by James A. Bacon

The impact of the COVID-19 virus in Virginia varies widely by age and medical condition, afflicting some groups far more than others. That foundational reality gave rise to a key principle, which, I suggested four days ago, should guide Governor Ralph Northam as he deliberates about how, and how fast, to roll back his emergency shutdown measures: Public action should focus on protecting the most medically vulnerable members of society while allowing the least medically vulnerable to return to normal life and work as quickly as possible.

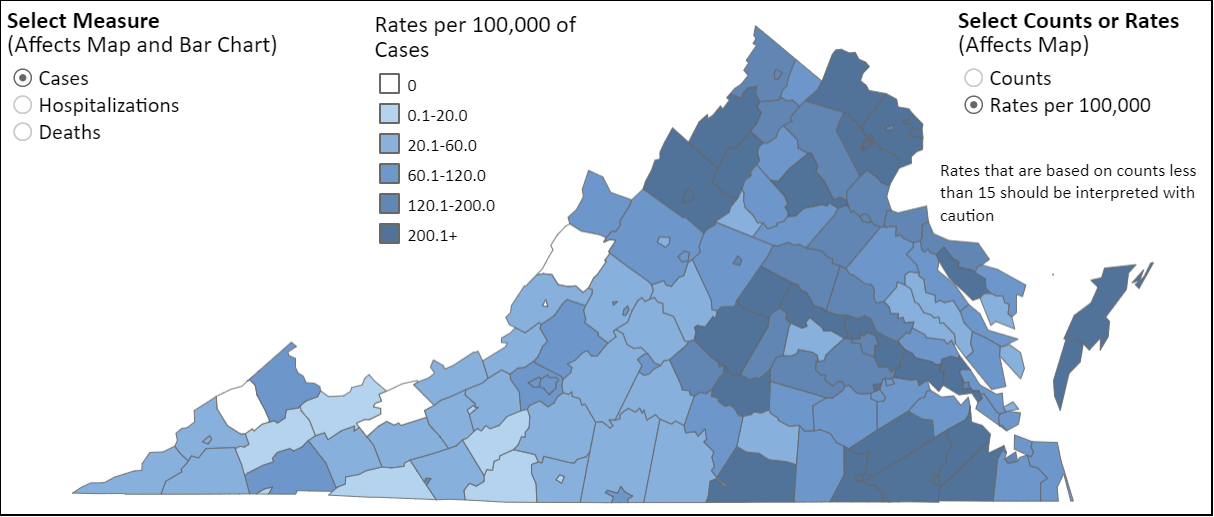

Today I explore a second principle: Recognizing that the virus is far more prevalent in some regions of the state than others, emergency restrictions should be tailored to the unique conditions of each region. Measures that are suitable for Arlington (1,106 confirmed cases) are not suitable for Dickenson County (zero confirmed cases).

The map above, taken from the Virginia Department of Health COVID-19 dashboard, shows the incidence of the virus per 100,000 population. (Click here to view the interactive map directly and view the data for each locality.) The virus has penetrated the population of the eastern half of the state to a much greater extent than the western half. Virginia’s Appalachian counties in Southwest Virginia, especially those off the Interstate 81 corridor, have barely been affected.

It is legitimate to ask, as several Southwestern legislators have, why draconian lockdown standards that may (or may not) be appropriate for the eastern part of the state should apply to western Virginia where the disease is far less widespread yet the economic pain is just as prevalent. Why kick these counties when they’re down?

