by James A. Bacon

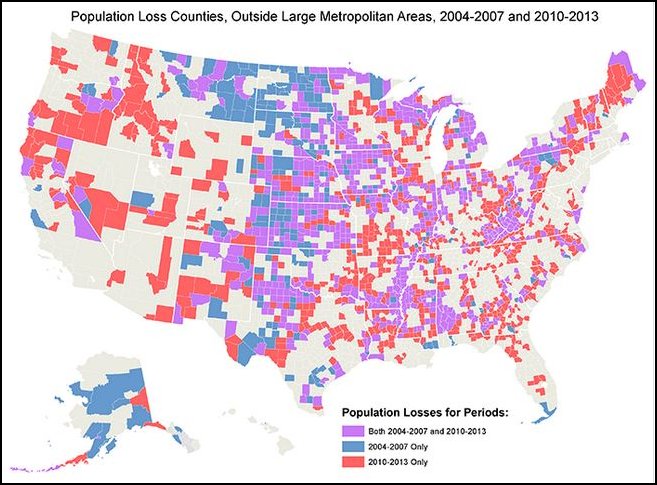

In theory the past decade should have been very good for America’s small towns and rural areas: The fracking revolution has created an energy boom in places as far flung as western Pennsylvania and North Dakota. High prices for agricultural commodities have propped up incomes across the grain belt. Yet, despite the strength of the natural resource economy, non-metropolitan populations are shrinking.

Summing up Bureau of Census data through 2013, the Brookings Institution concluded that, outside of energy boom towns and retirement magnets, the future does not look good for small town America. Communities outside of metropolitan statistical areas showed the third straight year of population loss in 2013. Small cities and towns dependent upon manufacturing have been particularly hard hit.

In this blog, I have frequently cited the work of urban geographers who explain that a knowledge-based economy favors large metropolitan regions with large labor markets of skilled and educated employees. Knowledge-intensive companies gravitate to regions where they can hire workers with the skills they need, and workers gravitate to regions where they can find employment. While this trend does not trump all other considerations — Detroit is a case in point — it is powerful. Only in unique circumstances — a university town, an energy boom town, a town blessed with extraordinary climate or beauty — can small towns fight the tide. Small towns dependent upon light manufacturing especially appear doomed to long-term decline.

In his recently published book, “The Economic Viability of Micropolitan America,” Gerald L. Gordon asks the question, can micropolitan areas (urban centers with populations between 10,000 and 50,000) survive? Gordon is best known in Virginia as CEO of the Fairfax County Economic Development Authority, one of the most respected and successful economic development enterprises in the country. But he also has an academic bent and when he’s not closing big deals like the relocation of Volkwagen USA and Intelsat to Fairfax County, he’s teaching economic development as an adjunct faculty member and doing his own research.

The latest book is one in a series aimed at extracting economic development lessons from communities large and small around the U.S. For this book, Gordon interviewed the mayors of 70 micropolitan communities, including two in Virginia: Danville and Martinsville. While small-town mayors maintain an up-beat outlook as their communities’ chief salesmen, the outlook Gordon describes is grim.

One rampant problem is the brain drain, the loss of residents with skills and education, to larger metropolitan areas that offer superior career prospects. The small towns’ problem is the inverse that of the major metros. Lacking a skilled and educated workforce makes it difficult to attract higher-quality employers; the lack of higher-quality employers makes it difficult to recruit or retain educated workers. Writes Gordon:

The loss of a primary employer means more than the loss of jobs and taxes. It can also mean the loss of the best of the workforce in the city as well as private support for organizations and causes throughout the community. This brain drain is an extremely serious for micropolitan cities.

That problem feeds another one: The erosion of the business tax base and the loss of higher-income individuals reduces the resources available to small towns and cities to make the investments in education and infrastructure they need to grow. “The ‘Catch-22’ is that the community then becomes less attractive to potential new residents and employers.

If there is a magic formula for success, Gordon didn’t find it. Indeed, his summary chapters are remarkably pessimistic — not for any apocalyptic language, which he studiously avoids, but for the simple paucity of plausible economic-development strategies beyond the well-worn ideas of diversifying the economy and revitalizing downtown.

That’s not to say that the future of micropolitan America is hopeless. There is a niche for people who prefer a slower-paced life in a tightly knit community where everyone knows and supports one another. For the most part, those people are retirees. I confess, I did not read all 70 of the community profiles, but I saw little discussion of what it takes to become a successful retirement community — something any region with access to beaches or mountains can reasonably aspire to.

There also is a niche for micropolitan areas on the periphery of large metros. Here in Virginia, small cities and towns in the Shenandoah Valley or along the Chesapeake Bay can cater to affluent residents of the Washington metropolitan area by creating a weekend-getaway economy of B&Bs, boutique stores and restaurants, local crafts, and activities geared to sailing (on the Chesapeake) or the mountains (Shenandoah). These regions can even recruit burned-out urban dwellers seeking a bucolic place to live while working as a consultant or telecommuter. A disproportionate number of these escapees wind up starting small businesses and becoming local employers. Unfortunately, to date, local economic developers have stuck with the industrial-recruitment strategy that bears less and less fruit.

Thirdly, micropolitan communities should consider the virtues of smart growth. All small towns — those in Virginia, at least — are mini replicas of metro Washington, Richmond and Hampton Roads in having allowed auto-centric growth to leak into surrounding counties even as the urban core struggles to maintain its population. The consequence of a dispersed population is that it becomes more expensive to provide citizens with infrastructure and public services than it need be, thus making it more difficult to maintain the quality of public services needed to attract new residents and businesses. (Every mayor of a small Virginia city should become a faithful reader of the Strong Towns blog based on the observations of Charles Marohn in Brainerd, Minn., who chronicles the foolhardy investment of scarce small-town resources in infrastructure projects that yield little value.)

Those small-bore ideas may be a big leap for someone like Gordon, whose cosmopolitan EDA maintains offices in Bangalore, Tel Aviv, Munich, London and Seoul among other places. But it’s a leap that the small-town mayors had better make. What they’re doing now isn’t working, and there is no reason to think that the economics of urban growth will change anytime soon. If small-town leaders need any further proof, they should read Gordon’s book and see what their peers are doing — or not doing.