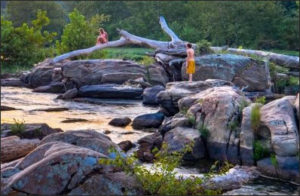

Downtown Abingdon, one of Virginia’s great walkable places.

The Roanoke Times tells a hard truth to the readers of Southwest Virginia: “Nobody cares about you.”

Democratic Governor Terry McAuliffe, says the Sunday editorial, has done nothing to help the counties of the far Southwest whose finances were devastated by the collapse of the coal industry. The Democratic Party in Virginia has “evolved into almost strictly a suburban-urban party that has no natural interest in anything west of the Blue Ridge.”

And the Republicans? After promising to help the coal industry, President Trump has proposed slashing funding for energy research and zeroing out a program that pays to convert old mines into industrial sites. Concludes the editorial:

What’s the takeaway from all this? We’re on our own. We cannot count on either Richmond or Washington to help us. Maybe from time to time one of them will come through with some unexpected grant to help with some piece of infrastructure and we should be grateful. On a day-to-day basis, though, it’s clear that both the state and federal governments have come to a bipartisan consensus: Southwest Virginia doesn’t matter to them.

What is the down-on-its-luck region supposed to do? Businesses need to get more engaged, says the Times. Local government needs to focus more on economic development. Voters need to be more demanding.

The Times is right. Other regions are indifferent to the fate of Southwest Virginia. They have their own problems and their own funding issues. Other regions insist that they’re getting a raw deal from the state. (Talk to a Northern Virginian some time. NoVa may be rich, but its citizens feel short-changed and aggrieved.) And every region pursues its own self interest. The bigger piggies muscle closer to the trough, leaving the weaker piggies behind. It’s Darwinism in a political setting.

Southwest Virginians would be well advised not to pin their hopes on the largess of others. What, then, can they do?

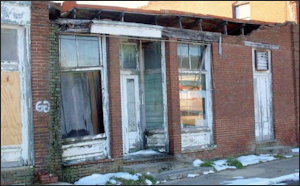

They could start by acknowledging some harsh realities. First, coal is never coming back. Natural gas, wind power and solar power are far cleaner and far cheaper. Economics will dictate than any new electric-generating capacity in the United States over the next decade will be either gas or renewable. Existing coal plants will serve out their economically useful lives, and then they will be phased out.

Second, manufacturing might rebound, but it will never provide the large-scale employment it did a generation ago. Some manufacturing operations may repatriate from overseas back to the U.S., and corporations will continue to invest in plant expansions. But robotics, artificial intelligence and other forms of automation mean that manufacturing processes will create require fewer and fewer jobs as time goes on. The return on investment on traditional economic development strategies — recruiting manufacturing investment — will continue to decline.

Third, the agglomeration economies of the Knowledge Economy will continue to favor metropolitan areas with large, diverse pools of skilled, educated labor over small, semi-skilled labor pools of rural communities. The Roanoke-Blacksburg area, with its access to Virginia Tech, its faculty, graduates and entrepreneurial spin-offs, conceivably can achieve economic escape velocity. But no other city or town in the region has that potential. Meanwhile, young people who succeed in obtaining a college education will continue to emigrate from the region — just like they’re doing in every other rural community across the country.

Making the challenge even more difficult, Southwest Virginia lacks an advantage possessed by other rural areas in Virginia such as the Shenandoah Valley, the northern Piedmont, and the Chesapeake Bay tidewater — proximity to large, affluent metropolitan areas. A location within easy driving distance of big metros will support an economy of resorts, vacation homes, retiree communities and weekend-getaway amenities for city dwellers.

What options does that leave Southwest Virginia? Not many. But the region is not destitute of assets. The Virginia Tobacco Region Revitalization Commission still has millions of dollars to dispense. The region just has to take care not to squander its limited resources on chimera like new Interstate highways, inter-city rail service, manufacturing subsidies, our outright follies such as government-supported golf courses, convention centers and other long-shot efforts to stimulate development.

I’ve written before about the Aspen model of economic development, built on active outdoor recreation — not just skiing but hiking, rafting, rock-climbing, mountain biking, kayaking, fishing, all-terrain riding, and so on — as well as a fabulous, walkable downtown. The walkable downtown is a critical element of Aspen’s success, and there is no reason that Virginia can’t replicate the formula in many of its small towns.

Call it the Abingdon model instead of the Aspen model. The town of Abingdon in Washington County is one of the most charming places in Virginia, and it is set in an area of great natural beauty. It has become destination that people are willing to travel hours to visit. Abingdon is proof that the strategy can work.

Wise County is another innovative community, exploiting its investment in broadband to recruit data centers. Data centers don’t support many jobs, but they do pay taxes that broaden the tax base. The county also is exploring opportunities to supply green energy to the data centers. Regional authorities should map the electric transmission grid, enact solar-friendly zoning ordinances and comprehensive plans, and encourage solar developers to consolidate properties capable of hosting utility-scale solar farms.

America is a big place, and while most rural areas (outside the fracking hotspots) are hurting. But some communities are faring better than others. Some are doing innovative things. Southwest Virginia can learn from the example of others. Perhaps it’s not a bad thing that no one else cares about the region. In the long run, dependence and handouts accomplish less than resilience and self reliance.