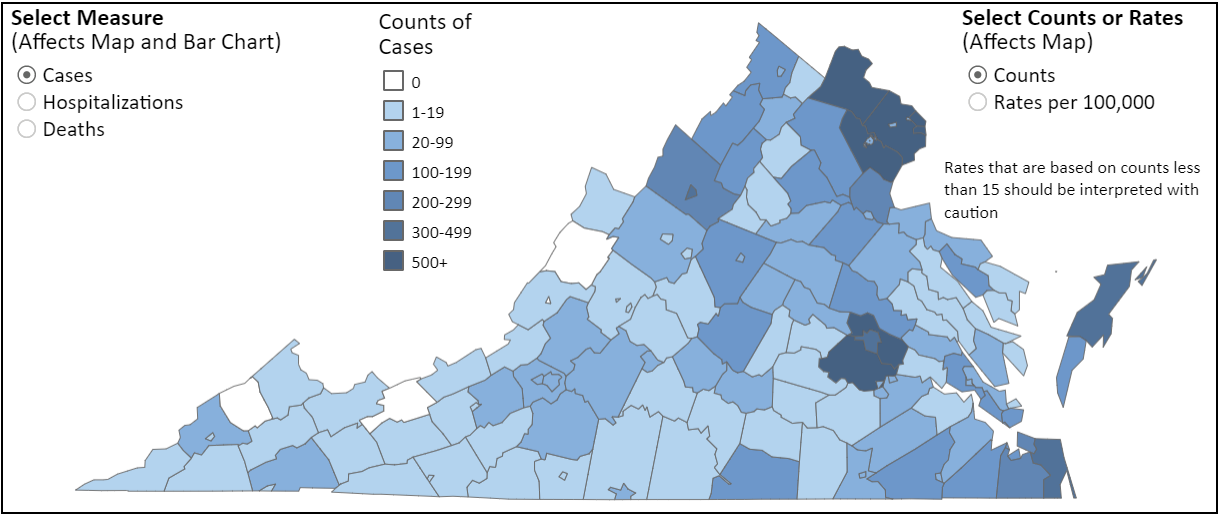

This map shows the rate of hospitalizations per 100,000 population. The differences between highly impacted and less impacted regions of the state is even starter. By this measure, COVID-19 is a problem mainly for Northern Virginia and the Richmond metro, and to a lesser degree Hampton Roads and the Northern Shenandoah. The trade-offs between saving lives and saving jobs is very different in each case.

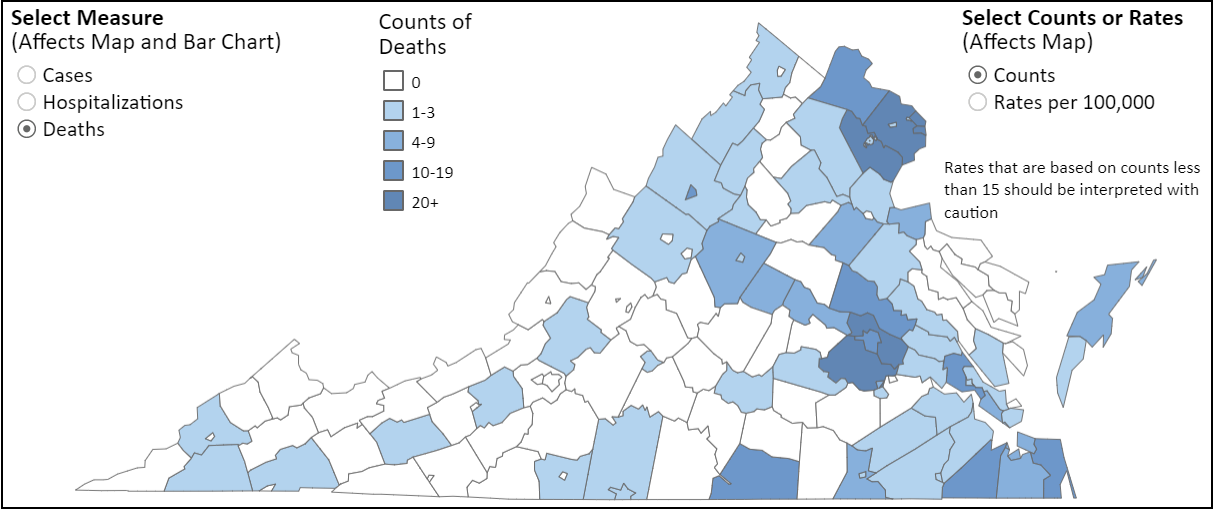

Finally, this map shows the rate of deaths per 100,000 population. Large swaths of the state, mostly rural, have seen no COVID-19 deaths at all.

Fewer confirmed cases, fewer hospitalizations, and fewer deaths. Treating the localities in the low-incidence zone the same as in Northern Virginia and metro Richmond seems almost punitive. Maintaining statewide standards regardless of local conditions shows either an excessively rigid mindset or a near-criminal indifference. Or maybe both.

Let us recall the original justification for the emergency measures. The purpose was never to snuff out the virus, an impossibility in the absence of a vaccine, but to “flatten the curve” so that the health care system was not overwhelmed by an influx of patients. Well, it turns out that in Virginia’s rural areas and small towns that the curve flattens naturally all by itself. I’ll leave it to the epidemiologists to make authoritative statements about why that might be, but I’ll suggest that it is tied to a number of factors such as: (1) lower use of mass transit, (2) fewer buildings with elevators, (3) greater spatial distancing between residences, and (4) less travel in and out.

I’m not arguing that all restrictions be dropped. A larger percentage of the population in western Virginia works in factory settings where the disease can be more easily transmitted. It may make sense to require manufacturing operations to hew to higher-than-normal standards of hygiene. Many employers are already adapting to the world of COVID-19 by making voluntary changes. But not everyone gets the message, and it may be appropriate to ensure that everyone does.

But I am saying that the emergency restrictions should be tailored to the local facts on the ground, and should be no more onerous than absolutely necessary. A failure to make such accommodations will bring needless economic devastation to parts of the state that already had the economic odds stacked against them. No number of feel-good bandwidth initiatives and workforce training programs can make good for the damage inflicted by the shutdown.