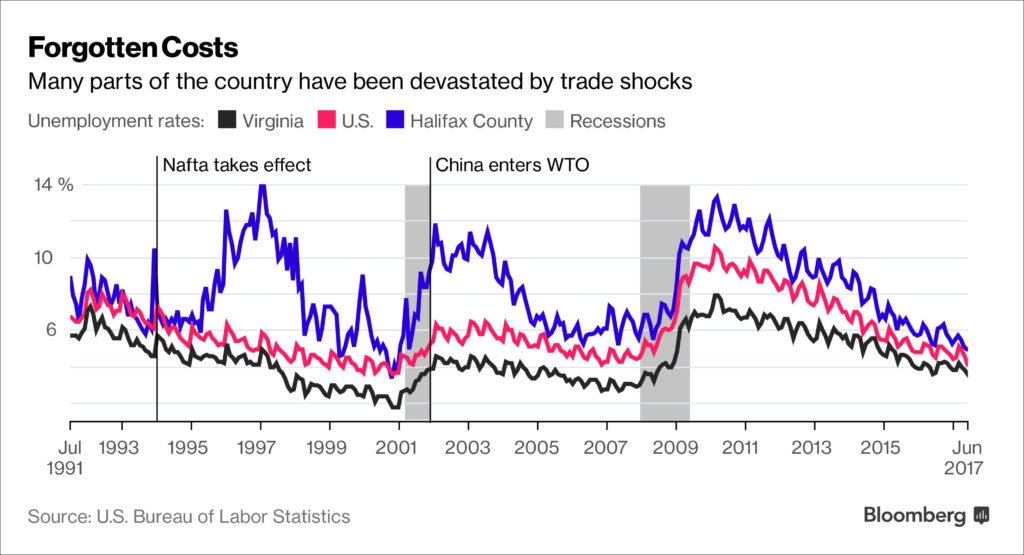

Ralph Northam, Democratic Party candidate for governor, grew up on the Eastern Shore, so it’s not surprising that he has given considerable thought to the challenges of economic development in Virginia’s small towns and rural communities. Earlier this week, he unveiled his plan for economic growth in rural Virginia.

If you’re looking for a “Marshall Plan” to reinvigorate rural Virginia, this is not it. The plan is not ambitious, and there may not be enough in it to get rural Virginians especially excited about Northam’s candidacy. But it has this virtue: Proposals don’t require spending vast sums of money, so they are at least feasible from a budgetary perspective. This is a plan that Northam, if elected, has a realistic chance of implementing.

Personally, I distrust “Marshall Plan” approaches to chronic social and economic challenges. Instead, in our fiscally constrained era, I’m a fan of low-cost, low-risk initiatives that will likely yield a positive return on investment. In that spirit, I’ll start by illuminated the most promising ideas in the Northam plan and work my way down the list.

Virginia’s Rapid Readiness Program. Northam proposes a “rapid readiness program” similar to successful workforce training programs in Georgia and Louisiana. “We could get this program started here in Virginia with a ten million dollar investment, with funding tied to business participants, number of projects delivered, and individuals successful trained,” states his plan.

Assuming that Northam is drawing upon the thinking of Virginia Economic Development Partnership CEO Stephen Moret, who set up the Louisiana program, the program would function as a extension of Virginia’s economic development effort by offering a workforce-training solution as an incentive for corporations to invest in Virginia. The program would differ from existing educational/training offerings by creating a team capable of providing customized training within a time frame required by corporations to get their operations up and running.

While the rapid readiness program would be applied across the state, rural areas arguably would benefit the most because such training applies most frequently to light manufacturing projects that typically locate in smaller communities.

I’m not sure $10 million is sufficient to fund this program properly. Regardless, there is a readily available pot of money — Northam and Moret no doubt would disagree with me about this — and that is the Commonwealth Opportunity Fund, which the state dips into to provide “incentives” for economic development projects. But as Moret himself said in a presentation to the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia two days ago, workforce is one of the top three factors (and often the No. 1 factor) that corporations consider when deciding where to locate. Incentives are a secondary factor. Shifting money from incentives to workforce training looks like a no-brainer to me.

