On January 29, the Richmond Times-Dispatch published an op-ed written by the patrons of HB319 and SB616 (The Virginia Literacy Acts). In this article, the legislators wrote that we must implement strategies adopted by other states if we wish to improve the reading abilities of our students.

While there is always room for improvement, one should always consult the data to determine to what degree our process should change in order to realize that improvement. If you’re at the bottom of the heap, you probably should change your approach dramatically. If you’re one of the top performers, maybe subtle tweaks are the more reasonable approach.

Consult the Data!

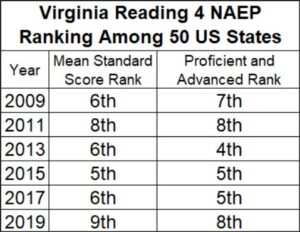

When it comes to early elementary reading, the most relevant dataset we have to compare our performance in Virginia to those of other states is the Reading 4 NAEP test. When we consider our results relative to the other 49 states, it appears that Virginia as a whole has performed admirably. Given that Virginia has achieved near the top very consistently, it is not apparent that we should make radical changes to our statewide reading program. Continue reading