There is a sterile quality to the debate over universal childhood education. Liberals cite studies that say that it makes sense to invest in pre-school for poor children on the grounds that it increases the odds that kids will perform better academically, thus less likely to drop out of school, more likely to get a job, and less likely to get incarcerated, saving society billions of dollars in the long run. Noting that pre-school can’t overcome the affects of dysfunctional families and lousy schools, skeptics (usually conservatives) say the positive effects fade within a few years and question whether creating another massive entitlement program will do any good.

As a society, we’re desperate to find something that helps poor children overcome the debilitating consequences not only of material poverty but an upbringing so impoverished that many don’t know their colors, numbers or ABCs by the time they enter kindergarten.

James V. Koch, professor emeritus of Old Dominion University, puts a different spin on the pre-K issue in the “State of the Region: Hampton Roads 2015.” He sides with those who believe that high-quality early childhood education has a large positive benefit but proposes a funding source for pre-K that makes the idea more palatable to conservatives.

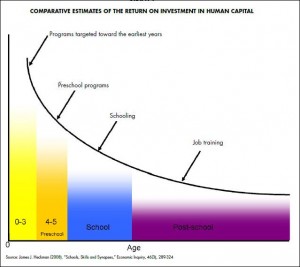

Drawing upon the work of Nobel Laureate James Heckman, Koch argues that social investment in human capital accomplishes more in a child’s early, formative development than later in life when his or her cognitive abilities have been largely set. As seen in the conceptual graph above, investing in enriching a child’s development at ages 0-3 yields a higher return than in preschool, which in turn provides a higher return than school, which in turns pays back more than job training.

Koch cites the famous Perry Preschool Project which began in Ypsilanti, Mich., in the 1960s. A $21,000 per pupil investment (in today’s dollars) yielded cumulative savings of $240,000 by age 40. Whether those results could be replicated is the subject of debate. But an even bigger problem is political. Someone is going to have to pay for universal pre-K. Middle-class parents are not likely to be thrilled about paying more in taxes so poor children can attend programs that cost two to three times what they can afford for their own children.

That political calculus could change if the funding comes from elsewhere. Writes Koch: “There is now a strong argument for shifting resources away from later-in-life job training programs and re-directing them to early childhood programs.” But that creates a political problem of its own, he concedes: Benefits from early-childhood programs take years to become manifest; the pain of training cutbacks is immediate.

Koch advances another novel argument: Early childhood education is good economic development.

One must compare these salutary results with the much less impressive outcomes that are generated by conventional businesses subsidies (usually tax incentives) that government units at all levels habitually utilize in hopes of improving their economic situations. … In general, tax incentives yield low returns for cities and counties that rely upon them, and typically yield negative returns for regions and states.

Bacon’s bottom line: I’m skeptical of the whole ball of wax — early childhood intervention, government-administered job training programs, business subsidies, tax incentives, you name it. But if government has got to “do something” to reverse the pathologies and dysfunctions created by previous efforts to “do something,” then voluntary universal pre-K arguably would make a better long-run investment than jinky tax breaks and duplicative and ineffectual job training programs. Make universal pre-K spending neutral by cutting less effective programs, and I just might buy into it.