Richard Florida, who gained renown 15 years ago with his book, “The Rise of the Creative Class,” is a progenitor of big ideas exploring the nexus of urbanism, innovation and prosperity, and he’s back with another book and another big idea. Having documented in previous works that a handful of “superstar cities” are sucking up the lion’s share of artistic, scientific, and entrepreneurial talent and creating a wildly disproportionate share of global wealth, he delves into the dark side of urban prosperity. The title of the new book lays out his thesis succinctly: “The New Urban Crisis: How Our Cities Are Increasing Inequality, Deepening Segregation, and Failing the Middle Class—and What We Can do About It.”

Richard Florida, who gained renown 15 years ago with his book, “The Rise of the Creative Class,” is a progenitor of big ideas exploring the nexus of urbanism, innovation and prosperity, and he’s back with another book and another big idea. Having documented in previous works that a handful of “superstar cities” are sucking up the lion’s share of artistic, scientific, and entrepreneurial talent and creating a wildly disproportionate share of global wealth, he delves into the dark side of urban prosperity. The title of the new book lays out his thesis succinctly: “The New Urban Crisis: How Our Cities Are Increasing Inequality, Deepening Segregation, and Failing the Middle Class—and What We Can do About It.”

The “clustering” effect – capital, corporations and talent migrating to large metro regions with deep labor markets – creates a huge economic advantage for the world’s biggest metros, and an economic advantage for dense urban centers within those metros. As the creative class grows in wealth and power, there ensues a competition for prime urban space. Prosperous inhabitants bid up the price of housing, while NIMBYs inhibit the development of new units. Soaring housing prices drive out the working and middle classes, and push the poor into enclaves segregated by income, race, and education.

The result is “winner-take-all urbanism,” says Florida. “The talented and advantaged cluster and colonize a small, select group of superstar cities, leaving everybody and everywhere else behind.” This baleful trend, he describes as the “New Urban Crisis.”

As with all of Florida’s books, “The New Urban Crisis” has much to recommend it. Florida is very good at descriptive analysis – showing what is going on. It is impossible to finish this book without agreeing with his conclusion that a handful of highly innovative supercities are more prosperous than others, that the combination of increasing demand and constricted supply are increasing the cost of housing, and that housing soaring prices in these metros are displacing the poor and middle class. Florida will convince you that prosperous cities are becoming more unequal, not less, and that the pervasive pattern of the past half century – prosperous suburbs and decaying urban cores – is being replaced by a patchwork pattern of highly affluent neighborhoods intermixed with neighborhoods of concentrated poor in both urban cores and suburbs.

Florida is far less persuasive with his prescriptive analysis. As a political liberal, he agonizes over the growing inequality within metro areas, particularly the impact on poor African-Americans. Despite the promise of the book sub-title, he devotes little attention to how metros fail the middle class. Hispanics are strangely absent from the discussion. As for whites in rural/small town America, he evinces no concern whatsoever.

As a liberal, Florida remains sublimely confident that government is the solution to what ails the U.S. He is realistic enough to acknowledge that the New Deal/Great Society paradigm is getting long in the tooth, and that America needs to realign resources to reflect 21st-century realities. He also regards the thicket of NIMBY-empowering zoning regulations and building codes as a prime cause of rising housing prices and income segregation, and argues that they need to be scaled back. But whether he’s writing about the minimum wage, mass transit and inter-city rail, and the scourge of poverty, his confidence in the beneficent power of government never flags.

In previous books, Florida attributed the success of large metropolitan areas in large part to three factors – talent, technology and tolerance. By tolerance, he means acceptance of cultural and ethnic diversity: gays, bohemians, and racial, religious and cultural minorities. In a North American context, he is undoubtedly right: Open societies do foster creativity and innovation. (I’m not sure how well his paradigm applies to Singapore, Seoul, Tokyo or cities in ethnically homogeneous countries like Sweden and Finland, but that’s an issue for another time.)

He views Republicans as retrogrades, and regards the election of Donald Trump as an unmitigated disaster. “Summoning up the political will to face up to the New Urban Crisis will be no easy thing,” he says. “And it will be ever more difficult with Donald Trump as president and the Republicans in control of both houses of Congress.”

