Coal ash pit at the Chesapeake Energy Center

Meeting EPA deadlines constrains Dominion’s options for disposing of coal ash at four of its power stations.

Under Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) rules published in 2014, Dominion Virginia Energy must find a way to safely dispose of nearly 30 million tons of coal ash within 15 years. After intense controversy over how best to proceed, the General Assembly ordered Dominion to conduct a detailed study of the alternatives. That Dominion-commissioned study, written by engineering firm AECOM, was published in November.

Not surprisingly, given that Dominion has been locked in a running battle with environmentalists and community activists over coal ash disposal for about two years now, the study has settled nothing. On the one hand, AECOM affirmed that Dominion’s original plan — burying and capping the coal ash on-site — makes the most sense. On the other, the utility’s foes have attacked the study as inadequate on multiple grounds. The General Assembly will take up the issue in the 2018 session with few definitive answers.

Despite the seeming inability of the opposing sides to agree on anything, the AECOM study does illuminate the controversy. While Dominion foes criticize parts of the report, they are silent on others. Silence can be interpreted as tacit acceptance of some conclusions, or at least an unwillingness to contest them. For example, foes had long argued that the utility should transport the coal ash by truck or rail to lined landfills. AECOM contends that such a remedy would add billions of dollars to the cost of ash disposal. Since publication of the study, critics have dropped that line of attack and focused instead on the need to recycle the ash into concrete, bricks, and pavers — an approach that in theory could reduce the volume to be disposed of by half.

For decades, Dominion and other electric utilities had stored combustion residue from their coal-fired power plants in large pits on-site. Massive spills of coal ash into public waters, first in Tennessee and then in North Carolina, prompted the EPA to enact stricter standards for the storage of the material. A primary goal was to prevent another calamitous spill.

EPA regulations give electric companies five years plus two five-year extensions — a maximum of 15 years — to comply. Reacting quickly to the coal ash rules, Dominion proposed de-watering the ponds, consolidating the ash from separate ponds into one pit at each power station, and then capping the pits with a thick synthetic liner to prevent rain water from percolating through and picking up contaminants along the way. Arguing that Dominion’s plan would not prevent groundwater from migrating through the pits, environmental and activist groups insisted that Dominion dispose of the ash in landfills sealed from the groundwater and/or recycle the material into cement and other products.

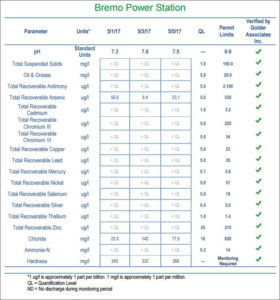

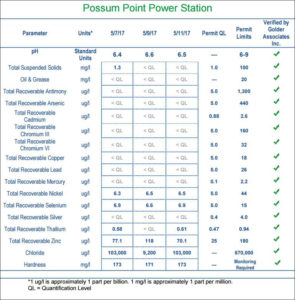

Under orders from the General Assembly, Dominion hired AECOM to study the alternatives. AECOM contends that the on-site impoundments will limit the long-term risk of contaminating groundwater and will withstand everything from flooding and storm surges to hurricanes and earthquakes. The engineering firm found that the so-called closure-in-place option cost far less than transporting the material to landfills. And in a site-by site analysis of four Dominion power stations — Chesapeake, Bremo, Possum Point, and Chesterfield — it concluded that recycling coal ash into concrete, bricks and pavers would lengthen the process of cleaning up the ash by many years.

Environmental groups have been highly critical of the study on two broad grounds. They say the AECOM report failed to address the disposal of more than two million tons of coal ash at the Chesapeake facility. And they contend that the engineering study gave short shrift to the option of reducing the volume of coal ash at Bremo, Possum Point, and Chesterfield.

The Chesapeake Power Station

According to the AECOM report, the cost of removing 60,000 tons of material from a pit at the Chesapeake facility designated the “Bottom Ash Pond” is paltry compared to that of the other power stations. Alternatives range in cost from $10.6 million to $13.3 million, although as much as $161 million might be needed to pay for corrective measures where contaminants have leaked into surrounding waters. Dominion, says the report, has committed to recycling and removing the material from the Bottom Ash Pond.

