Around America, there’s a boom in solar energy. More solar power generation was installed in 2015 than ever before and 2016 could be even better, doubling in U.S. solar capacity. Although solar still provides less than one percent of America’s total electricity, it’s the fastest growing source of new energy since shale gas.

The benefits of solar are clear, from energy independence and greenhouse gas reduction to money savings and job creation to attracting high-tech industries.

But Virginia, which ranks a pitiful #30 for installed solar capacity, far behind neighboring states, including Tennessee at #18, Maryland at #13 and North Carolina at an impressive #3, is not seeing these benefits.

The state consistently ranks near the top in desirable industries from software and cybersecurity to higher education and even wine, yet the Old Dominion ranks in the bottom half of US states for solar power. Why?

It’s not lack of sunshine. If southern sunshine were required for solar power to thrive, then New Jersey, New York and uber-Yankee Massachusetts would never have made it to the list of the top ten solar states.

Nor does Virginia lack demand for clean electricity, especially from one of the state’s most promising high tech industries, the data centers of northern Virginia that host 70% of the world’s Internet traffic. Apple, Google, Facebook and other companies have committed to get 50% or more of the power for their server farms from renewables. In Virginia last year, Amazon.com commissioned what will be the largest solar array in the state, an 80-megawatt plant to be located on the Eastern Shore, to provide itself with clean power.

Finally, while Virginia’s average rates for grid electricity are certainly among the nation’s lowest, southeastern states that have utility power rates comparable to ours have much more solar than we do, including both North Carolina and Tennessee, as well as Georgia (ranked 11th).

None of these traditional explanations makes sense for a relatively wealthy state like Virginia (ranked 12th nationwide for gross state product) to fall into the bottom half of U.S. states for solar, in the company of much poorer states such as Arkansas, Alabama and Mississippi.

The obvious difference between Virginia and comparable states with much more solar? Public policy.

Given the 50% decrease in the cost of solar panels over the last five years, solar power no longer needs taxpayer subsidies to flourish. What solar does need is a market free of restrictions that do not serve the public interest and only serve to protect utility market share from competition.

“Solar can certainly compete in a level playing field with other energy forms, and already we are offering solar electricity at less than the cost of grid electricity for our schools, universities, churches and hospitals in Virginia, without any grants or state subsidies,” says Anthony Smith, CEO of the largest solar developer headquartered in the state, Staunton-based Secure Futures. (Full disclosure: I am a former employee of Secure Futures. The company has been a client of my marketing agency, but not for two years).

“At the same time,” says Smith, “it’s very hard to compete with regulated electric power companies that get a guaranteed 10% return on investment paid by rate-payers for every dollar they spend on polluting energy sources and lobbyists, and virtually every activity in between.”

Smith and other solar company leaders in Virginia aren’t asking for more subsidies. Instead, they just want the freedom to sell solar power to customers as solar companies can in states with less restrictive rules.

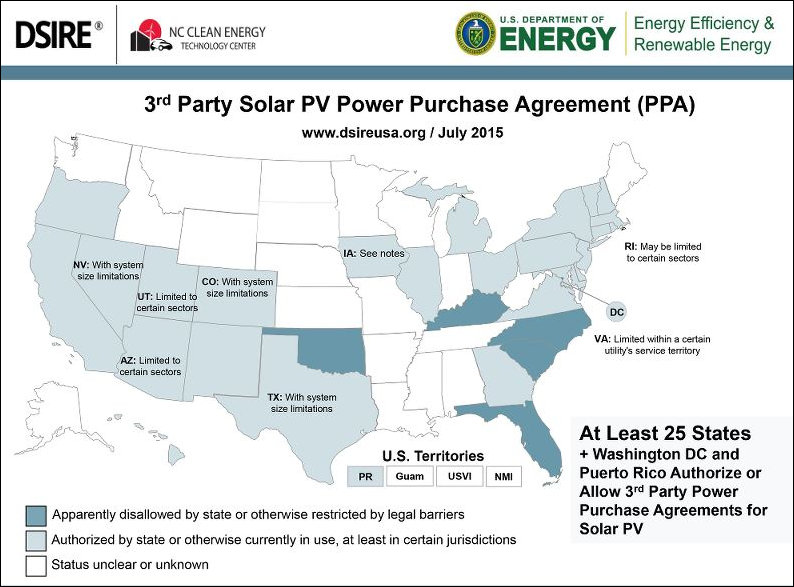

Above all other policies, the one that Smith thinks would help Virginia the most would be to allow allow power-purchase agreements (PPAs) for solar across the state and across the board. Currently, Virginia’s pilot PPA program passed by the general assembly in 2013 only allows solar companies to sell power directly to large-scale solar customers (but not to homeowners) and only within the service area of Dominion Virginia Power.

Solar PPAs are widely used in twenty or so states, and letting homeowners in on the game has helped make states like Maryland and North Carolina into solar leaders. PPAs are so revolutionary because they allow homeowners, businesses and local governments to get solar at no-money down, removing the high initial cost that’s the main barrier to adopting solar power.

In a PPA, a solar company installs panels on the customer’s property, but retains ownership of the equipment. The company then sells the power to the customer below the cost of power from the grid, so that the customer saves money over the period of the PPA, generally 10-25 years. Afterwards, the customer can get the panels at a discount or at no additional cost.

For decades, utilities have long used PPAs to buy power from each other, especially in periods of high demand. In Virginia, Amazon will use a PPA to get the power from the big solar plant on the Eastern Shore developed by Community Energy, Inc., and purchased by Dominion.

So, Dominion and other utilities seem to like PPAs just fine for their own use. But utilities are somewhat less enthusiastic about allowing solar companies to sell power under PPAs. Utilities argue that, for the benefit of ratepayers, not just anybody should be allowed to sell power in a regulated environment.

Somehow, though, in states with widespread use of solar PPAs, the grid hasn’t collapsed and power rates haven’t spiked.

The solar industry argues that Virginia restricting PPAs is just a form of protectionism for utilities, which have great influence in the general assembly.

The solar array that Secure Futures is building now at the University of Richmond will be the state’s first solar project by a non-utility company to operate under a PPA. Smith wants to see other companies follow his example.

“The number #1 thing that needs to change for increasing solar in Virginia is to create more freedom of choice” for energy consumers, says Smith.

In the long run, that might involve decoupling utility profits from power generation. In that way, utilities could still make money even if solar companies sell power in their service area. In the short run, given their success in neighboring states, allowing wider use of PPAs is a policy that Virginia should adopt to catch up with other states on solar at no cost to taxpayers.

Erik Curren runs the Curren Media Group, a Staunton-based digital marketing agency serving industries including solar power.