by James A. Bacon

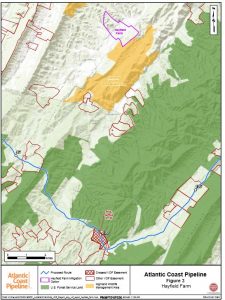

A poll commissioned by the Chesapeake Climate Action Network shows strong public opposition to the Atlantic Coast Pipeline and strong support for tougher restrictions on the disposal of coal ash.

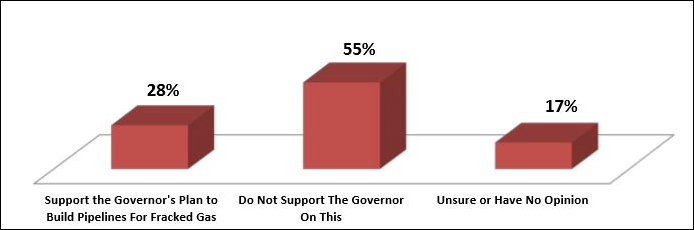

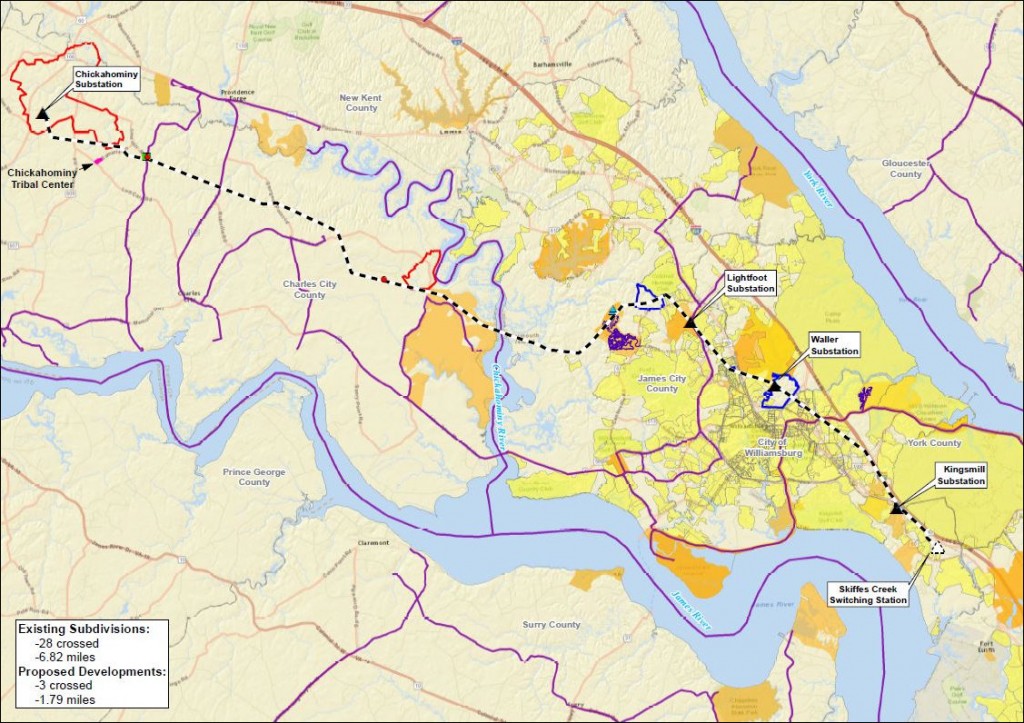

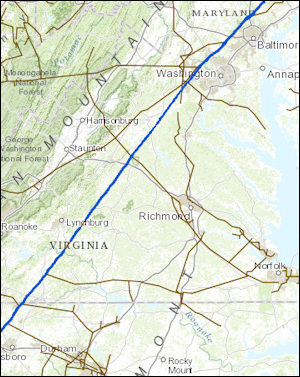

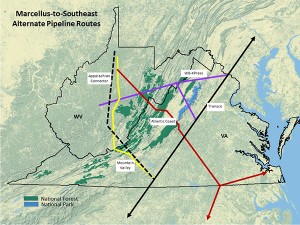

Twenty-eight percent of Virginia voters support Governor Terry McAuliffe’s backing of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline and the Mountain Valley Pipeline while 44% oppose it, found a poll conducted by the Cromer Group in a run-up to a planned picketing of the governor’s office in October.

