Bike lanes in Arlington County are not a parks & recreation sideshow — they create transportation options, reduce traffic congestion and promote healthy lifestyles.

Bike lanes in Arlington County are not a parks & recreation sideshow — they create transportation options, reduce traffic congestion and promote healthy lifestyles.

by James A. Bacon

The Arlington County Board takes bicycling very seriously. Every month, one or more members attend a planning staff update on the county’s bicycle program. They dig into the details. How many bike-share stations has the county installed in the last month? How many bicycle lanes have been striped?

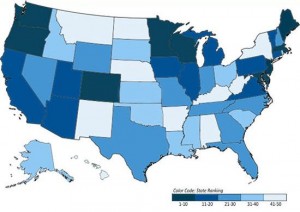

You don’t see that kind of high-level attention devoted to bicycle issues in many localities around the country. It helps that four of Arlington’s board members, including himself, are active cyclists, says Vice Chairman Walter Tejada. Board members also have a competitive streak. Arlington County received Virginia’s only “silver” ranking from the League of American Bicyclists’ 2012 listing of bicycle-friendly states and communities. But that wasn’t good enough. “We have a little chip on our shoulder,” says Tejada. “We want to be gold.”

The commitment to cycling runs deeper than winning kudos, however. It dovetails with the county’s Fit Arlington campaign to promote public health. And it is integral to the county’s plan to develop “complete streets” that accommodate pedestrians, bicycles and mass transit as well as cars. A top county priority is to reduce the number of cars on local roads, ameliorate congestion and improve livability. More bikes on the road means fewer cars.

Bicycling for every-day transportation, not just recreation, has great untapped potential in Arlington, says Dennis Leech, county director of transportation. Bicycles’ share of trips is relatively low, around one or two percent. “Over the past two or three years, there has been a real push to raise awareness, with the intent of getting that bicycle travel share up to five to ten percent.”

Across much of Virginia, bicycles are seen as transportation frivolity, simply not to be taken seriously. The federal government may require the state to spend money on bicycle trails but hardly anyone rides them, the thinking goes. Siphoning away money from roads to serve a tiny percentage of Sunday riders or spandex-clad racing nuts doesn’t make sense. The indifference of elected officials is reinforced by an outright hostility among some motorists who regard bike riders as pests taking up road space, clogging traffic and creating safety hazards.

But the bicycling movement is gaining momentum elsewhere in the Old Dominion, most notably Richmond, Roanoke and college towns like Charlottesville, Blacksburg and Harrisonburg. Cities and urbanized counties contemplating bike-friendly policies have a lot to learn from Arlington, which has ridden farther down the bicycle trail than other Virginia localities.

Some key lessons from the Arlington experience:

- Build a network. If you want to create a bicycle-friendly community, you have to go “all in.” A biking path here and a bike lane there don’t add up to anything useful. Just as motorists need a network of roads to drive between home, work and shopping, cyclists require a network of lanes to reach a wide range of locations.

- Support the biking culture. Cyclists need racks to park their bikes. They need lockers and showers to make themselves presentable for work. Communities need to educate citizens about bikes as a transportation option and promote safe cycling.

- Understand the payback. While cyclists don’t pay user fees like gasoline taxes, they do create economic value. Localities that are rich in travel choices enjoy higher property values than those where travel is limited to automobiles. Higher property values translate into higher property tax revenues. Moreover, by taking cars off roads, bicycle-friendly policies can reduce or defer spending on auto-oriented infrastructure from roads to parking spaces.