by James A. Bacon

The proposed route for the Atlantic Coast Pipeline runs through the mountain habitat of the Cow Knob salamander, creating a new rallying point for pipeline foes. National forest officials say the pipeline should be routed around salamander territory or even under it by drilling through Shenandoah Mountain, according to the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

“Even the most minor habitat alteration can cause detrimental effects to these salamanders,” says Jennifer Adams, special project coordinator for the George Washington and Jefferson National forests.

For its part, Dominion, managing partner of the pipeline, says it is working with federal officials to resolve the issue. “We are currently evaluating potential options and are planning to meet with the Forest Service to discuss these options that provide the avoidance it has requested,” said Dominion spokesman Jim Norvelle.

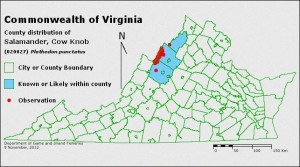

Virginia’s mountains are literally crawling with salamanders, many species of which are rare due to the fact that mountainous terrain creates isolated gene pools. Three species — the Shenandoah, the Peaks of Otter and the Big Levels — live only in Virginia. The Cow Knob salamander, whose range overlaps Virginia and West Virginia, is described by the Virginia and West Virginia Draft State Wildlife Action Plans as facing “an extremely high risk of extinction or extirpation.” The species enjoys a variety of conservation protections in the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests, Virginia’s largest wilderness area.

The proposed pipeline would “kill numerous Cow Knob salamanders” by destroying habit directly through forest clearing and indirectly by exposing the forest edge to sunlight, wind and edge predators, says H. Thomas Speaks Jr., Forest Service forest supervisor, in a letter to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Further, by dividing the salamander habitat into southern and northern portions, the pipeline will limit gene flow between the two populations, potentially threatening the viability of the southern population.

Bacon’s bottom line: On the face of it, this sounds like a win-lose proposition. Either the pipeline people win and the salamander loses, or the salamander wins and the pipeline project faces horrendous additional costs. But could there be a compromise?

Speaks’ letter emphasizes that the salamander is threatened by the loss and fragmentation of its habitat. Especially detrimental are utilities, roads and other types of development that penetrate the forest, creating a new “edge” ecosystem inhospitable to the Cow Knob salamander, especially to predators such as raccoons. Two questions: (1) Can Dominion mitigate the impact of its clear-cutting the forest to build the pipeline; and (2) can Dominion offset the impact by mitigating negative impact elsewhere, much as road builders might offset the loss of wetlands by creating wetlands elsewhere?

The Speaks letter mentions some possibilities:

- Restoration of currently disturbed habitats

- Acquisition of more habitat

- Permit vegetative cover of pipeline corridor suitable for Cow Knob salamanders

All of these measures will entail additional expense or inconvenience, which Dominion says will get passed on to pipeline customers. But that expense should be less than the cost of drilling 4,000 feet through Shenandoah Mountain or selecting a different, longer pipeline route.