by James A. Bacon

Virginia transportation policy is driven overwhelmingly by a desire to mitigate transportation congestion and, to a lesser degree, to promote economic development. Rarely does traffic safety enter into the discussion of which transportation improvements we finance.

As evidence that congestion is one of the state’s foremost pressing concerns, elected officials can point to the annual Urban Mobility Report, which documents the cost of congestion in the nation’s metropolitan regions. In 2011, according to the 2013 report, congestion cost the nation $121 billion in lost time and wasted gasoline. But consider this: The economic cost of motor vehicle crashes amounted to $277 billion in 2010, finds a new study by the National Highway Transportation and Safety Administration, “Economic and Societal Impact of Motor Vehicle Crashes, 2010.” If you include the economic value of lives snuffed out — and why wouldn’t you, considering that the Urban Mobility Report counts the value of time lost sitting in congestion — the cost soars to $871 billion.

Think about that — the economic value of traffic accidents outweighs that of traffic congestion by four times but the overwhelming share of public transportation resources is funneled to relieving congestion. The question Virginians should ask themselves is this: Why are we spending billions of dollars to build new roads, highways and mass transit facilities and spending mere millions on making our transportation systems safer? By any rational measure, we have a twisted sense of priorities.

One can’t help but wonder why that is. The answer, of course, is political. I see two dimensions. First is popular perception. Nearly all of us experience the frustration and aggravation of traffic congestion to some degree. That means everyone can relate to the desire to tame congestion. By contrast, only a fraction of Virginians experience traffic accidents, and those incidents are by their nature episodic rather than chronic. Moreover, we tend to think of congestion as something that can be addressed by building more stuff, while we attribute traffic accidents to human frailty. It is less obvious to people how we can build safer roads that can protect us against, say, drunk drivers, distracted driving or road rage.

The second dimension is that traffic accident victims are not organized as a political force. By contrast, developers, construction contractors, labor unions, architects, engineers and an array of special interests stand to gain financially from expenditures on roads and mass transit justified on the grounds of traffic congestion. Through linkages to business organizations such as the chambers of commerce, these self-interested groups are able to mobilize the broader business community behind their initiatives.

Thus, the real estate/construction industry has donated $10.5 million in 2013-14 to Virginia political candidates, the largest of any group excepting the financial industry. Not a single traffic safety-related group appears in the Virginia Public Access Project’s list of miscellaneous, single-issue contributors. Environmental groups have contributed $4.8 million in 2013-14 but traffic safety ranks way down on their list of priorities compared to global warming, the Chesapeake Bay and uranium mining.

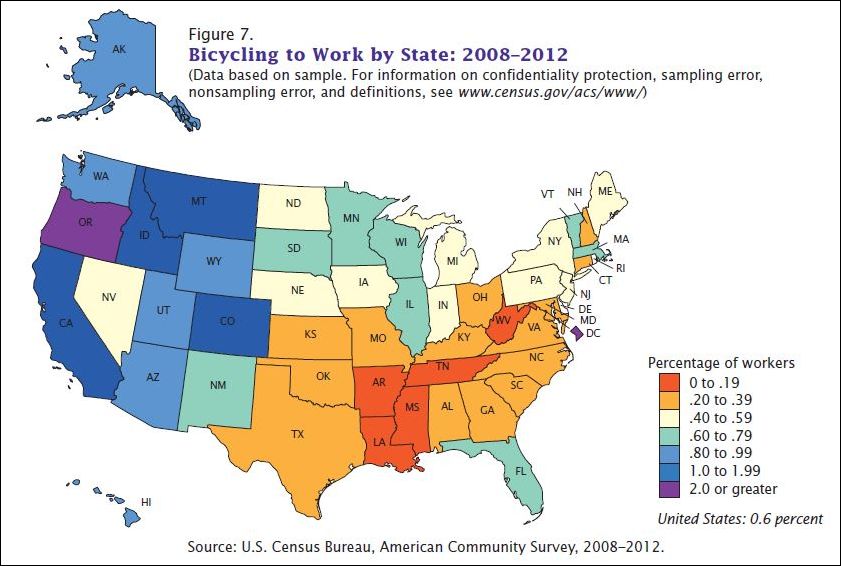

Perhaps another reason that safety warrants so little consideration in the Old Dominion is that the economic loss from traffic accidents in Virginia is lower than in most states. Traffic accidents cost $5.7 billion (in 2010 dollars), for an average cost of $713 per person or 1.6% of personal income. Only four other states (Hawaii, California, Minnesota, Oregon) experienced lower costs as a percentage of income. Be that as it may, the $5.7 billion toll is horrendously high compared to the level of public attention it receives.

As a practical matter, what could Virginia do to make streets and roads safer than they already are? First, take a look at where the traffic accidents occur. The NHTSA study indicates that intersection crashes resulted in 8,682 fatalities, 2.2 million injuries and 10 million damaged vehicles in 2010 — more than half of all crashes, a quarter of all fatalities, 50% of all economic costs and 45% of all societal harm.

