Bird, the Uber of the electric scooter world, has deployed its first 50 scooters in Virginia — in Arlington County, to be specific. Arlington has no official policy regarding electric scooters, and Bird placed its black-and-white scooters without county permission. Whether that becomes a problem remains to be seen.

Bird, the Uber of the electric scooter world, has deployed its first 50 scooters in Virginia — in Arlington County, to be specific. Arlington has no official policy regarding electric scooters, and Bird placed its black-and-white scooters without county permission. Whether that becomes a problem remains to be seen.

“We will be having discussions with the county manager and the county attorney’s office on how to respond to Bird’s deployment of electric scooters in Arlington,” county spokesman Eric Balliet wrote in an email to the Washington Business Journal.

Bird, a California company that has raised $400 million in venture capital backing, has announced plans to expand into 50 new cities by the end of the year. The service works like this: Users download an app that identifies where unused scooters are located. Passengers ride the scooters wherever they want. Bird requires riders to wear helmets and stay off of sidewalks, but has no mechanism to enforce the requirements — a source of contention in some municipalities. At the end of the day, Bird picks up the scattered scooters and places in them locations where they are most likely to be used the next morning.

Bird’s Save Our Sidewalks pledge lays out the company’s thinking:

We’re witnessing the biggest revolution in transportation since the dawn of the Jet Age. From car ride-sharing to bike-sharing to autonomous and electric vehicles of all kinds, an explosion of innovation stands to transform the cities in which live, improve the environment, and help get us from Point A to Point B.

The sharing of bikes, e-bikes, e-scooters, and other short-range electric vehicles to solve the “last-mile” problem is an important part of this transformation. We have an unprecedented opportunity to reduce car trips –especially the roughly 40 percent of trips under two miles — thereby reducing traffic, congestion, and greenhouse gas emissions.

Smaller-than-automobile ride sharing is not without a downside, acknowledges Bird. “We have all seen the results of out-of-control deployment in China — huge piles of abandoned and broken bicycles, over-running sidewalks, turning parks into junkyards, and creating a new form of pollution,” states the Save Our Sidewalks pledge. To avoid having such things happen to the U.S., Bird vows:

- The company will retrieve all vehicles from city streets every night, inspect vehicles for maintenance and repairs, and re-position the entire fleet to where they scooters be wanted the next day.

- It will not increase the number of vehicles in a city unless they are being used on average at least three times per day (weather permitting). The company will remove underutilized vehicles, and it will share its data with cities for purposes of verification.

- Bird will remit $1 per vehicle per day to city governments so they can use the money to build more bike lanes and promote safe riding.

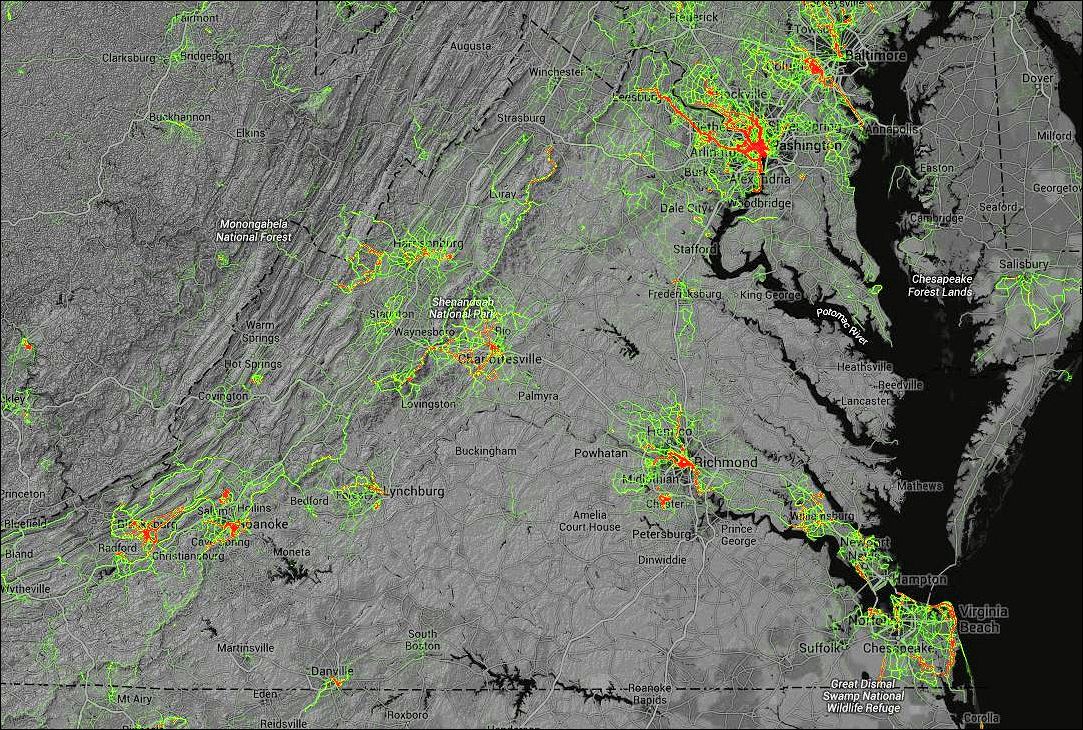

I have no idea how many people will cotton to the idea of riding electric scooters. But Bird is taking the financial risk, so I’m not worried about it. For the public, Bird’s approach sounds like a no-lose proposition — especially if scooter riders avail themselves of the ever-expanding bicycle infrastructure. Take Richmond for example. The city has been adding bicycle lanes (see Steve Haner’s recent post on the Franklin Street bike lanes), but it appears that the bike lanes are expanding faster than bicycle ridership. If bike lanes are under-utilized — and they seem way under-utilized to me — cities should be delighted to see them employed by a bicycle-compatible transportation mode like scooters.

Bird has only so much capital to deploy so many scooters in so many cities. I don’t know how it prioritizes markets for entry, but I presume that it would consider the percentage of young people, density, availability of mass transit, and the prevalence of bicycle lanes and other scooter-friendly infrastructure. Oh, yeah, and one more thing. An expressed desire by city officials to collaborate with the company — which Arlington, despite its preference for non-automobile transportation modes, has yet to provide. Richmond, Roanoke, and Norfolk should be stumbling over themselves to get in line for the next deployment of Bird scooters.

The more transportation choices the better.

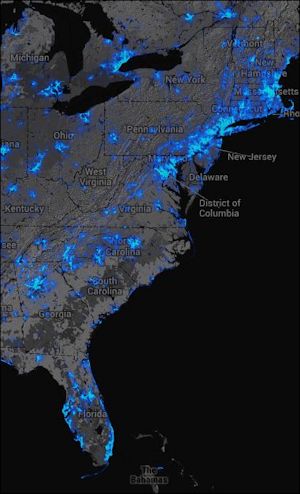

A higher altitude perspective gives quite a different picture. Virginia looks like a relative wasteland set between the Washington-Boston corridor and even the Raleigh-Atlanta corridor. The City of Richmond may have hosted the college cycling championship and is prepping to hold the world cycling championship but the metropolitan region barely registers on the heat map. Hampton Roads also makes a poor showing. (Hat tip:Streetsblog USA.) — JAB

A higher altitude perspective gives quite a different picture. Virginia looks like a relative wasteland set between the Washington-Boston corridor and even the Raleigh-Atlanta corridor. The City of Richmond may have hosted the college cycling championship and is prepping to hold the world cycling championship but the metropolitan region barely registers on the heat map. Hampton Roads also makes a poor showing. (Hat tip:Streetsblog USA.) — JAB