Casp Alimentacion -- no Slurpees here. But you can find Fanta and Red Bull.

by James A. Bacon

If you live on Carrer de Girona in Barcelona, as my family and I have for the past few days, and you have a sudden craving for a green pepper, a bottled water, a Filipinos chocolate treat or a Red Bull at 11:00 at night, you just roll out of the front door of your apartment building, stroll around the corner and walk into the Casp Alimentacio, which is “sempre obert,” always open. The hole-in-the-wall shop, which is a bit like a 7 Eleven without the Slurpee machines, stocks essential staples demanded by its clientele, the vast majority of whom live within a few minutes’ walk.

Casp Alimentacio would never survive in an American suburb, in which the number of households living within a short stroll could be counted on two hands. But the economics are very different in Barcelona, where buildings are packed wall to wall along every street, reach five stories high and jam dozen households in less space than it would take to hold a single American dwelling.

Sidewalk scene in front of 27 Girano. Note the two-lane bicycle lane and the restaurant tables on the sidewalk.

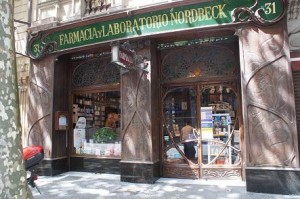

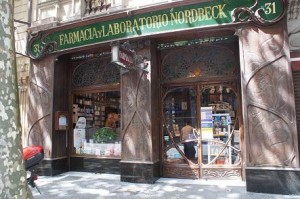

There are inconveniences associated with a dense urban setting, such as living in tight living quarters and the difficulty of finding parking spaces for your car. But there are compensating advantages, such as the proximity of groceries, restaurants and pharmacies within easy walking distance, as well as the existence of so many transportation alternatives that you can get along quite comfortably without an automobile.

One of two pharmacies on the block.

Rather than discuss the wonders of Barcelona’s mid-rise density and mixed-use development in the abstract, I thought it would be useful to show those land use features in a real-life microcosm, here at the Carrer de Girona apartment where we are staying. I have navigated the block, taking photos of shops like Casp Alimentacio, neighborhood restaurants and other business establishments, as well as the streets themselves, to show the vibrancy of the Barcelona way of life.

The neighborhood hardware store.

As luck would have it, my first outing occurred Tuesday, which, unknown to me, was a public holiday, the Assumption of Mary. Almost everything was shut down. Wow, this place is dead, I thought. And given the proclivity of vandals for spray painting graffiti on virtually every pull-down, corrugated metal door on every store in the city, the neighborhood looked like it was falling part. After learning of the holiday, however, I took another spin around the block. The place was much busier this morning, although there still were many empty storefronts. After all, it’s August, which means half the country is on vacation, many shopkeepers have closed their stores and many patrons have departed. Too, Barcelona’s economy, hobbled by Spain’s euro-crisis, is in unhappy condition and many businesses have closed in recent years. Moreover, the neighborhood is, shall we say, “in transition.” Long-term economic trends have pushed out many of the old commercial tenants, and Barcelona’s economy has not yet reinvented itself sufficiently to replace them all.

Still, all things considered, the commercial life of the block of 27 Girona is remarkably vibrant. An amazing number of people ply their trade and carry out routine daily activities in the very same part of town where they live.

The absolute essentials: cigs and lottery tickets.

The contrast with Virginia, where people must hop in their cars and drive from cul de sac neighborhoods to “shopping centers” or “office parks” could not be more marked. I’m not saying that Barcelona is better, but I am saying that it is very different — and that it seems to work. And because it works, it challenges many notions about transportation and land use that Virginians take for granted.

By way of background, Girona is situated in a district of Barcelona, the Eixample, that was laid out in the mid-1800s by sublimely rational urban planners. The street system was a rigid grid, with each block 100 meters in length. The corners were cut off, creating sort of an octagonal shape, to allow horse-drawn carriages to turn corners more easily. The configuration adapted nicely to the mechanized age by creating places to park cars, motorbikes — and big, squat garbage/recycling bins. The streets are 10 meters wide, which allows room for two car lanes and a bicycle lane, while the sidewalks are 5 meters wide, allowing plenty of space for motor scooters, restaurant tables and other street life.

The streets of Barcelona's Eixample district have a good number of empty storefronts -- all of them marked by graffiti.

The streets are lined with tall trees, which create plenty of shade. In this part of town, the buildings on the back streets are uniformly five floors high, with the ground-level reserved for small shops and businesses, and the upper floors usually set aside for apartments and condominiums. Each apartment building is the same height and width, the windows reach from floor to ceiling and balconies are placed under every window, seemingly a formula for monotonous conformity. But builders and architects have created delightful variety in the stonework of the building facades and ornamentation, the shape and color of the windows, the use of cupolas and the jutting of windows over the sidewalk. The architecture is a pleasure to the eye. Isabel and Mike, the owners of our apartment who lived next door to our apartment until about two weeks ago, describe the neighborhood this way:

Most people in the immediate area are wealthy and well-educated by Catalan standards and you would describe them as middle-class. Many of our neighbours have inherited their apartments and typically they have second homes in the countryside or in the coastal villages where they tend to head for weekends and holidays. Children tend to go to private schools. There has also been an influx of wealthy European residents in the last 10 years which has helped to support the local economy. It’s a particularly safe area to live in. The crime rate (if you discount tourists being pickpocketed!) is low and violent crime is very rare. You also won’t see public alcohol-related problems.

