A federal judge has dismissed a lawsuit filed by landowners seeking to block the Atlantic Coast Pipeline (ACP) from surveying their land for the purpose of building a pipeline.

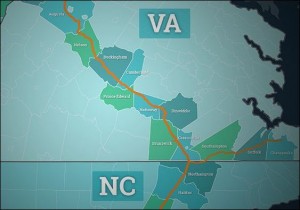

Three landowners in the path of the proposed 550-mile project had challenged the constitutionality of a state law permitting the pipeline to survey their lands, as long as it abode by certain formalities of notification. After filing the suite, ACP altered the proposed route to bypass the properties of the three plaintiffs.

“The court concludes that the plaintiffs’ facial challenges to the statute fail because the statute does not deprive a landowner of a constitutionally protected property right,” wrote Elizabeth K. Dillon, with the U.S. District Court in Roanoke. Additionally, Dillon ruled, the challenges fail because they are not “ripe,” that is, they are abstract and hypothetical now that ACP has announced that it no longer intends to survey their property. The plaintiffs “face no immediate threat of injury.”

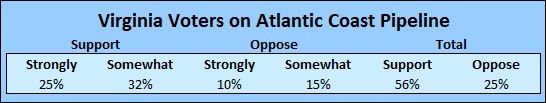

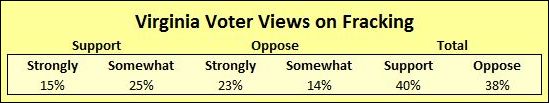

The ruling removes another legal obstacle to surveying and ultimately constructing the pipeline, which its owners, including managing partner Dominion, say will help meet the growing demand for natural gas in Virginia and North Carolina as electric utilities substitute natural gas for coal. In theory the plaintiffs can appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, although it is not clear if they intend to do so.

In an email response, Charlotte Rea, one of the plaintiffs and co-chair of the “All Pain No Gain” group opposing the pipeline, stated the following:

As you might expect, I am disappointed. I don’t think our forefathers when they wrote the Constitution expected its interpretation to allow for private investor owned corporations to violate the property rights of private citizens. The Constitution only allows for private property to be taken if it is for proven public need and just compensation is provided the landowner. Surveys by private corporations on private property should not be allowed. There has been no determination made that the Atlantic Coast Pipeline project is for the public good. Until that determination is made, private property owners should not have to cede any property rights.

In a press release, Dominion stated:

From the beginning, we have always believed that the Virginia law is consistent with the U.S. Constitution and allows surveys with proper notification and landowner protections. Yesterday’s ruling affirmed that belief and our actions.

ACP has followed the procedure as laid out in the Virginia law to survey the best route with the least environmental impact. The Virginia law allows survey only as necessary to meet regulatory requirements.

The plaintiff’s attorneys argued that the Takings clause of the Constitution protects property rights, specifically the right to exclude — to forbid others from trespassing. However, wrote Dillon, common law has long recognized that the right to exclude is not absolute. “Courts also have long recognized the common-law privilege to enter private property for survey purposes prior to exercising eminent domain authority.”

Consistent with the common law, Virginia has long permitted governmental entities to conduct surveys on private property before exercising eminent domain authority. For instance, Dillon wrote, the Code of 1819 gave a turnpike company “full power and authority to enter upon all lands and tenements through which they may judge it necessary to make said road.”

Foes have questioned whether the Atlantic Coast Pipeline provides a public purpose, given that it is one of four pipelines proposed to run through Virginia and that pipelines are being built to serve New York and nearby markets, freeing up capacity by the existing Transco mega-pipeline serving Virginia.

However, Dillon wrote:

In the Natural Gas Act, Congress ‘declared that the business of transporting and selling natural gas for ultimate distribution to the public is affected with a public interest.’ … [The Virginia survey law] allows a natural gas company to gather … information required for the certificate by giving it the ability to enter property and conduct a minimally invasive survey. The statute thus facilitates the ‘transportat[ion] and selling’ of natural gas, and thereby serves a public purpose.”