by James A. Bacon

In 1968, nearly five decades ago, Edward C. Banfield wrote a brilliant analysis of urban problems in America: “The Unheavenly City.” Today, his contributions have been all but forgotten. But they are worth resurrecting because of their prescience. While optimists proclaimed that the expansive programs of the Great Society would conquer poverty, Banfield believed the opposite. “Unless lower-class persons display an unprecedented amount of upward mobility,” he predicted, “the lower-class population of the city may grow, perhaps rather rapidly.”

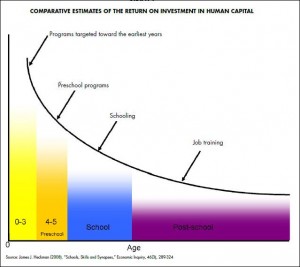

Despite the expenditure of trillions of dollars on the social safety net, urban renewal and anti-poverty programs, poverty is as deeply entrenched and endemic as it was when the Great Society was put into place. Liberals and progressives say the reason is that American society simply hasn’t spent enough money. Just fund pre-K, raise the minimum wage or address the food desert, and we’ll get there. But disciples of Banfield know otherwise, for those programs fundamentally misdiagnose the problem of poverty in America.

Banfield viewed the poverty through the prism of future orientation. He divided society into four classes — upper, middle, working and poor — based upon the ability of people to envision the future, defer present gratification for future reward, and control their impulses. Those who worked for the future would be upwardly mobile; those who lived present-oriented lives would be downwardly mobile. Present-oriented people would tend to collect in the lower economic classes, earning less money. More important than their material poverty, these peoples’ lives would be marked by violence, crime, alcohol and drug addiction, child abuse and all manner of other social pathologies.

The American welfare state has done a reasonable job at ameliorating material conditions of poverty. As Robert Rector and Rachel Sheffield, Heritage Foundation scholars drawing upon Census Bureau data, America’s poor have access to material possessions once considered luxuries: 80% have air conditioning, 92% own a microwave, nearly two-thirds have cable or satellite TV, and half have a personal computer; 82% of poor parents reported never being hungry due to a lack of money for food; the average poor American has more living space than the typical non-poor person in Sweden, France or the United Kingdom.

What makes the lives of American poor people miserable is not material deprivation but dysfunctional behavior. As Banfield wrote, “A slum is not simply a district of low-quality housing; rather it is one in which the style of life is squalid and vicious.”

The lower-class individual lives from moment to moment. If he has any awareness of a future, it is of something fixed, fated, beyond his control: things happen to him. He does not make them happen. Impulse governs his behavior, either because he cannot discipline himself to sacrifice a present for a future satisfaction or because he has no sense of the future. He is therefore radically improvident: whatever he cannot consume immediately he considers valueless. His bodily needs (especially for sex) and his taste for “action” take precedence over everything else — and certainly over any work routine. He works only as he must to stay alive, and drifts from one unskilled job to another, taking no interest in the work. …

In his relations with others, he is suspicious and hostile, aggressive yet dependent. He is unable to maintain a stable relationship with a mate; commonly he does not marry. He feels no attachment to community, neighbors, or friends (he has companions, not friends), resents all authority (for example, that of policemen, social workers, teachers, landlords, employers), and is apt to think that he has been “railroaded” and to want to “get even.” He is a nonparticipant: he belongs to no voluntary organizations, has no political interests, and does not vote unless paid to do so.

The lower-class household is usually female-based. The woman who heads it is likely to have a succession of mates who contribute intermittently to its support but take little or no part in rearing the children. … The stress on “action,” risk-taking, conquest, fighting and “smartness” makes lower-class life extraordinarily violent. … In its emphasis on “action” and its utter instability, lower-class culture seems to be more attractive to men than to women.

Banfield goes on to make various predictions that that idealists and social engineers plausibly could deny at the time but seem indubitably true after five decades of failed social policy: Continue reading