by James A. Bacon

Apple, Google and other collosi of Silicon Valley are re-shaping the world with their technology but you could never imagine them as masters of innovation by viewing their corporate campuses. While the office interiors may be arrayed with java bars and collaborative workplaces to stimulate creativity, the building exteriors are for the most part bland steel-and-glass boxes of a type that can be found anywhere in the United States. Moreover, surrounded by parking lots and landscaping, the buildings are isolated — islands in a sea of mulch and asphalt. Creativity and interaction end at the front door. The streets, sidewalks and other pieces of the public realm are innovation dead zones.

That was the impression I gained from the Bacon family’s whirlwind tour of Silicon Valley earlier this week that took in the corporate headquarters not only of Apple and Google but Hewlett-Packard, Yahoo! and LinkedIn. Perhaps we arrived at the wrong time of year, the wrong time of the week or the wrong hour of the day but we saw almost nothing going on. Most of the street-level activity at Apple was generated by tourist traffic to the Apple store. The environs of the famed Googleplex were even more desolate.

I was expecting bustling outdoor scenes like those shown in the movie, “The Internship,” in which Owen Wilson and Vince Vaughn finagled their way into summer jobs at Google and into movie goers’ hearts. We didn’t see bupkis. I sneaked around the back of one of the buildings in the Googleplex and did discover an inviting patio with bright umbrellas but didn’t see anyone except a couple of maintenance guys standing around and shooting the breeze. As we drove around the Google corporate campus with its dozens of buildings, we did espy one multi-colored Google bike leaning against a wall and we did spot one fellow riding down the road, but we saw hardly anyone walking outside. Undoubtedly, billions of neurons were burning brightly inside Google’s buildings — but there was no sign of the company’s massive brainpower on display outside. It turns out that, according to CNN, much of the movie wasn’t filmed at Google at all — but the Georgia Institute of Technology campus in Atlanta!

The Google H.Q. is so low-key in appearance, we wondered if we had the right place. This is where Google Maps led us.

Who cares whether the innovation occurs inside or outside? Why mess with a proven formula? More to the point, what does a techno-tard like me have useful to say to the likes of Apple and Google, two of the greatest wealth creation machines in human history?

I didn’t visit Silicon Valley with the idea of lecturing the region’s political, business and civic leaders how to improve, which would be incredibly presumptuous on my part. I visited to learn what lessons other communities might learn. Scores of regions around the United States yearn to re-create some of the valley’s technology magic, and I worry they could draw the wrong conclusions. The one dimension of Silicon Valley that others can most readily replicate is its “suburban sprawl” pattern of development — and that would be the worst possible lesson to take away.

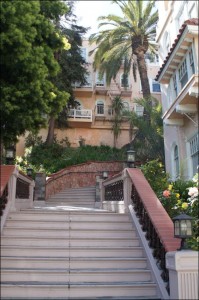

The parking lots outside Apple’s headquarters are beautifully landscaped but they wall off pedestrian access to the world outside.

I would humbly suggest that Silicon Valley has been insanely successful in spite of its dysfunctional human settlement patterns. Combine world-class research universities, the largest venture capital community in the world and an unparalleled workforce, then shake and stir. You’ll get technological innovation. Silicon Valley’s corporations can create a built environment that discourages interaction outside the firm and it doesn’t matter — the advantages of a Silicon Valley location far outweigh the drawbacks. But no one else has Silicon Valley’s potent mix of research universities, venture capitalists and the smartest engineers drawn from around the world. Other communities need every competitive advantage they can muster — and smarter land use patterns is one of them.

As Hans Johannson has argued in his book, “The Medici Effect,” innovation comes at the intersection — the intersection of different industries, disciplines, cultures or ways of thinking — that allow people to make unlikely combinations of ideas. Some places lend themselves to that kind of interaction, others don’t. Based on her experience living in Greenwich Village a generation ago, renowned urbanist Jane Jacobs brilliantly argued that sidewalks, small parks and mixed uses lent themselves to the kind of meetings and encounters, often serendipitous, where different perspectives and ideas can collide. To spawn entrepreneurship from the ground up, those are the kinds of neighborhoods and communities that aspiring tech centers should be creating.

The built environment of Silicon Valley is Northern Virginia with palm trees — predominantly single-family houses, strip malls and office parks. Thanks to municipal codes and NIMBYs, the region can increase density only sparingly, so it cannot grow “up” by building taller buildings. But wedged between the bay to the north and mountains to the south, it cannot grow “out” through additional sprawl. As a consequence, real estate prices are incredibly high. The cost of housing across the Valley and throughout the entire Bay area is consistently cited as one of the greatest hindrances to living there. The number of homeless in the San Jose metro region, according to the Wall Street Journal, numbers roughly 7,600. To adopt similar land use policies would suicidal for any other region.

Municipal leaders recognize these shortcomings and are attempting belatedly and with mixed results to deal with them. I will discuss two such initiatives in Sunnyvale, as time permits.

by James A. Bacon

by James A. Bacon