Andres Duany. Photo credit: Miami Herald

by James A. Bacon

Never in all the times over the years that I have heard Andres Duany speak, nor in those occasions in which I interviewed him, have I heard him utter a scintilla of partisan political sentiment. If I had to guess, I would say that he disdains both political parties. As he said yesterday of the New Urbanism movement, “We’re non-ideological. I can’t emphasize that enough.” New Urbanists are interested, he said, in “what works over the long run.”

But to say that Duany, the godfather of the New Urbanism movement, is non-partisan and non-ideological is not to say that there is no ethical basis for his thinking. Indeed, when he was providing an overview of New Urbanism basics to newby attendees of the 2014 Congress for the New Urbanism conference, he commenced with a discourse on the movement’s ethics.

Environmentalism is an ethical imperative that gives primacy to nature, nature’s creatures and the natural habitat. By contrast, New Urbanism puts people at the center. “The New Urbanism cares about the human habitat — not about the polar bears. How’s our species doing?”

Duany describes his way of thinking as old-fashioned “American pragmatism.” He asks how the built environment affects people. He wants to know what works. To use philosophical jargon, he is an empiricist. While he offers detailed prescriptions about the best way to build communities, he is ever-ready to revisit old assumptions on the basis of new evidence. One of the most fascinating things about listening to him year after year is to hear how his thinking changes based upon the experience of New Urbanism projects in the real world.

Duany is best known for his critique of suburban sprawl, the low-density auto-centric pattern of development that has prevailed in North America since World War II. Sprawl communities were built for the care and feeding of automobiles, not people. He is no fan either of spectacular “starchitect”-designed buildings that lavish attention on the buildings while sacrificing the public realm where people actually interact. Likewise, while he is ever receptive to new techniques, he is skeptical of those who tout technology or other silver bullets as magical solutions to incredibly complex problems.

There is a strong libertarian streak in Duany’s thinking. Perverse government regulations — zoning codes that segregate land uses, Department of Transportation specifications that mandate crazy-wide streets, fire marshal regulations that make it impractical to build alleyways through city blocks — are the frequent target of his ire. Government rules are full of unintended consequences. (He has deepened his critique of over-regulation in his recent emphasis on Lean Urbanism.) How is it possible, he asked yesterday, that in the 19th century the United States managed to house 30 million penniless immigrants with no government assistance while today, with massive government involvement, the country is completely incapable of housing poor people properly?

Duany respects market forces. He is acutely aware that development projects must make money for developers (his clients) and be affordable to buyers. Accordingly, he is always alert to materials, building techniques, regulatory work-arounds and other strategies to drive costs out of building New Urbanist communities without compromising core principles.

That libertarianism is leavened, however, by a Burkean conservatism that respects the classical patterns that evolved over millennia of trial and error. The English thinker Edmund Burke found value in the wisdom accumulated over generations and argued that old habits and practices should not be lightly discarded. Likewise, Duany finds value in the old, human-scale patterns of architecture and city design handed down over the ages until tossed aside by the radical disruption of the automobile culture.

Finally, Duany maintains a healthy skepticism toward the social engineers and visionaries who put ideology first. “We don’t experiment on people,” he said. Too many experiments in urban development — Pruitt Igoe-style public housing, anyone? — have proven disastrous. Given the slow turnover in the built environment, the effect of bad ideas lasts for decades.

Currently, that skepticism manifests itself in his awkward relationship with environmentalists. One of the best things that happened to the New Urbanism movement is when the environmentalists discovered that it offered a fully blown critique and alternative to auto-centric sprawl. “We’re now riding the ecological movement,” he said: “Fewer cars, less pavement.” But environmentalists can get carried away, whether they’re protecting snail darters or polar bears or they’re advocating expensive LEED certification that drives up the cost of new buildings. He decried the consultants — “a whole profession of sucker fish” — who have arisen around implementing the standards. Too many experts insist upon expensive, high-tech solutions while low-tech solutions, many of them found in vernacular architecture that uses passive techniques to heat and cool, will conserve energy far more cost effectively.

