Driving live stakes into the eroding bank of Westham Creek.

Virginia’s suburbs are hard on water quality and wildlife habitat. You can do something about it. Create a neighborhood preserve and get to work!

by James A. Bacon

If everyone swept their front stoop, the old saying goes, the whole world would be clean. With that philosophy in mind, two or three dozen volunteers with the Countryside Homeowners Association mobilized Saturday to clean up the creek running through their neighborhood. In a morning’s work, they collected several bags of trash, planted roughly 500 dogwood and willow stakes along the eroded stream bed, and built “rabbitats” to make homes for small woodland creatures.

Countryside homeowners had long ignored the stretch of Westham Creek running through the neighborhood. Once in a while, someone would call the public works department when culverts got clogged and the creek backed up, and occasionally kids would play in the woods, but that was about the extent of it. Over the 11 years I’ve lived in the subdivision, I paid little heed to the creek, which does not touch my property. But my environmental consciousness is more expansive these days than in years past, and my thoughts have turned increasingly to the forlorn and neglected strip of woods running through my neighborhood.

Indeed, you could say that I have become a zealot on the subject. I heartily urge other Virginia homeowners to undertake the clean-up of the creeks and streams in their own back yards, and I offer this article as a modest example of what citizens can accomplish on their own. There is no need to wait for the James River Association or the Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay to come organize you. In the immortal words of the Nike commercials, just do it!

My enthusiasm was kindled a few months ago when Barbara Brown, president of our homeowners association, shared a consultant’s report that she had commissioned at her own expense regarding the potential for creating a neighborhood wildlife sanctuary. The report concluded that the Westham Creek floodplain was of sufficient size and quality to serve as a viable conservation area, providing “green space for residents to enjoy, quality wildlife habitat, water quality protection benefits and … an educational starting point for many community activities.” The potential existed, the consultant said, to create a communal asset that would “interest prospective home buyer as properties changed hands over the years.” In other words turning the floodplain into a neighborhood asset could increase property values.

Legal title to the land in the flood plain had been held by the Countryside Corporation, which had developed the subdivision. Taking ownership itself, the homeowners association created a conservation area that benefited everyone and made it easier to get the neighborhood excited about its upkeep and maintenance.

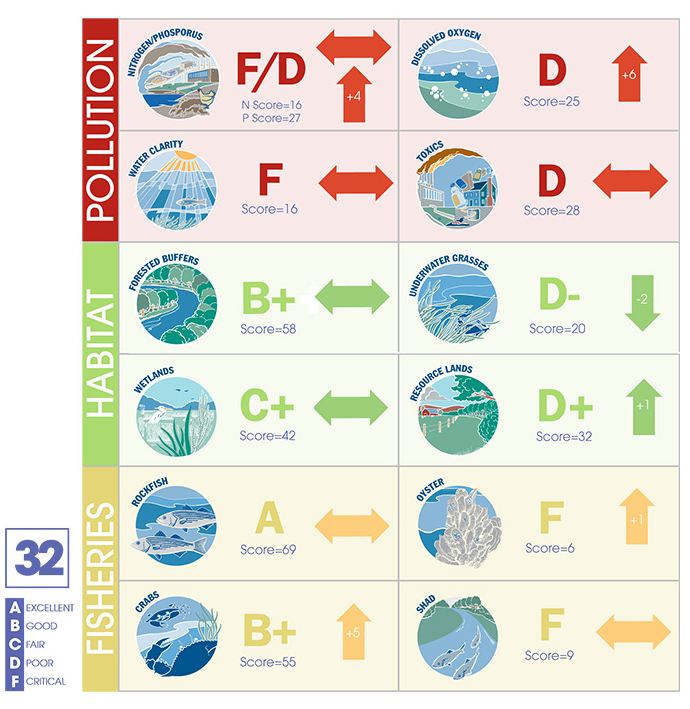

Around the time that I became aware of Barbara’s initiative, I had been writing about stream and creek restoration efforts in the James River watershed as part of a wider effort to clean the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. Much of the Bay pollution comes from everyday activities of suburbanites like my neighbors and me. We fertilize our lawns with little thought to the nitrogen and phosphates that wash into our creeks, flow downstream and ultimately create algae blooms and dead zones in the Bay. We neglect the neighborhood creek, only dimly aware that erosion washes tons of sediment into the river, clouding the water, blocking sunlight and killing underwater grasses so vital to Bay and riverine ecosystems. We are a part of the problem. But with a little effort we can be part of the solution.