Meanwhile, 71% of voters polled said McAuliffe should follow the example of other southern states by requiring coal ash to be deposited in lined landfills rather than buried in place near rivers.

“This poll shows that Governor McAuliffe’s cheerleading for fracked-gas pipelines is not only dangerous for communities and the climate, but decidedly unpopular in Virginia,” said Mike Tidwell, director of the Chesapeake Climate Action Network in a press release. “The Governor likes to dismiss both the pipelines and coal ash as ‘federal issues’ beyond his influence, but that’s untrue. He has direct executive power to act on behalf of Virginians facing direct harm now. Governor McAuliffe has the means and the moral responsibility to reject the pipelines and to reform coal ash disposal, and his legacy depends on it.”

Bacon’s bottom line: This poll of 732 registered Virginia voters asked two questions. The questions were not laughably slanted, as in some push polls I’ve seen.

(A great example is a American Civil Liberties Union poll sitting on my desk that I actually may respond to, just for yuks. Sample question: “Across the country, we’re seeing efforts to twist the meaning of religious liberty to allow people and businesses to use religion as a license to discriminate and a means to impose their religious beliefs on others. How serious a problem do you think the use of religion to discriminate is in our country today?”)

Though the Cromer Group questions don’t sink to the level of the ACLU’s risible push poll, that’s not to say the phrasing of the questions didn’t nudge respondents toward the desired answers. The first question reads as follows:

Governor McAuliffe supports building two long pipelines that would bring gas from West Virginia into Virginia and send it across the state. He says the pipelines will create jobs, lower bills, help manufacturing, and help the environment. This gas would be extracted through hydraulic fracturing drilling, or fracking. Opponents say these pipelines will allow energy corporations to take hundreds of miles of privately owned land from citizens for private corporate gain. Opponents also say the pipelines will harm Virginia farms, worsen pollution, and damage drinking water and local wells. Weighing the pros and cons, do you support the Governor’s efforts to build these pipelines for fracked gas across Virginia, or not?

The statements within the question are accurate, or at least arguably so. The questions do not contain obviously biased language. They mention reasons to both support and oppose the pipeline. However, the question devotes only 14 words to the “pro” side while giving 41 words to the “con” side. In addition, it refers twice to “fracking” and “fracked gas,” which one could argue are loaded phrases.

Here is the second question:

For decades, Dominion Power has burned coal to create electricity, resulting in an accumulation of millions of tons of coal ash waste near the banks of the Potomac, James, and other rivers. This waste must now be disposed of. Dominion wants to leave its coal ash waste in the ground, covering the top of the ash and not placing protective barriers or linings along the bottom. Dominion says this is safe. North and South Carolina and Georgia have rejected this method as unsafe. They have required the coal ash be moved away from rivers and drinking water into protected, lined landfills. Do you think the Governor should support Dominion’s approach, OR, follow the example of other Southern States to remove the ash to modern landfills?

Again, the statement is accurate and it contains no loaded language. Yet it frames the issue in such a way as to ask the respondent, who likely has no independent knowledge to draw from, to choose between believing Dominion or believing three state governments regarding the best way to dispose of coal ash. The question clearly leads the respondent to group’s preferred answer.

That’s not to say that the question is illegitimate. Virginians should take into consideration the regulatory approaches of other states when pondering how best to regulate coal ash in Virginia. But that is only one way to frame the question. Alternatively, the poll could have focused respondents on the cost of the coal ash disposal. Dominion has estimated the bill could total $3 billion. Environmentalists say it would cost less. I dare say that a question focusing on cost would have yielded different results.

Are those biases in the questions sufficient to skew the findings? Is this a poll that Governor McAuliffe should take seriously? Now that I’ve biased you with my analysis, you tell me. Please respond in the comments section.

Update: Dominion spokesman David Botkins has issued the following statement: “Dominion’s plans for closing coal ash ponds as well as building the ACP protect the environment. To say otherwise is untrue. Over the last many months Dominion has developed plans to close our ponds by consolidating the ash on station property. EPA endorses that approach. The poll is an obvious effort to use biased questions based on incorrect information to slant the results.”