However, the AECOM report does not address disposal of coal ash contained in the far larger pit known as the “Historic Pond.” In a statement posted on its website December 15, the Southern Environmental Law Center made the following retort to the AECOM study:

In a glaring omission, Dominion Energy’s recent coal ash assessment fails to include any information about the large, unlined coal ash ponds leaking arsenic at its Chesapeake Energy Center, contrary to the requirements of the new Virginia law passed earlier this year. Senate Bill 1398 requires Dominion to assess and evaluate its coal ash facilities to provide information to the public, legislators, and regulators about how best to close the sites. But Dominion ignored the 2.1 million tons of coal ash in the unlined surface impoundment at Chesapeake Energy Center known as the “Historic Pond,” which contains roughly two-thirds of the ash at the site.

“This is clearly an attempt by Dominion to ignore the problem with its unlined coal ash ponds,” said Senior Attorney Deborah Murray in a letter to the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality. “We can’t pretend this ash does not exist. There is no legitimate reason for Dominion to have excluded this pond from its assessment, and the Department of Environmental Quality should require Dominion to remedy this omission immediately.”

Portions of the coal ash in the historic pond lie six feet below sea level, where it is saturated by groundwater and prone to releasing potentially toxic chemical compounds. “Dominion may not pick and choose the laws with which it will comply,” added SELC attorney Nate Benforado.

The SELC statement refers to a July ruling in which U.S. District Court Judge John Gibney found that contaminants from coal ash at Chesapeake were leaking into the Elizabeth River. According to Dominion spokesman Rob Richardson, Gibney ordered Dominion to conduct water, sediment and biological monitoring around the Chesapeake Energy Center, and also to submit by March 2018 a revised solid waste permit for the removal of an additional three million tons of coal ash at the Historic Ash Pond.

Dominion is not ignoring the wishes of the General Assembly by refusing to address those three million tons in the AECOM study, says Richardson. The Historic Ash Pond was closed nearly three decades ago, which means it is not subject to regulation under the EPA’s coal ash rules. Although Gibney found in March that traces of potentially toxic compounds had leaked into the river, the volume was so minute that there was no evidence of harm to human health.

Rather than compel Dominion to remove the coal ash, Gibney ordered the utility to propose corrective measures in an application for a solid waste permit. His ruling commanded Dominion and the Sierra Club Virginia Chapter to submit a “detailed remedial plan” that states, among other things, the timing of Dominion’s application for a permit. The Sierra Club and Dominion submitted that plan in July outlining extensive monitoring of the waters and wildlife around the Chesapeake facility, and Dominion has begun collecting the data.

The ultimate remedy at Chesapeake will be determined by Judge Gibney, not the Department of Environmental Quality, says Richardson. Therefore, the coal ash in the Historic Ash Pond needs to be considered separately from the coal ash subject to the Department of Environmental Quality.

Bremo, Chesterfield and Possum Point

While Gibney wrestles with how to dispose of coal ash at Chesapeake, the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) is charged with determining what to do with the much larger volumes of coal ash at Bremo, Possum Point and Chesterfield. Those power stations are storing 6.2 million tons, 4.0 million tons, and 14.9 million tons respectively. The AECOM study examines several approaches.

Closure in place. The low cost solution at each site is “closure in place” — consolidating the coal ash from multiple ponds into a pit, capping the pit with an 18-inch synthetic cover, adding a six-inch layer of soil, monitoring the groundwater, and taking “corrective measures” if groundwater toxins surpass allowable levels. The combined cost would run between $480 million and $1.7 billion for the three power stations, AECOM estimates. The main variable is how much money the company will have to spend on mitigation. AECOM’s low-cost plan would take three to five years to execute, well within the time frame mandated by EPA regulations.