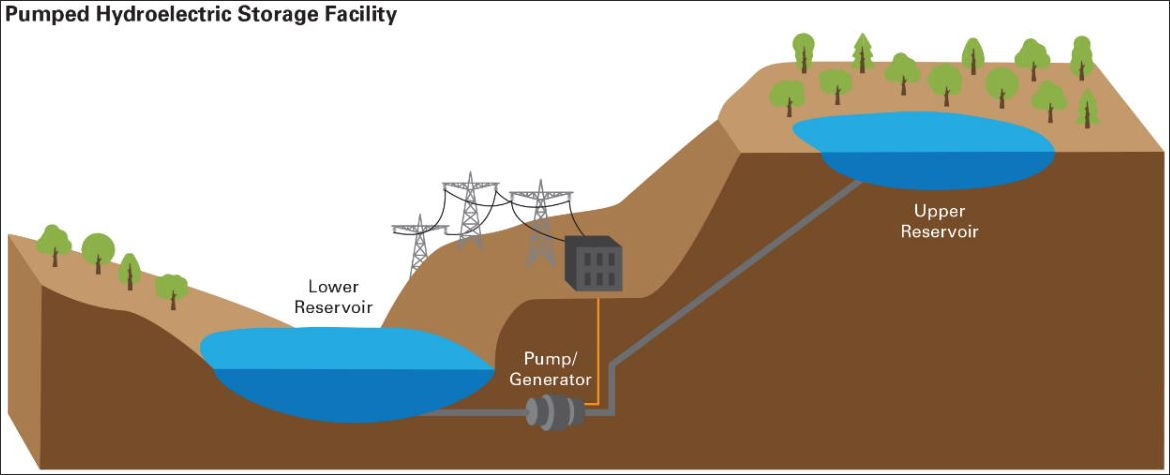

Expanding renewable energy. Expanding solar generation is viable rural economic development strategy. Solar farms may create few permanent jobs, but they do increase the tax base, and they often pay streams of royalties to landowners (depending on how particular deals are structured).

“In my home county of Accomack on the Eastern Shore,” says Northam, “the commonwealth’s largest solar farm is in the process of being built, which will ultimately power several data centers owned by Amazon.”

Northam says he is committed to working with Virginia’s electric utilities and the General Assembly to “remove barriers that stand in the way of developing and expanding clean energy efforts.” Note the phrase “remove barriers.” Northam is not asking for new subsidies or tax breaks. Solar doesn’t need subsidies; market forces increasingly favor solar. Rather, Northam wants to remove obstacles that inhibit businesses, entrepreneurs and homeowners from building rooftop solar and solar farms.

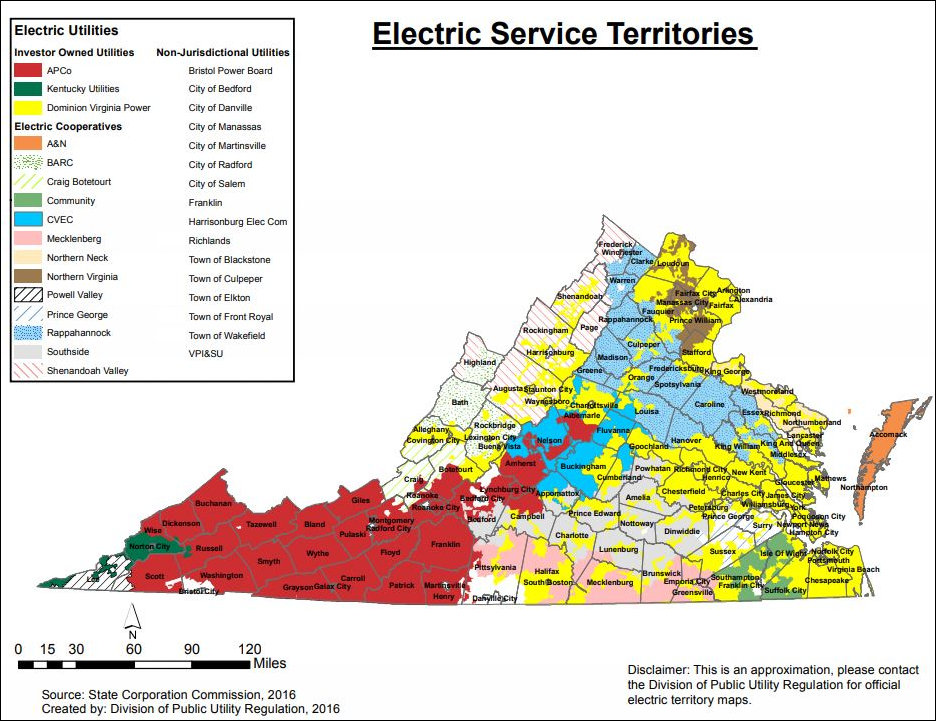

Utility-scale solar like the Amazon Web Services farms in Accomack need little help — Dominion Energy and Appalachian Power have ample incentive to deploy solar on a large scale. The barriers exist at two levels: local zoning codes and state regulatory policy. Local governments need to make their zoning codes more solar friendly. Meanwhile, state lawmakers need to craft “net metering” legislation that balances the interests of independent solar producers with those of electric utilities who maintain the electric power grid that everyone depends upon.

Broadband for all. Most people would accept the proposition that broadband Internet service is critical infrastructure for economic development today. The problem is that sparsely populated rural areas are not attractive markets to Virginia’s big broadband providers.

