by James A. Bacon

In 1968, nearly five decades ago, Edward C. Banfield wrote a brilliant analysis of urban problems in America: “The Unheavenly City.” Today, his contributions have been all but forgotten. But they are worth resurrecting because of their prescience. While optimists proclaimed that the expansive programs of the Great Society would conquer poverty, Banfield believed the opposite. “Unless lower-class persons display an unprecedented amount of upward mobility,” he predicted, “the lower-class population of the city may grow, perhaps rather rapidly.”

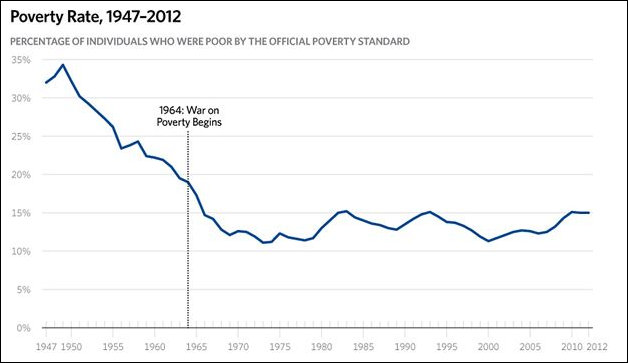

Despite the expenditure of trillions of dollars on the social safety net, urban renewal and anti-poverty programs, poverty is as deeply entrenched and endemic as it was when the Great Society was put into place. Liberals and progressives say the reason is that American society simply hasn’t spent enough money. Just fund pre-K, raise the minimum wage or address the food desert, and we’ll get there. But disciples of Banfield know otherwise, for those programs fundamentally misdiagnose the problem of poverty in America.

Banfield viewed the poverty through the prism of future orientation. He divided society into four classes — upper, middle, working and poor — based upon the ability of people to envision the future, defer present gratification for future reward, and control their impulses. Those who worked for the future would be upwardly mobile; those who lived present-oriented lives would be downwardly mobile. Present-oriented people would tend to collect in the lower economic classes, earning less money. More important than their material poverty, these peoples’ lives would be marked by violence, crime, alcohol and drug addiction, child abuse and all manner of other social pathologies.

The American welfare state has done a reasonable job at ameliorating material conditions of poverty. As Robert Rector and Rachel Sheffield, Heritage Foundation scholars drawing upon Census Bureau data, America’s poor have access to material possessions once considered luxuries: 80% have air conditioning, 92% own a microwave, nearly two-thirds have cable or satellite TV, and half have a personal computer; 82% of poor parents reported never being hungry due to a lack of money for food; the average poor American has more living space than the typical non-poor person in Sweden, France or the United Kingdom.

What makes the lives of American poor people miserable is not material deprivation but dysfunctional behavior. As Banfield wrote, “A slum is not simply a district of low-quality housing; rather it is one in which the style of life is squalid and vicious.”

The lower-class individual lives from moment to moment. If he has any awareness of a future, it is of something fixed, fated, beyond his control: things happen to him. He does not make them happen. Impulse governs his behavior, either because he cannot discipline himself to sacrifice a present for a future satisfaction or because he has no sense of the future. He is therefore radically improvident: whatever he cannot consume immediately he considers valueless. His bodily needs (especially for sex) and his taste for “action” take precedence over everything else — and certainly over any work routine. He works only as he must to stay alive, and drifts from one unskilled job to another, taking no interest in the work. …

In his relations with others, he is suspicious and hostile, aggressive yet dependent. He is unable to maintain a stable relationship with a mate; commonly he does not marry. He feels no attachment to community, neighbors, or friends (he has companions, not friends), resents all authority (for example, that of policemen, social workers, teachers, landlords, employers), and is apt to think that he has been “railroaded” and to want to “get even.” He is a nonparticipant: he belongs to no voluntary organizations, has no political interests, and does not vote unless paid to do so.

The lower-class household is usually female-based. The woman who heads it is likely to have a succession of mates who contribute intermittently to its support but take little or no part in rearing the children. … The stress on “action,” risk-taking, conquest, fighting and “smartness” makes lower-class life extraordinarily violent. … In its emphasis on “action” and its utter instability, lower-class culture seems to be more attractive to men than to women.