While capping the coal pits would prevent rainwater from percolating through to the water table and picking up contaminants along the way, Dominion critics contend that closure-in-place would allow groundwater to migrate through lower levels of the ash pits. They want Dominion to remove the material to landfills with lined pits, sealing off the coal ash from any chance of groundwater contamination, as electric utilities in North Carolina and South Carolina are doing at some of their power stations in low-elevation areas.

Truck and rail. Trucking coal ash in 18- to 22-ton-capacity dump trucks to landfills miles distant from the power stations would require literally hundreds of thousands of trips on narrow roads, subjecting residential neighborhoods to traffic disruption, dust, truck emissions, and potential spills. In the case of the Possum Point station, AECOM assumes that 150 truckloads could be loaded daily, equating to a loaded truck leaving the site every three minutes, eight hours a day, five days per week. That process would take years longer than the closure-in-place alternative: nine years for Possum Point, 13 years for Bremo, and 29 years for Chesterfield. Dominion would be unable to meet the 15-year EPA deadline (which includes two five-year extensions) at Chesterfield. And the cost would approach $4.5 billion, making it billions of dollars more expensive than closure in place.

AECOM also examined the scenario of removing the coal ash by rail. That alternative was even more problematic, requiring added expense and time to build rail-loading facilities at the power stations. AECOM estimated a total cost of $7.3 billion, and the length of time to remove the coal ash as nine years for Possum Point, 13 years for Bremo, and 24 years for Chesterfield. The firm also looked at removing the coal ash by barge, but found that approach only remotely practical at Possum Point, and even there, it would cost $1.7 billion, far more than the truck and rail options for that facility.

Regional landfill. AECOM explored a fourth alternative: building a regional landfill from scratch. By reducing the distances that trucks have to travel, the regional approach would cost somewhat less than hauling the coal ash to private landfills: about $4.15 billion. But buying the land, getting the permitting and preparing the landfill would add six years to the disposal process, 21 years in all, during which the ash ponds would remain open.

From Ponds to Concrete

Coal ash is widely used in the United States as a supplement adding strength and durability to concrete and in making bricks and pavers. Recycling is regarded as environmentally benign because it encapsulates the material in a matrix that will not dissolve or release the potentially toxic heavy-metal compounds commonly found in ash.

Utilities in North Carolina and South Carolina have recycled coal combustion residue for years, and now they are ramping up their commitment in order to work down their own coal ash stockpiles. Environmentalists have suggested that Dominion consider recycling coal ash for the same reason: to cut disposal costs by reducing the volume of material to bury.

Coal ash comes in different varieties, and it often must be treated, a process referred to as beneficiation, to alter its chemical properties before it can be mixed with cement or used in other applications. At present Virginia has no beneficiation facilities. But several companies that conduct beneficiation in other states are eager to do business with Dominion.

University of New Hampshire professors Kevin Gardner and Scott Greenwood, engaged by SELC to study the coal ash issue, estimated that sufficient demand exists in Virginia for Dominion to recycle 16 million tons, more than half of its coal ash. In their report, “Beneficial Reuse of Coal Ash from Dominion Energy Coal Ash Sites,” They write:

Nationwide, coal ash is used in 75% of all concrete used for transportation projects, significantly reducing project costs. The Virginia Department of Transportation estimates that fly ash is used in 60% to 70% of all concrete used in transportation projects in the state, all of which, to the best of our knowledge, is currently fully sourced outside of the state due to the lack of beneficiation facilities operating in Virginia.

As an example of what beneficiation can accomplish, Gardner and Greenwood pointed to a beneficiation facility at the R. Paul Smith Power Plant in Maryland, which has removed 1.5 million tons from the power plant’s coal-ash landfill. The ash is expected to be mined out by 2020, allowing the area to be regraded, vegetated and closed, thus eliminating any remaining environmental risks. “As mining nears an end,” notes the report, “cement manufacturers are actively seeking similar stockpiles for continued reuse in the future.”

The economics of recycling can vary according to the properties of the coal ash and specific conditions at each power station, such as the volume to be recycled, local demand for the recycled material, and the cost of transporting the refined product to customers. None of these are insuperable barriers, says the Gardner-Greenwood report.

