Richmond has been awarded the dubious distinction of being the “sneeziest and wheeziest” city in the United States in a report issued yesterday by the Natural Resources Defense Council. And thanks to global warming, says the NRDC, conditions are likely to get worse.

Scientific studies have also shown that our changing climate could favor the formation of more ozone smog in some areas and increase the production of allergenic pollen such as that released by the ragweed plant, the principal source of pollen associated with allergic rhinitis. This is bad news for allergy sufferers and asthmatics because both ragweed pollen and high levels of ozone smog can trigger asthma attacks and worsen allergic symptoms in adults and children.

Richmond, as it happens, suffers from both high ozone and high ragweed counts. As the report notes, Richmond was was named the 2014 top U.S. Asthma Capital by the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America (AAFA. “Contributing to Richmond’s status as the number one Asthma Capital are high pollen levels, death rates from asthma, and numbers of asthma-related emergency room visits.”

As temperatures slowly ratchet higher, one would conclude from the parade of horribles revealed by study after study like this one that a warmer climate heaps nothing but harm harm and misery upon mankind. No doubt that explains why Americans have been migrating en mass from southern states to northern in search of cooler temperatures. … Oh, what’s that? It’s the reverse? Americans are migrating to states with warmer temperatures? Does not compute.

Permit me to play devil’s advocate. The NRDC may be absolutely correct in its appraisal but, at the risk of being denounced once more as a “climate denier,” it can’t hurt to subject its claims to some critical analysis.

The NRDC makes this interesting statement:

Richmond, Virginia, is—for the second time in a row—number one on this list. Although Richmond does not have an ozone monitoring station and is not ragweed-positive, we include it on the map because of its status as the number one Asthma Capital, as published by the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America.

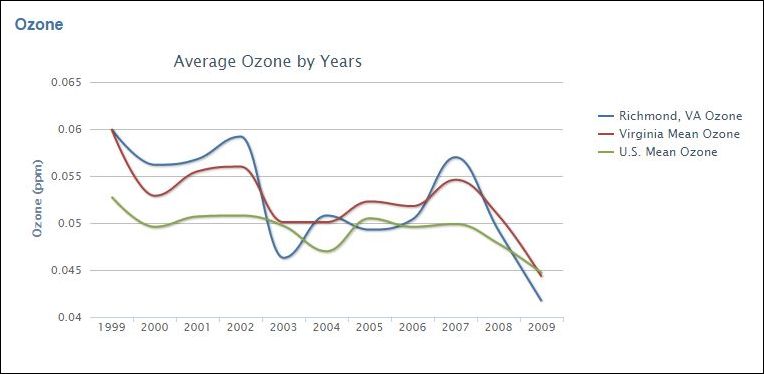

Although the city of Richmond does not have an ozone monitoring station, neighboring Henrico and Chesterfield counties do. And what do those stations reveal? Despite higher temperatures, ozone levels got better, not worse, over the decade of 1999 to 2009. The chart below, based on EPA data, show how the region’s average ozone levels declined markedly over that decade — dipping below the Virginia mean and the national mean.

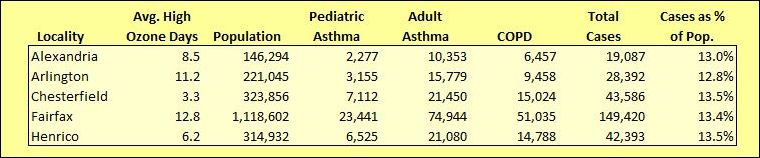

A quick Internet search did not reveal comparable data for more recent years. But an American Lung Association ranking listed the average high-ozone days between 2010 and 2012 for several localities with monitoring stations. Chesterfield County had weighted average of 3.3 and Henrico of 6.2. Ozone in Northern Virginia was much worse: Alexandria had a weighted average of 8.5 high-ozone days, Arlington 11.2, and Fairfax 12.8. Yet the incidence of asthma and COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) cases as a percentage of the population was virtually identical.

Obviously, there are many factors other than ozone associated with asthma. What might those be? WebMD lists these risk factors:

- Endotoxins in house dust.

- Animal proteins (particularly cat and dog allergens), dust mites, cockroaches, fungi, and mold. Changes that have made houses more “energy-efficient” over the years are thought to increase exposure.

- Indoor air pollution such as cigarette smoke, mold, and noxious fumes from household cleaners and paints.

- Environmental factors such as pollution, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxide, ozone, cold temperatures, and high humidity.

Whoah? What was that? Cold temperatures?

Yes, ozone is on the list. But it’s only one factor among many.

According to the Asthma and Allergy Foundation, race is a major risk factor, too. In recent years, the greatest rise in asthma was among African American children: One in six African-American children have asthma. For African Americans, the rate of emergency department visits is 330% higher and the rate of hospitalizations is 220% higher compared to whites. “Ethnic differences in asthma prevalence, morbidity and mortality are highly correlated with poverty, urban air quality, indoor allergens, and lack of patient education and inadequate medical care.”

Bacon’s bottom line: If we want to attack the high incidence of asthma in the Richmond region, we’re probably better off focusing on the socio-economic conditions of African-Americans than worrying about the impact of climate change on ozone and ragweed. Those are only two factors among many affecting asthma, and arguably far from the most important. In any case, thanks to coal-plant emissions controls and cleaner automobile engines, ozone levels probably will continue to decrease.