Barbara was organizing the neighborhood’s first spring clean-up event, so I volunteered to see what could be done to fix our stream. I took John Newton, Henrico County’s stream-reclamation engineer, on a tour of Westham Creek, showing him where the stream had cut stream banks as high as six feet and had washed away the soil from under towering trees, leaving tangles of exposed roots. Newton said the erosion was pretty bad but had not reached a level where it justified county intervention. He recommended that we stabilize the creek banks by planting live stakes every few inches, three rows high, in a diamond-shaped pattern. Within a couple of years, the stakes would grow into dense foliage with thick mat of roots that should hold the soil into place.

The next step was figuring out where to find the live stakes. The stakes are a specialty product, cut in uniform lengths of about two feet, stripped clean and chopped diagonally at one end for easier insertion into the sand and clay. The James River Association put us in touch with Ernst Conservation Seeds, of Meadville, Pa., which specializes in bioengineering and wetlands materials. For about $500, which the homeowners association paid for, Ernst shipped us roughly 500 stakes of Red Osier Dogwood and Black Willow.

Now, I know next to nothing about planting live stakes. But I had read a couple of pamphlets and talked to a couple of experts when writing my articles. And in the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king. So, while Barbara supervised the trash clean-up and rabitat construction, I organized the stake-driving team.

It was a nippy March morning. A dozen men and a couple of teenage boys spent a couple of hours splashing through the (mostly) shallow creek and pounding stakes into the riverbank. We had enough material to stabilize about 40 to 50 linear yards. The key was to drive in the stakes at a such an angle and depth for their roots to tap the water. Having absolutely no idea of what we were doing, we will have to wait and see how many live and how many die. Hopefully, we will learn enough from our floundering exertions that we can repeat the process more successfully next year on another stretch of creek bank. The creek has enough erosion to give us spring projects for years to come. Read More.

Carpetbagger. Bob Goodlatte is the 13-term congressman from Virginia’s 6th Congressional District who has blessedly chosen to retire this year. In my opinion he represents just about everything that is wrong with the GOP. Born in Holyoke, Massachusetts and educated at Bates College in Maine, Goodlatte somehow avoids the “carpetbagger” moniker so quickly put on Terry McAuliffe by Virginia’s Republicans. He won his congressional seat at age 39 and has spent the last 26 years in Congress. Yet he goes uncriticized as a “politician for life” by the conservative Newt Gingrich types who claim to eschew such long running elected officials. He is a polluter’s best friend with apparently no concern for the property rights of those negatively affected by the pollution he justifies and defends. However, he’ll be gone soon and you’d think we’re past the damage done by this phony conservative. Oh no. Even in his final days in office Goodlatte is actively denying people protection of their property rights despite “property rights” supposedly being a core tenet of conservative Republican dogma. What a farce.

Carpetbagger. Bob Goodlatte is the 13-term congressman from Virginia’s 6th Congressional District who has blessedly chosen to retire this year. In my opinion he represents just about everything that is wrong with the GOP. Born in Holyoke, Massachusetts and educated at Bates College in Maine, Goodlatte somehow avoids the “carpetbagger” moniker so quickly put on Terry McAuliffe by Virginia’s Republicans. He won his congressional seat at age 39 and has spent the last 26 years in Congress. Yet he goes uncriticized as a “politician for life” by the conservative Newt Gingrich types who claim to eschew such long running elected officials. He is a polluter’s best friend with apparently no concern for the property rights of those negatively affected by the pollution he justifies and defends. However, he’ll be gone soon and you’d think we’re past the damage done by this phony conservative. Oh no. Even in his final days in office Goodlatte is actively denying people protection of their property rights despite “property rights” supposedly being a core tenet of conservative Republican dogma. What a farce.