by James A. Bacon

There is a particular intersection near where I live in Henrico County — Patterson Avenue and Parham Road — that gets really jammed up during rush hour and sets my teeth to grinding. I hate it. I curse it. I give its traffic signals the finger. (Yes, I do have incipient road rage issues.) But I suppose I really have no grounds to complain. According to Wendell Cox, writing in New Geography, Richmond is the least congested of the nation’s 50 largest metropolitan areas. No one else comes close.

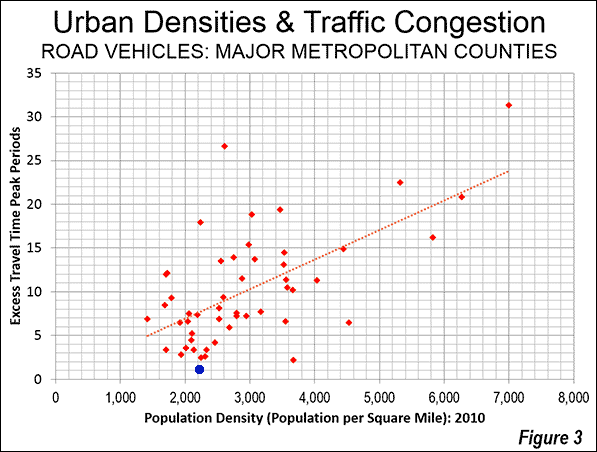

Cox derived his ranking from a composite of three major traffic congestion indexes: INRIX, Tom Tom and the Urban Mobility Report. One thrust of his blog post is to argue that traffic congestion is correlated with density: The greater the density of a metropolitan region, the greater the traffic congestion.

I can’t argue with Cox on this. There is a correlation between density and congestion. And Richmond (the blue dot) is a case in point. We have a relatively low-density metro. He acknowledges that other factors affect congestion as well. One of them, which he does not mention, is simply the size of the metro region. The most congested metros tend to be the largest.

Cox advances yet another explanation: the unwillingness or inability of congested metros to add new transportation highway capacity. Unlike my Smart Growth colleagues, I agree that it is theoretically possible for a region to build its way out of congestion. Theoretically. If money were no object. If Martians came along and beamed down billions of dollars in gold ingots. Of course, in the real world, money is always an issue. My argument is that building highways willy nilly is fiscally unsustainable. If the people who used those roads and highways actually had to pay for them through tolls, not many projects would get built. People always want new roads if someone else will pay for them. If they have to pay themselves, not so much. They’ll find better things to do with their money.

The same holds true of mass transit. People are happy to build new heavy rail, light rail and street cars if they can find someone else to subsidize them. If riders had to pay the full freight, none of them would get built.

The fact is, we subsidize the construction of more transportation capacity than we really need. We hate congestion but we hate it less than paying our fair share of what it costs to make the congestion go away. At some point, the congestion crisis will get so intense that people will be willing to pay out of their own pocket — in other words, when they’re willing to pay the tolls and/or fares — what it takes to build and operate the new capacity. That’s the point at which we should expand the system, not before.

By the way, the Washington metro region is No. 7 on Cox’s composite list of most congested metros, and Hampton Roads is No. 24.

An aside. Cox makes an interesting argument that less congestion offers a competitive economic advantage. “Because traffic congestion increases travel times, it necessarily reduces the share of a metropolitan area’s (labor market) jobs that can be reached by the average employee. A considerable body of research associates greater access (measured in time) with improved economic performance and job creation.” Sounds great. Here in Richmond, we’re waiting…