Yet he is strangely incurious about one of his own findings: The more politically liberal the city, the greater the inequality. At least he acknowledges the phenomenon, even if he explains it away:

Our most liberal cities number among the most unequal. …. Across the United States, inequality is not just a little higher, but substantially higher, in liberal areas than in more conservative ones. … My own analysis of all 350-plus US metros found wage inequality to be positively correlated with political liberalism and negatively associated with political conservatism.

Florida never entertains the possibility that liberalism causes poverty and inequality. “Of course, inequality is not a direct product of liberal political views,” he says. “Rather, liberalism and inequality are simply both attributes of large, dense, knowledge-based metros.”

An alternative narrative would suggest that inequality arises from the juxtaposition of massive wealth creation of new industries with tragi-comic ineptitude of big-city administrations, mostly Democratic and mostly liberal. “Blue” cities are more prone to over-spending and fiscal crises. (The situation in blue-state Illinois has deteriorated to the point, we read in the news today, that the PowerBall and MegaMillion lotteries are dropping the state as a client!) Blue cities have larger under-funded pension liabilities, their taxes are more punitive, their inner-city schools are worse, their murder rates are higher, and unemployment is more chronic – all of this despite the immense advantages conferred by the presence of greater wealth to tax.

A core argument of “The New Urban Crisis” is that high housing prices are driving inequality and income segregation. Florida alludes to the work of so-called market urbanists who argue that eliminating restrictive zoning and building codes will allow developers to build as needed. “They make an important point: zoning and building codes do need to be liberalized and modernized,” he concedes. “We can no longer allow NIMBYs and New Urban Luddites to stand in the way of the dense, clustered development our cities and our economy need.”

While deregulation will help by building more housing and increasing density, he adds, the high cost of land combined with the high cost of high-rise construction will limit new construction to expensive office towers and will not create affordable housing. As evidence, he points to Houston, one of the few large metros in the U.S. where developers “can build what and where they want.” While Houston housing is more affordable than New York’s, L.A.’s or San Francisco’s, he says, it is “rather expensive” compared to that of most other metros, and the metro ranks high in his inequality and segregation indices.

I’ve never found persuasive the argument persuasive the argument that building luxury towers instead of workforce housing leads to higher housing prices for the poor. If the super-rich occupy the luxury towers, they relinquish the slightly less luxurious/preferable accommodations where they once dwelled. The merely rich move in, in turn creating vacancies in their less opulent quarters, which in turn creates openings for the merely affluent, and so on down the line. Unless Latin industrialists and Russian oligarchs are buying up all the luxury tower units as a hedge, new luxury housing eventually exerts downward pressure on housing prices down the line.

Edward Banfield described the economic logic in his classic, “The Unheavenly City.” Writing in 1968 at the height of white flight and the original urban crisis, the urban sociologist foretold the trends that Florida describes in “The New Urban Crisis.”

If present trends continue, thee will not only be more people in the cities in the next two or three decades, but a higher proportion of them will be well-off. … In this very affluent society, housing probably will be discarded at an ever faster rate than now, and the demand for living space will probably be greater. In the future, then, the process of turnover is likely to give more and better housing bargains to the not well-off, encouraging them to move even farther outward and thus eventually emptying the central city and bringing “blight” to the suburbs that were new a decade or two ago.

Eventually land in the suburbs would be worth more than land in the central city, Banfield predicted. “When this time comes, the direction of metropolitan growth will reverse itself: the well-off will move from the suburbs to the cities, probably causing editorial writers to deplore the ‘flight to the central city’ and politicians to call for government programs to check it by redevelopment the suburbs.”

Lo and behold, 40 years later, Florida describes a “suburban crisis” of flight from cheap-to-build but expensive-to-maintain suburban sprawl back into the city. At least he avoids the trap of calling for government programs to redevelop the suburbs.

Banfield didn’t foresee everything – he did not predict the growing preference for walkable, mixed-use communities in denser settings. But he understood basic economics: As the wealthy migrate to the most luxurious housing, the poor migrate to the least desirable and cheapest housing. At this stage in urban evolution, that means the poor are moving into the aging, 50s- and 60s-era ranch-style tract houses of the inner suburbs that no one else wants. That’s the affordable housing that Florida yearns for, but he does not see it for what it is.

There’s nothing that liberals love more than a good social crisis – it gives them meaning in life. As much as I appreciate Florida’s previous work, I can’t get as exercised as he does about the New Urban Crisis.