I would hypothesize, subject to verification, that a disproportionate number of accidents take place in a relatively small sub-set of roads — typically commercial corridors that combine relatively high speeds (45 miles per hour) with lots of traffic signals, cut-throughs and driveways creating complex traffic patterns where cars collide at relatively high speeds. Many accidents could be remedied by better street design — turning our stroads (street-road hybrids) into Complete Streets that accommodate buses, pedestrians and cyclists intermingling at lower and safer speeds.

The other big killer category is “roadway departure crashes,” in which people run off the road. This accounted for 18,850 fatalities, 795,000 injuries and 2.4 million damaged vehicles, accounting for 26% of all economic costs and 35% of societal harm. Many of these accidents take place on windy, two-lane, undivided roads. Surely it would be possible to reduce the number of these accidents through such measures as road-straightening projects, wider shoulders and better marking in the most accident-prone stretches. Continue reading

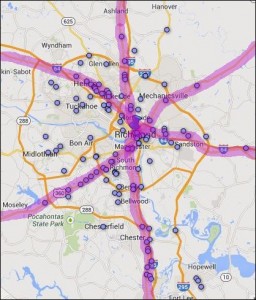

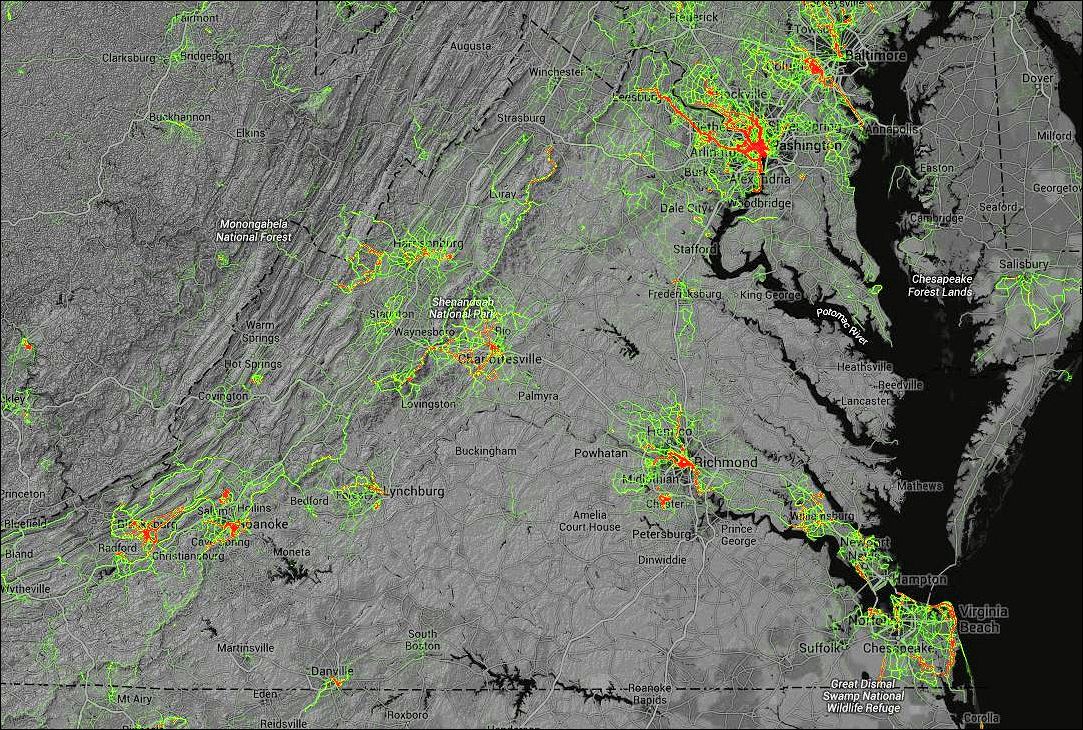

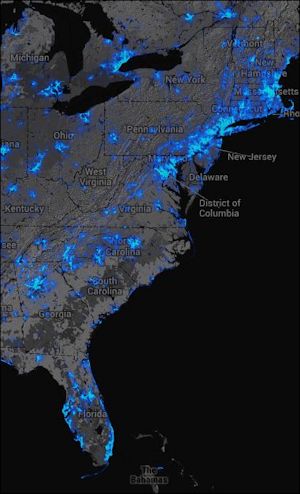

A higher altitude perspective gives quite a different picture. Virginia looks like a relative wasteland set between the Washington-Boston corridor and even the Raleigh-Atlanta corridor. The City of Richmond may have hosted the college cycling championship and is prepping to hold the world cycling championship but the metropolitan region barely registers on the heat map. Hampton Roads also makes a poor showing. (Hat tip:Streetsblog USA.) — JAB

A higher altitude perspective gives quite a different picture. Virginia looks like a relative wasteland set between the Washington-Boston corridor and even the Raleigh-Atlanta corridor. The City of Richmond may have hosted the college cycling championship and is prepping to hold the world cycling championship but the metropolitan region barely registers on the heat map. Hampton Roads also makes a poor showing. (Hat tip:Streetsblog USA.) — JAB