Governor Northam delivers conventional wisdom to rural economic development conference.

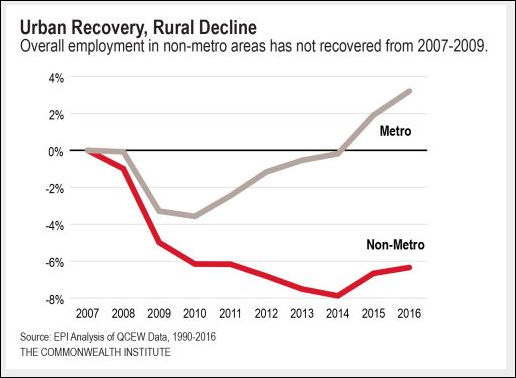

Despite the creation of 4,500 jobs in the “rural” portions of Virginia since he took office in January, Governor Ralph Northam told the Virginia Rural Summit yesterday that Virginia needs to do more to stimulate employment in rural areas.

Sounding familiar themes, Northam stressed STEM education, broadband access, and transportation. Twenty-first century jobs such as cyber-security and artificial intelligence require STEM education, the governor said, but young people don’t necessarily need to complete four-year college degrees. For some high-paying jobs, community college and certification programs may suffice. Rural Virginia also needs broadband access — within ten years, he said, as reported by the News Virginian. He also touted a recently unveiled, $2 billion plan to upgrade Interstate 81.

This is a familiar grab-bag of remedies, and it reflects the safe conventional wisdom on how to approach “rural” economic development. While improved broadband access indisputably would help “rural” economic competitiveness, it’s not clear at all that educating youth for “21st century jobs” or reducing congestion on I-81 will accomplish anything useful for “rural” communities. Northam’s address — like most of the discussion we hear — overlooks some unpleasant realities.

Let’s start by identifying what former blog contributor EM Risse refers to as a “core confusing word.” Near the top of the list of most obfuscating words used by planners and politicians is “rural.” It is impossible to have a rational discussion about “rural” development until we understand what we mean by “rural.”

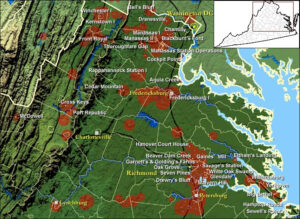

As commonly used by the Governor and others, “rural” refers to most of Virginia outside of the three main Metropolitan Statistical Areas — Washington/Northern Virginia, Richmond, and Hampton Roads. Depending on context, it may or may not include smaller MSAs such as Roanoke, Charlottesville, Lynchburg, Winchester, Staunton/Waynesboro, Danville, Bristol, Blacksburg/Christiansburg, and Harrisonburg. The term probably includes small mill towns such as, say, Galax, Halifax, Pulaski, Rocky Mount, and the former coal camps of Virginia’s “rural” coal-producing counties. However, the only areas we can be absolutely certain the term “rural” encompasses are the vast tracts of sparsely populated farms and woodlands outside the MSAs.

The economic assets and challenges faced by smaller MSAs, mill towns, and farmland/woodlands are very different. Likewise, the realistic expectations we can set vary widely depending upon a community’s particular assets and liabilities. Some key points:

The agglomeration force. The “agglomeration” force in a predominantly knowledge-based economy is incredibly powerful. Knowledge-intensive companies, which include almost all technology companies, gravitate toward urban areas with large, deep labor pools. As is vividly on display in Amazon’s selection process for its massive second headquarters, technology employers also seek urban areas with the kind of amenities — primarily walkable urbanism — that will enable them to recruit from outside the region and then to retain their employees.

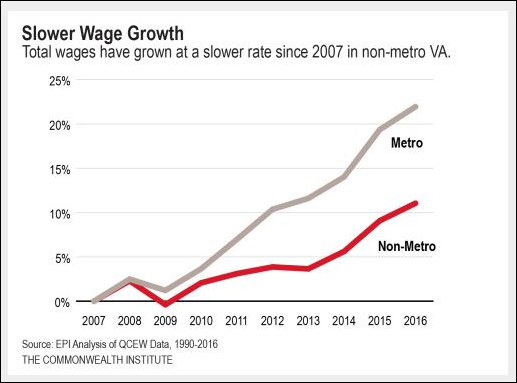

We can educate rural, small-town, and small-metro employees to participate in 21st-century knowledge-economy jobs, but they will find few employment opportunities outside the large MSAs. They will migrate to the large MSAs because that’s where the job opportunities are. Investing in educating “rural” young people for “21st century jobs,” whether in an expensive four-year college setting or a community-college setting, effectively subsidizes workforce development for the big, wealthy MSAs. If Virginia wants to create “rural” jobs, it needs to invest in occupations in which rural places and mill towns have a competitive advantage — which is not cyber-security and artificial intelligence.

Light manufacturing. Small-town Virginia continues to enjoy a competitive advantage in attracting light manufacturing, which requires cheap land, low taxes, and a supply of unskilled and semi-skilled labor. The problem is that manufacturing operations are subject to automation, which means that the yield in jobs from landing new manufacturing investment is smaller than in the past. As manufacturing gets more automated, we can expect fewer jobs but higher-skilled workforce needs from new projects. Manufacturing may be an area where an investment in community-college degrees and certifications may pay off — if the training is done in concert with the manufacturing companies to ensure that workers are learning relevant skills. How many manufacturing plants will need employees with certifications in cyber-security and AI, I have no idea. I’m guessing a few, but not many.

Transportation. The congestion on I-81 has virtually nothing to do with “rural” economic vitality. The highway links a string of small MSAs (Winchester, Harrisonburg, Staunton, Roanoke, Salem, Christiansburg, Bristol) and small towns. Just as big MSAs like Washington, Richmond and Hampton Roads have co-opted the Interstate highway system for local traffic, so have the small cities and towns along I-81.

I haven’t seen the plan for upgrading I-81, which has been described as involving widening and other improvements to be financed with some combination of gas tax, sales tax or tolls. But I feel confident about saying one thing: The improvements will be focused on increasing the capacity of the Interstate highway itself. It will not entail any changes to land use patterns or nearby non-Interstate transportation investments. Localities will continue to allow the clustering of development near I-81 intersections in a land-use pattern I call “rural sprawl.” Thus, they will perpetuate the use of the Interstate as a local transportation artery and accelerate the need for more improvements a couple of decades from now.

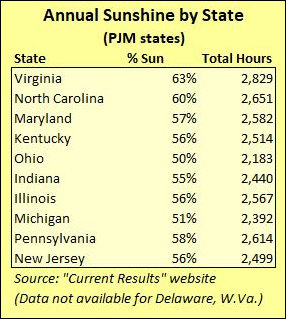

Rural/mill town/small MSA Virginia has two sustainable competitive economic advantages. One is a lower cost of living, which makes it potentially attractive to retirees who want to stretch fixed incomes. The other is raw physical beauty and access to recreational activities such as hiking, biking, canoeing, kayaking, sailing, ATV trails, and the like. Some communities also can build upon their local historical and cultural heritage. These assets can support retirement- and tourism-related industries. Whether such industries can support existing populations with decently paid jobs is problematic. Many rural/small town communities will have to learn how to deal gracefully with population decline.

Which brings me to a final point: How to deal gracefully with population decline. How do small and sparsely populated localities maintain a tolerable level of services and amenities when the population and tax base is shrinking? Not by subsidizing rural sprawl that drives up the cost of building and maintaining infrastructure. No one in Virginia is talking about this at all. But maybe, instead of squandering scarce resources on pipe dreams, “rural” Virginians and their political champions in Richmond should be giving this question more thought.