by James A. Bacon

When last I blogged about Richmond Pulse, the Bus Rapid Transit plan for the city’s Broad Street corridor, the projected cost had leaped $11.5 million over its original $50 million estimate. While I support mass transit in the right circumstances, I saw little good coming from this project, in which state and federal authorities had helicoptered dollars upon the Greater Richmond Transit Company (GRTC) and the city had done little to create the conditions — zoning for appropriate land use, funding streetscaping and planning for intermodal connectivity — needed to make the project a success.

I was worried that I might have offended my old buddies in the local Smart Growth community by my unsparing criticism of the transit project. As it turns out, I need not have worried. They shared the same concerns. Indeed, they have been working feverishly through the planning process to correct the obvious deficiencies.

“Typically plans for transit projects sit on the shelf for years while agencies try to find funding,” says Trip Pollard, an attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center, “but in this case, while some planning certainly had been done, the funding got ahead of the planning.”

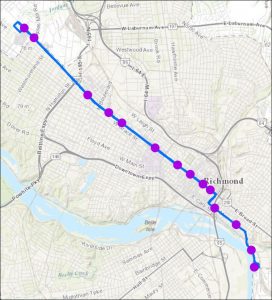

The project, which runs 7.6 miles from Rocketts Landing at the east end of the city to the Willow Lawn mall at the west end, is scheduled for completion in the fall of 2017. Planners have moved into high gear trying to catch up. Two important studies should be complete this fall.

The Richmond Regional Transit Vision Plan will create a regional transit vision plan to stakeholders and the public that will guide transit development in the region through 2040. The idea is for Pulse to be part of a more comprehensive regional transit system.

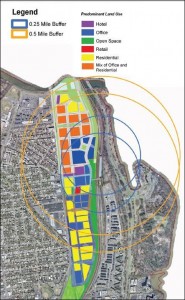

The Broad and East Main Street Corridor Plan will focus on the Pulse corridor, identifying where development should occur, what development should look like and how it should happen.

Meanwhile, the Richmond Transit Network Plan will rethink the design of the city’s bus network in the context of Pulse. For example, will Pulse free up GRTC resources to improve service on other routes? How can regular bus routes interface with Pulse? Can GRTC optimize its bus service in other ways? Jarrett Walker + Associates, renowned for its re-engineering of the Houston bus system, will conduct the study. That should be complete next year.

As a bonus, the U.S Department of Transportation is providing technical assistance in the Ladders of Opportunity Transportation Empowerment Pilot Initiative to promote Transit-Oriented Development in the low-income Fulton community, whose residents are expected to use the BRT to reach jobs in the West End.

While implementation of the Pulse project has not exactly risen to a top-of-mind issue in Richmond’s highly competitive mayoral race, “there is a mobilized civic community,” says Stewart Schwartz, executive director of the Coalition for Smarter Growth. Civic leaders are determined to make sure the project is done right.

The Smart Growth community has a lot riding on this project. If Pulse crashes and burns, it will undermine political support for more mass transit funding in the Richmond region. Conversely, if the project is successful, it could pave the way for a regional system.

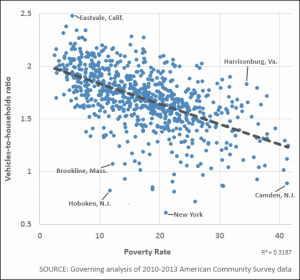

Income: Poorer communities, or those with large concentrations of poverty, tend to have more car-less households and fewer cars per family. These households are more likely to car pool or avail themselves of whatever non-car alternatives exist, typically municipal bus systems. As the Governing scatter chart to the left shows, there is a significant correlation between the poverty level and the vehicle-to-household ratio. Note: Governing identified Harrisonburg as an “outlier” having both a high poverty rate and high rate of auto ownership.

Income: Poorer communities, or those with large concentrations of poverty, tend to have more car-less households and fewer cars per family. These households are more likely to car pool or avail themselves of whatever non-car alternatives exist, typically municipal bus systems. As the Governing scatter chart to the left shows, there is a significant correlation between the poverty level and the vehicle-to-household ratio. Note: Governing identified Harrisonburg as an “outlier” having both a high poverty rate and high rate of auto ownership.