city of Ufa. Two passenger trains were approaching the gas-filled valley from either side. One carried hundreds of school children on their way to camp. The trains touched off an explosion so massive it was compared with a low yield nuclear weapon. Some 645 died, including school kids who were blown to bits.

I also remember that one way safety crews checked for leaks at pipelines during frigid Siberian winters. They’d fly in helicopters and shoot flares at what seemed to be clouds of gas. An explosion meant a leak.

Certainly American safety standard are better, but isn’t this all happening too fast? Dominion wants its pipeline in place by 2018. They want the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to fast track it. They are already running into strong local opposition in places such as Nelson County.

The Atlantic Coast Pipeline with without a doubt one of the biggest, costliest and far-reaching energy project the state has seen in years. But don’t forget how powerful small places can actually be.