(Let me take this opportunity to put in a plug for our apartment. Check out Isabel and Mike’s home page at Sweet Home Barcelona.)

A "Bicing" station on the block provides a useful transportation option for a city with a Mediterranean climate.

There are, in our block alone, two active corner restaurants and two grocery establishments, two pharmacies, several clothing stores, a pilates center, a hardware store, a travel agency, a parking garage and a couple of businesses of indeterminate nature. There is a bank across the street as well as some kind of professional school (I can’t tell you what kind because I can’t read Catalan). In sum, there is a lot going on. If you were a free-lance IT consultant like Isabel and Mike are, you could have met your routine needs for days at a time without ever needing to walk more than a block or two. Should you need to go travel a greater distance, the city maintains a “Bicing” shared bicycle service on the far side of the block, and there are three METRO stations within a couple of blocks.

How does one explain all the empty commercial spaces? To anticipate the in-your-face reaction of Bacon’s Rebellion readers, if mid-rise, mixed use development is such a super-duper idea, why can’t it support more local business? I posed that question to Isabel and Mike. They responded:

Some store fronts in the area are vacant, but this has been the situation for a long time – not just in recent years – part of the reason is because many of the premises are very large because they housed large textile suppliers (the wealth of Barcelona was built on textiles in the 19th and early 20th centuries). Many of the textile factory owners lived in the area known as the Quadrat d’Or which includes the apartment that you are renting. The store owners try to rent out the whole premises (frequently there are conditions on the deeds of the buildings that prevent shops from being sub-divided) but obviously this somewhat limits their market. One recent change to this was the set-up of a car park last year in Carrer de Casp opposite the pizza restaurant. This was previously a textiles warehouse – the textile company had moved to a location out of town and the warehouse had been empty for several years until the owners decided to convert it because they couldn’t find anyone to let it.

Spaniards are very fashion conscious.... but six clothing stores... all for women... in a single block? Really?

Clearly, Carrer de Girona’s land use does not insulate the neighborhood from short-term economic fluctuations such as the current euro crisis nor from long-term secular changes such as the restructuring of the textile industry. The real question is this: How adaptable is the system? I would submit that, once you separate out the difficulties tied to the euro zone crisis and the transfer of wealth from affluent Barcelona to poorer parts of Spain, Barcelona’s system of medium-density land use is very adaptable. Developers are gutting several older buildings, taking care to preserve the magnificent historical facades, and are rebuilding them to meet current market demands. Also, as Barcelona shifts to an increasingly knowledge-driven economy populated with small business start-ups, the ubiquity of abundant, inexpensive office space should prove to be a tremendous asset to entrepreneurialism.

Sign of hard times: homeless man around the corner from our apartment.

What lessons does Barcelona hold for Virginia? Barcelona’s land use patterns would be impossible to replicate wholesale in the Old Dominion, even if people deemed them desirable. But there may be occasions to phase in compact, medium-density development at suitable locations. For instance, the Manchester district across the James River from downtown Richmond, where many of the old buildings have been leveled, could be organized around grid streets, mixed uses and multi-story buildings. Likewise, it might be possible to recycle old malls, with their giant parking lots, into mini-Eixamples.

But building three or four blocks would not generate all the benefits of comparable development in Barcelona. What makes the transportation system work in the Catalonian capital is the existence of hundreds of blocks like 27 Girona with sufficient population to sustain bus lines, the bicycle-sharing program and a Metro system. Still, the development pattern is worth experimenting with. Anything that economizes on the cost of maintaining infrastructure and that reduces the length and number of automobile trips has important advantages over scattered, low-density sprawl.

As seen in the photo above, someone applied a rough-textured material to the glass windows of an adjacent building to create an arresting visual effect. I suppose you might call it art. Whatever term you use, the material injects an element of the unpredictable. So did the odd piece of metal-and-wool craftsmanship to the right. The object (I don’t know what else to call it) is not exactly art for the ages, but it is whimsical and fun. I expect that we’ll see a lot more creations like these, as artists and philanthropists donate more pieces.

As seen in the photo above, someone applied a rough-textured material to the glass windows of an adjacent building to create an arresting visual effect. I suppose you might call it art. Whatever term you use, the material injects an element of the unpredictable. So did the odd piece of metal-and-wool craftsmanship to the right. The object (I don’t know what else to call it) is not exactly art for the ages, but it is whimsical and fun. I expect that we’ll see a lot more creations like these, as artists and philanthropists donate more pieces. In a sure sign that the High Line is creating economic value, property owners have begun touting proximity to the park as a selling point for renters. “Home on the High Line!” proclaims the banner to the right, displayed to joggers and pedestrians on the elevated path. Property owners also are promoting a High Line location for business offices. “High Line Your Business,” exhorts signage overlooking the urban trail, morphing the name of the park into a verb.

In a sure sign that the High Line is creating economic value, property owners have begun touting proximity to the park as a selling point for renters. “Home on the High Line!” proclaims the banner to the right, displayed to joggers and pedestrians on the elevated path. Property owners also are promoting a High Line location for business offices. “High Line Your Business,” exhorts signage overlooking the urban trail, morphing the name of the park into a verb.