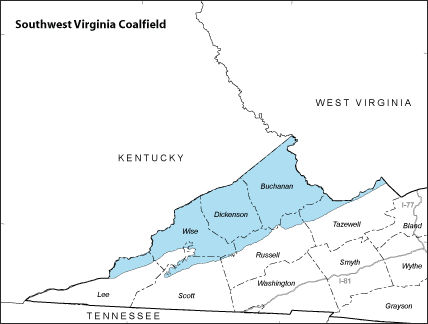

Map credit: Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy

A Roanoke Times editorial asks a provocative question: “Should we just let Appalachia go?” Instead of trying to rebuild a new economy in far Southwest Virginia, should the commonwealth just allow the region to depopulate?

As the editorial points out, the Appalachian mountains and hollers were sparsely populated through the 18th and 19th centuries. Then, in the late 1800s there arose an industrial economy that ran on coal. “Coal happened. Railroads happened. People — many of them immigrants — poured into Appalachia. Roanoke was not the only boom town to spring up then. So did lots of other communities deeper in coal country.”

After an efflorescence during the last 70s/early 80s, coal went into decline. Mechanization eliminated jobs. Thicker, efficient-to-mine coal seams played out. Environmental regulations drove up the cost of mining and combusting coal. And natural gas began displacing coal in the utility market. As long as high-quality metallurgical coal used in steel making can be mined in Appalachia, mining will never totally disappear. But coal will be a shadow of the industry it once was.

Virginia’s coalfields have tried to diversity their economies, but they suffer enormous competitive disadvantages. They are geographically remote, far from large urban centers and interstate highways. They have a paucity of flat land suitable for industrial development. The workforce is poorly educated, substance abuse is widespread, and most ambitious young people who earn college degrees leave for better employment prospects elsewhere. And the quality of amenities and public services is low so that everyone who made significant wealth in coal mining moved out of the region. There is no moneyed business class to spark an entrepreneurial revitalization.

Some coal counties refuse to die. Wise County has been especially creative in trying to reinvent its economy around broadband, data centers and solar energy. Recent state legislation that would favor pumped storage as a complement to solar farms has Dominion Energy giving a serious look at the region. The economic impact of such a facility, if ever built, would exceed that of Dominion’s $1.8-billion Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center, which burns coal and biomass. But the economics of these dreams remain unproven.

“It’s hard to see what industries exist in which Appalachia has a comparative advantage as vast as it had in coal,” the Roanoke Times quotes economist Lyman Stone as writing. “I’m not saying none do or could ever exist; I’m just saying that if they can or do, they don’t seem extremely clear right now.”

In Stone’s estimation, without coal mining to prop up the economy, Appalachia’s population has a long way to fall. He writes: “We can’t let hopes blind us to realities. On some level, population must be associated with economic activity to support it. Coal mining is still declining, and when it’s completely gone, it’s not clear how much economic activity will remain, and therefore how much population can be sustained.”

Bacon’s bottom line: As much as I hate to acknowledge it, Stone’s prognosis is correct. The 21st century economy belongs primarily to populous urban areas. I wouldn’t discourage coalfield residents from trying to salvage their communities — indeed, I very much hope they succeed. But even if creative-thinking localities such as Wise succeed in diversifying their economies, data centers, solar farms and pumped-storage facilities employ very few workers beyond the construction phase. Such projects would bolster the local tax base, enabling counties to maintain basic services, so they are worth pursuing. But they won’t reverse the depopulation of the region.

The coalfield counties, like other remote, rural counties in Virginia, need to think how to decline gracefully. Hard-hit cities and towns in the Midwestern rust belt are learning how to cope with shrinking populations, and perhaps it’s possible to learn lessons from them. What rural counties do not need to do is invest scarce resources in desperate, long-shot bids to turn around their economies. The circumstances are dismal, but living in denial of economic reality will only make things worse.