Here’s an idea for election reform that everyone should be comfortable with: reducing the time voters spend in line at the polls.

Here’s an idea for election reform that everyone should be comfortable with: reducing the time voters spend in line at the polls. The consensus-building workgroup that fostered 2017 legislation to promote community solar energy in Virginia reconvened Monday to grapple with more intractable issues that stand in the way of widespread adoption of solar power.

The consensus-building workgroup that fostered 2017 legislation to promote community solar energy in Virginia reconvened Monday to grapple with more intractable issues that stand in the way of widespread adoption of solar power. Stephen Moret, CEO of the Virginia Economic Development Partnership (VEDP), brought a wealth of experience in corporate recruitment and workforce training when he moved to Virginia from Louisiana. But there’s another aspect of Virginia’s economic development chief that has gained little notice here in the Old Dominion. Last year he earned a doctorate in higher education management from the University of Pennsylvania.

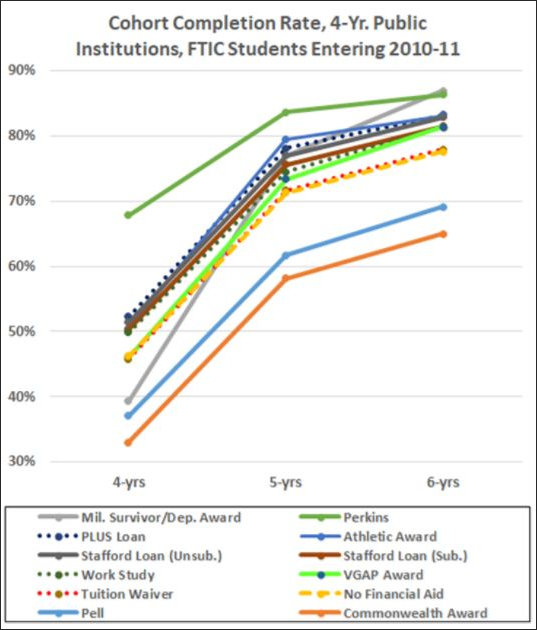

Stephen Moret, CEO of the Virginia Economic Development Partnership (VEDP), brought a wealth of experience in corporate recruitment and workforce training when he moved to Virginia from Louisiana. But there’s another aspect of Virginia’s economic development chief that has gained little notice here in the Old Dominion. Last year he earned a doctorate in higher education management from the University of Pennsylvania.

Yippee! I was struck from the Henrico County jury today, and I’m back to blogging. I was fully prepared to participate in the three-day jury trial of a man charged with heroin distribution, but someone — I’m betting it was the defense attorney — gave me the heave-ho.

Yippee! I was struck from the Henrico County jury today, and I’m back to blogging. I was fully prepared to participate in the three-day jury trial of a man charged with heroin distribution, but someone — I’m betting it was the defense attorney — gave me the heave-ho. I’m on jury duty today, so I won’t have time for blogging. But very quickly, a couple of articles worth noting….

I’m on jury duty today, so I won’t have time for blogging. But very quickly, a couple of articles worth noting…. by Donald J. Rippert

by Donald J. Rippert

Richard Florida, who gained renown 15 years ago with his book, “The Rise of the Creative Class,” is a progenitor of big ideas exploring the nexus of urbanism, innovation and prosperity, and he’s back with another book and another big idea. Having documented in previous works that a handful of “superstar cities” are sucking up the lion’s share of artistic, scientific, and entrepreneurial talent and creating a wildly disproportionate share of global wealth, he delves into the dark side of urban prosperity. The title of the new book lays out his thesis succinctly: “The New Urban Crisis: How Our Cities Are Increasing Inequality, Deepening Segregation, and Failing the Middle Class—and What We Can do About It.”

Richard Florida, who gained renown 15 years ago with his book, “The Rise of the Creative Class,” is a progenitor of big ideas exploring the nexus of urbanism, innovation and prosperity, and he’s back with another book and another big idea. Having documented in previous works that a handful of “superstar cities” are sucking up the lion’s share of artistic, scientific, and entrepreneurial talent and creating a wildly disproportionate share of global wealth, he delves into the dark side of urban prosperity. The title of the new book lays out his thesis succinctly: “The New Urban Crisis: How Our Cities Are Increasing Inequality, Deepening Segregation, and Failing the Middle Class—and What We Can do About It.”