Representatives from the concrete industry have stated the need for high quality ash sources in the Virginia region and have indicated a willingness to set up long-term contracts for ash suppliers. Success in the mining and beneficiation of legacy ash in South Carolina has spurred the planning and planned groundbreaking for multiple new beneficiation plants in North Carolina in 2018, demonstrating economic viability. This combination of available technology, vendors with experience, a strong market and economic feasibility together make it clear the beneficial use of legacy ash from the Dominion Energy sites is possible, feasible, and given the environmental benefits, an overall preferred approach.

Not so Fast…

AECOM studied the feasibility of building coal-ash processing facilities at Bremo, Possum Point, and Chesterfield, as well as building a regional processing facility at Chesterfield. According to its calculations, costs would range as follows:

Bremo — $96 to $217 per ton

Chesterfield — $1oo to $285 per ton

Possum Point — $118 to $225

By contrast, contends AECOM, fly ash is selling on average for $30 to $60 per, on top of which Dominion would have to pay $7 to $33 per ton for transportation. In sum, the cost of beneficiation ranges from 1.5 times to nearly 5 times the market price for the ash, making it a major money loser in Virgina. Moreover, says AECOM, there is wide variability in the market, so demand for beneficiation cannot be accurately estimated. And the volume of coal ash entering the Virginia-Maryland-D.C.-North Carolina market is projected to exceed supply by 2019 as North Carolina utilities begin pushing more recycled material onto the market. Added volume from Dominion would create an even greater imbalance and depress prices.

If the decision were made to proceed with beneficiation, AECOM says, Dominion would need to conduct detailed cost and marketability discussions with beneficiation vendors to nail down firm commitments on processing rates and costs.

Coal Ash into Bricks

In a letter written to Dominion, Belden-Eco Products (BEP), developer of a process for converting fly ash (coal ash emanating from a smokestack) into bricks and pavers, corrects what President Robert W. Ittman terms “critical errors or misconceptions” in the AECOM study.

BEP’s patented process creates a superior ceramic brick that could be sold profitably into the $3.5 billion-a-year brick and paver market. The company asserts that its solution — building its facility close to Dominion’s ash ponds and shipping its products to market by rail or barge — would cost less than either landfilling or cap-in-place. The company says that it can generate far more than the $30 to $60 estimated by AECOM from a ton of fly ash — more like $119 to $214 per ton.

“BEP’s bricks would generate a positive income for Dominion of $1 to $55 per ton of fly ash over the course of the project,” states the letter. Partnering with BEP would generate $10 million in Net Present Value for Dominion over the life of the plant, a 7% internal rate of return.

However, the BEP letter does not address a critical issue raised in the AECOM study. AECOM estimated that installing a brick plant with a throughput of 300,000 to 550,000 tons per year — similar to the 500,000 figure cited in the BEP letter — it would take 30 to 53 years to excavate the coal ash ponds at Chesterfield. Dominion is required to devise a solution that removes the ash within 15 years.

Conclusions

A key factor driving Dominion’s decision to bury the coal ash in place is the necessity of finishing the clean-up within 15 years. Solutions that require making big capital investments with long permitting and construction lead-times won’t accomplish that aim. As a legal matter, Dominion must comply with the rules established by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and administered by Virginia’s Department of Environmental Quality. The point of the regulations, after all, is to prevent another coal ash spill that could result in environmental damage on a scale far more calamitous than the slow leaking of contamination through groundwater migrating through the coal ash ponds.

While recycling may not be a viable option at Dominion’s Chesterfield plant, it might work elsewhere. The AECOM study indicates that it would take only 11 to 17 years to excavate the ash pond at Possum Point using the Belden technology, and even fewer years using other technologies. Perhaps different solutions for each of Dominion’s four power stations could be cobbled together that recycles some of the coal ash, caps some in place, and trucks some to landfills off-site. Such a variegated solution would not be entirely satisfying to either Dominion or its foes, but it could reduce the potential environmental hazards without running up the tab by billions of dollars.