With a curious, wide-ranging mind, Duany is prone to digressions. At the moment, he is fascinated by the city plans adopted by 19th-century Mormons, and he’s updating the ideas of Ebenezer Howard, the 19th-century English author of “Garden Cities of Tomorrow,” the forerunner of modern suburbia, to create a yardstick for measuring modern garden-city revival projects. Pretty esoteric stuff. But in the end, he always comes back to what works, what kinds of communities best meet human needs.

Duany’s refusal to be pigeon-holed ideologically is one of the reasons for New Urbanism’s success. An appreciation of walkable, human-scale communities is penetrating all levels of government and society. That’s happening because, as a non-partisan movement, New Urbanism does not alienate partisan elected officials. It probably doesn’t hurt that Duany’s approach also appeals to a populace that is increasingly disenchanted with technocrats and ideologues.

He does not cast New Urbanists as heroes who swoop in and save the world. Rather, New Urbanists help define the rules that enable ordinary people to improve their lives and communities. “Patient, long-term investment is what works,” he said. “We set things up so communities can heal themselves.”

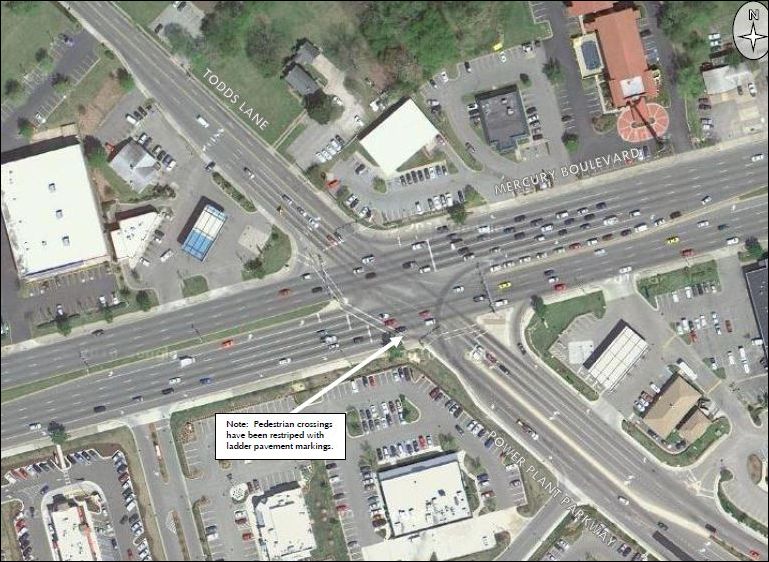

And here is a 10-minute drive in Chesterfield:

(Admittedly, parking is a nightmare in New York compared to Chesterfield. On the other hand, Manhattan provides transportation options — walking, biking, buses and the subway — that are either impractical or do not exist in Chesterfield.)

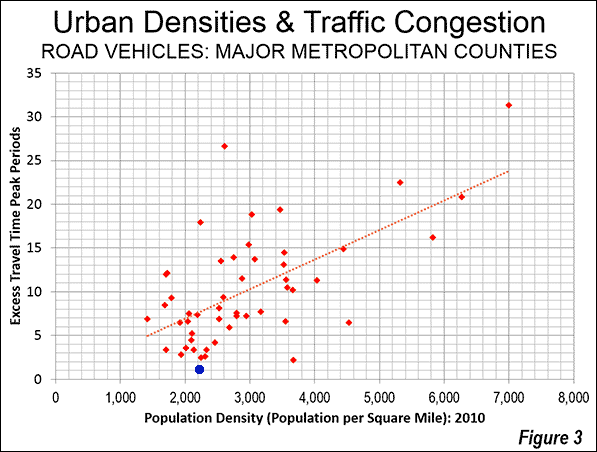

Cox dwells on the fact that density creates congestion. He is quite correct about that. But he ignores the fact that density also creates access. It’s access, not mobility, that is critical to economic growth and quality of life.