Banfield goes on to make various predictions that that idealists and social engineers plausibly could deny at the time but seem indubitably true after five decades of failed social policy:

So long as the city contains a lower class, nothing basic can be done about its most serious problems. … Slums may be demolished, but if the housing that replaces them is occupied by the lower class it will shortly be turned into new slums. Welfare payments may be doubled or tripled and a negative income tax instituted, but some persons will continue to live in squalor and misery. New schools may be built, new curricula devised, and the teacher-pupil ratio cut in half, but if the children who attend these schools come from lower-class homes, they will be turned into blackboard jungles, and those who graduate or drop out from them will, in most cases, be functionally illiterate.

Banfield was right. Anti-poverty programs did not end poverty; they entrenched poverty. Source: Heritage Foundation.

How about universal pre-K? Banfield would agree with the premise of universal pre-K that changing the culture of the lower-class child involves intervening in its early years. Lower-class children would benefit from day nurseries, he wrote, but for the fact “that they are at once confused and stultified by what they are (and are not) exposed to at home.” The only way to accomplish the goals that pre-K advocates wish to achieve– to put children on a level educational playing field — is to remove the children entirely from lower-class culture. The implication, he wrote, is that “the child should be taken from its lower-class parents at a very early age” and brought up by people not steeped in lower-class culture. But that idea is a non-starter because the state has no right to take children from their parents to prevent an injury as “impalpable” as its socialization into lower-class culture.

How about job training? “Training programs do not as a rule offer any solutions to the problem of hard-core unemployment,” Banfield wrote, because the same qualities that make a worker hard-core also make him unable or unwilling to accept training.”

Was Banfield a fatalist? Did he believe that nothing can be done to help the poor? Not at all. But he was a realist who recognized that many anti-poverty programs are either useless or counterproductive. Among his observations:

- Distinguish between different types of poverty. Some people are poor because of adverse situations, such as the loss of a job. With help, they can get back on their feet. Others are poor because they are radically present-oriented and reject boring, bourgeois lifestyles. Programs that help the former will do nothing for the latter.

- Anti-poverty programs produce perverse incentives. Programs designed to ameliorate the material conditions of the poor encourage behavior that perpetuates poverty. Why trade immediate gratification in order to complete schooling and acquire skills that might lift one into a marginally preferable working-class lifestyle years from now?

- Don’t destroy jobs for the poor. Remove impediments to the employment of the “unskilled, the unschooled, the young” by repealing minimum wage, occupational licensure laws and laws that give labor unions monopolistic powers.

- Stop obsessing about high school graduation rates. “Our cultural ideal requires that we give every child a good education whether he wants it or not and whether he is capable of receiving it or not.” Letting students drop out after ninth grade would free resources and reduce disruption for those students are are inclined to learn.

- Stop concentrating poor people geographically in inner cities. Don’t let them create a “critical mass” in which the lower-class culture becomes the predominant culture.

Banfield propounded other controversial ideas. Give intensive birth-control guidance to the poor, especially young women, who are less hard-wired toward a present-orientation than young men. Permit the police to “stop and frisk” in high-crime areas, make misdemeanor arrests on probable cause and — the missing element in today’s practice — pay compensation to suspects who are held in jail and later found to be innocent. He also argued idealistically for “guaranteed loans for higher education to all who require them.” He did not foresee the resulting student loan crisis as millions took on student debt to enroll in programs they never completed, leaving them burdened with loans they cannot repay.

Banfield’s skepticism runs counter to the widespread conviction that American society must DO SOMETHING, and that the doing is more important than the results. “The doing of good is not so much for the benefit of those to whom the good is done as it is for that of the doers, whose moral faculties are activated and invigorated by the doing of it. … By far the most effective way of helping the poor is to keep profit-seekers competing vigorously for their trade as consumers and for their services as workers; this, however, is not a way of helping that affords members of the upper classes a chance to flex their moral muscles or the community the chance to dramatize its commitment to the values that hold it together.”

In the final analysis, Banfield focuses on results, not good intentions. Nearly 50 years later, anti-poverty programs have had abundant opportunity to evolve and mature. It is more than time now to measure the results, to see what works, and to dispense with what does not.