by James A. Bacon

To nobody’s surprise, we are getting confirmation that lower-income students are suffering the most from the way colleges and universities are responding to the COVID-19 challenge. Higher-ed enrollment has dropped significantly this fall, and the drop-outs are skewing toward the lower end of the income spectrum.

Some 100,000 fewer high school seniors completed financial aid applications to attend college this year, according to a National College Attainment Network analysis. Also, tuition deposits at 100 four-year colleges tracked by education research firm EAB are down 8.4% among families making less than $60,000 per year.

Those numbers are quoted by a Washington Post article highlighting the enrollment trend. Notice, though, how the Post spins the story (my emphasis):

The lower enrollment figures are the latest sign of how the economic devastation unleashed by the coronavirus crisis has weighed more heavily on lower-income Americans and minorities, who have suffered higher levels of unemployment and a higher incidence of covid-19.

The economic devastating was unleashed by the “coronavirus crisis” — not shutdown policies implemented by state governors and higher-education institutions but by the coronavirus crisis, as if the crisis itself were some tangible entity imbued with the will and power to make life-altering decisions. Thus, the Washington Post gets to hammer away on one of its favorite themes, economic disparity, without attributing any responsibility to the destructive policies — perhaps necessary, but destructive nonetheless — of governors and college presidents.

Among reasons cited for not returning to school this fall, according to data in the WaPo article, the greatest is frustration or uncertainty about online classes or changing class formats. Fifty-five percent expressed that concern. Second was fear of getting the virus, at 45%. Another 42% said they were unable to pay for school after income loss. All other reasons cited were purely secondary. Dissatisfaction with online learning was the most important consideration.

Writes the Post:

Students who have dropped out of college this fall overwhelmingly told The Washington Post that it was because of virtual classes. They preferred the supportive environment of attending in-person classes and being able to speak with teachers, fellow students and support staff. They struggled to find a quiet place at home to study and many lacked reliable Internet.

Financial considerations also played a role. The Post provides the example of Dario Magana-Williams, a Washington, D.C., resident who was accepted by, and planned to attend, George Mason University. The family’s finances took a hit when his father’s hours working at a restaurant were cut back. Paying out-of-state tuition to take some classes online and some in-person at GMU no longer seemed reasonable. “My parents saw no point to paying for online classes,” Magana-Williams said. “They didn’t think it was worth the tuition and were more comfortable with me staying home. … This is the reality of things.”

In other words, people are reluctant to pay the full tuition and fees (and in some cases room and board) for the experience of taking online classes. Lower-income households are more price sensitive, and many decided quite justifiably not to pay top dollar for a sub-par academic experience.

Here in Virginia, I get the sense that public universities made a legitimate effort to create COVID-free campuses. They required students to take COVID tests before entering campus. They required students, staff and faculty to wear masks. They mandated social distancing in dining halls. They set up testing and contact-tracing protocols. But they paid a price from decisions made in the spring to close campuses and finish classes online, which the perception of risk in every college student’s mind that the same thing might happen again… as in fact it has.

Here’s the hard cold fact: Driven by media-driven panic and hysteria, college administrators and board of trustees, not some amorphous “covid crisis,” made the decisions to close campuses and go online.

Here, according to the Virginia data from the Virginia Department of Health website, is the number of COVID-19 cases broken down by age bracket:

We can see that college-age kids — 18 to 22 years — are more likely than any other population segment to contract the virus. The high number of confirmed cases is the data point that sent college administrators into a state of panic and prompted all the extraordinary measures and, ultimately, the shift to online classes.

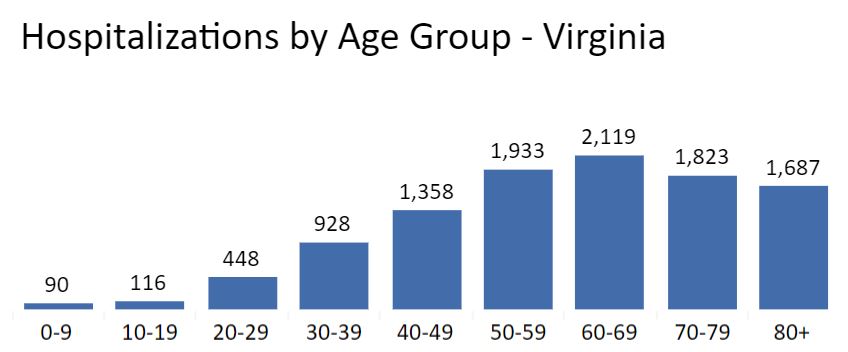

But we all know that college-age kids are highly resistant to the virus. Sure, the media has cherry picked some isolated tales of horror in order to make the case that “anyone” can catch the virus and suffer an excruciating fate, but the number of such cases are in fact uncommon. Here are the numbers for hospitalizations in Virginia:

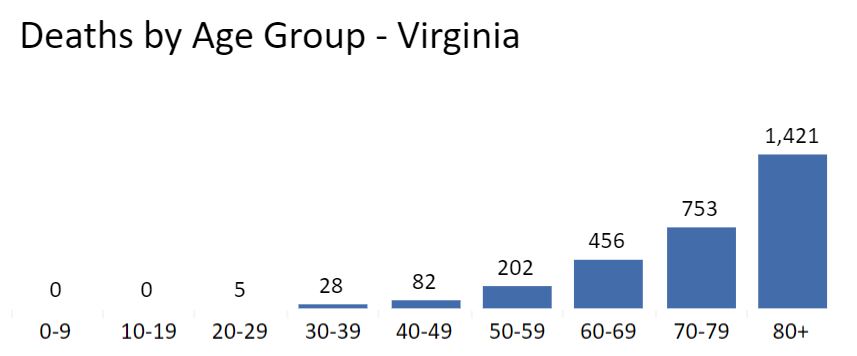

Very different story. Some 564 Virginians in the age range of 10 to 29 have been hospitalized. The number in the 18-to-22 age range of most college students would be a fraction of that, and the number of college-age students actually in college would be an even smaller fraction. But let’s not get exercised by that number, whatever it happens to be. Let’s look at the mortality data:

Five — that a 5 with no zeros after it — in the 10-to-29-year-old range in Virginia have died with COVID-19. We can reasonably suggest that fewer than five fell within the 18-to-22-year-old range, and, further, that some of those were not even attending colleges. Statistically speaking, the odds are that only one or two Virginia college kids have died from COVID-19.

That’s fewer than the number of drunken students who die from jumping out of fraternity house windows on a given year.

One can argue that a raging epidemic among college students on campus could spread to older, more vulnerable faculty and staff. It is entirely reasonable for college administrations to take extra precautions to protect them. Reasonable people can debate what measures would be appropriate. There are no easy choices. Every decision emtails tradeoffs.

But let us be clear, the metamorphosis of four-year residential college educations into an online experience was the result of conscious and calculated decisions made by administrators — probably in a herd response, as every institution calibrated its actions with an eye to what their peers were doing — in response to the epidemic. If lower-income students are choosing not to pay top dollar for a less-than-advertised educational experience, the blame rests with the colleges themselves, not the “covid crisis.”

Update: I feel like I jinxed things. A couple of hours after I wrote published this post, the Virginia Department of Health announced that the first 10-to-19-year-old in Virginia testing positive for COVID has died.