Northam points to a pilot project in Southside Virginia in which Virginia’s Tobacco Commission, Microsoft, and the Mid-Atlantic Broadband Company utilize unused portions of the television broadcast spectrum to push out high-quality wireless broadband. So far, more than 100 households have been connected, and the number could reach 1,000 by year’s end.

“Under this innovative public-private program, Virginia’s share of the cost is $500,000, leverage private investment for a total investment of $1 million,” states the Northam plan. “This commonwealth should look to replicate this successful program across rural Virginia.”

How so? He would pull together disparate broadband initiatives across the commonwealth under the direction of a cabinet official “who will be responsible for getting more people connected.” Northam also advocates legislation similar to that adopted in Minnesota that creates a clear set of metrics, including upload and download speeds, to evaluate broadband access. Whatever else you say about these proposals, it doesn’t sound like they will break the bank.

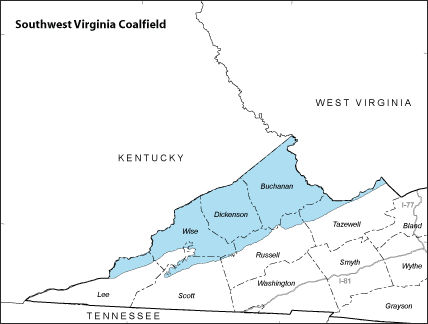

Expanding the University of Virginia-Wise. Northam proposes increasing the educational offerings of the University of Virginia-Wise to encompass high-need, high-growth disciplines such as cybersecurity, unmanned aerial systems, energy, and computer engineering and programs. Expanding UVa-Wise would cost about $15 million initially, Northam says, with a possibility of scaling up funding over time.

We have a unique opportunity … to transform UVA-Wise into an international destination for students and researchers. This will have a tremendous effect on the regional economy because when you can attract students and top talent from around the world for research and development, grants will follow. And with grants and applied research, business opportunities will soon follow. And structured correctly, these businesses will not only start up in Southwest Virginia, but they will remain and grow.

The idea of creating “innovation districts” around college campuses is a hot one right now, and anyone who has seen the Virginia Tech Corporate Research Center can readily understand the potential for economic development near college campuses. But Tech is the top research university in the state. Whether its success can be replicated on even a modest scale by a tiny, largely unknown newcomer is questionable. Tech has invested hundreds of millions, maybe billions, of dollars, over decades building academic programs, hiring star faculty, recruiting graduate students, and assembling the administrative infrastructure it takes to win research contracts.

Competing for research dollars is tough. Well established institutions such as Old Dominion University and the College of William & Mary have seen their research programs falter in recent years. It is a stretch to suggest that a $15 million investment in Wise would spark the miraculous transformation that Northam describes.

Startup tax plan. To help attract and retain new business in rural and economically depressed regions of Virginia, Northam proposes a “zero BPOL and merchant’s capital tax for new startup and small businesses .. for the first two years. This will drive economic activity and startups to rural areas, and result in no loss in existing revenue to local governments.” Once local businesses take root, they will start paying taxes — a win-win.

It’s good to see a Democratic Party candidate advocating tax cuts! But the proposal lacks crucial detail. BPOL and merchant’s capital taxes are local taxes. How does Northam propose eliminating those taxes for two years? Will the state just command localities to change their ordinances? Will the state reimburse them for lost revenue? Does he have the remotest idea of what the initiative would cost? Finally, while the BPOL and merchant’s capital taxes are near the top of the list of things that small businesses in Virginia hate, is there any body of evidence suggesting that a mere two-year reprieve will stimulate more startups?

There’s more to Northam’s plan, but the other proposals, which address workforce development, are statewide in nature and don’t address peculiarly rural issues. So, I won’t dwell on them here.

Perhaps the best thing that can be said about this plan is that Northam isn’t making extravagant promises that he can’t keep. These narrow-bore proposals won’t exactly spark a rural Renaissance, but for the most part, they seem politically and fiscally feasible.

I would like to expand upon the idea. By my count there are four cities — Bristol, Radford, Galax and Norton — in Southwest Virginia and more than 40 incorporated towns. The towns range in size from Blacksburg (population 44,200) to Clinchport (population 67) in Scott County — both the largest and the smallest in the Commonwealth. Many of these cities and towns have walkable Main Streets or downtown districts capable of supporting mixed use development.

I would like to expand upon the idea. By my count there are four cities — Bristol, Radford, Galax and Norton — in Southwest Virginia and more than 40 incorporated towns. The towns range in size from Blacksburg (population 44,200) to Clinchport (population 67) in Scott County — both the largest and the smallest in the Commonwealth. Many of these cities and towns have walkable Main Streets or downtown districts capable of supporting mixed use development.