by Carol J. Bova

Upon the merger of Mountain States Health Alliance and Wellmont Health System in 2018, the first order of business for the newly created Ballad Health was shoring up its finances. If Ballad wasn’t successful at this, it would not have the resources to invest in the new services, facilities, programs, and equipment to improve community health it had promised as a condition of the merger.

Not all of Ballad’s actions were well-received. Some changes triggered community protests and county objections in its Tennessee and Virginia service territories. But the company did achieve its aim of bolstering cash flow. Here’s how Ballad went about it.

Job cuts. Financial conditions were adverse from the beginning. In an April 16, 2018 letter to the Tennessee Commissioner of Health, ten weeks into the merger, Ballad wrote that “due to the increased cost of labor, pharmaceuticals and supplies, and the continued shift to the outpatient setting from inpatient, operating income of the combined systems has declined by 123% since the same time in the prior year.”

The letter reminded the Commissioner that upon approval of the Terms of Certification, Ballad had announced it expected to eliminate about 250 administrative and support jobs. The company reduced the goal to 199, including 49 through attrition. Ballad advised the Commissioner “realignment” of 150 job would take place the next day.

Bond refinancing. The merger required some debt to be refinanced in the name of the new organization. Ballad’s Fiscal Year 2018 Annual report said the company had “refinanced $540 million of debt through issuance of a new series of bonds” through the Health and Educational Facilities Board of the Town of Greeneville, Tennessee. Series 2018A bonds saved $20 million per year in debt service.

The Town of Greeneville also issued Ballad Health Hospital Revenue Bond Series 2018B, Series 2018C, and Series 2018D. Financial advisor Bass, Berry and Sims said on its website, “We served as bond counsel to Ballad Health for a $950 million bond issue to finance new health care facilities and refinance some existing debt. Approximately $820 million of the bond issue is tax-exempt, and the refinancing portion resulted in about $40 million in net present value savings.”

Value-based contracts. Value-based contracts with government and commercial payors provided another source of income. Rather than being based on the volume of services provided, payments are tied to “achieving certain levels of quality and service, as well as managing total cost of care.” Hundreds of physicians and other providers from Virginia and Tennessee partnered with Ballad Health in an accountable care organization (ACO). Partners in ACOs share in savings and losses. AnewCare Collaborative, was started in 2012, one of only 18 ACOs to generate savings every year since they began. In 2018, AnewCare generated $7.2 million in savings and in 2019, $5.4 million. AnewCare received $3.3 million of the savings in Performance Year 2018 and $2.1 million in 2019.

Consolidation of overhead. Next, Ballad turned to streamlining its operations. Eliminating duplicate corporate positions reduced costs by $3.8 million. Where possible, Ballad also consolidated services between nearby hospitals. In Wise County, Va., for example, three full-service hospitals had a very low average daily inpatient census. Mountain View Regional in Norton is 2.4 miles from Norton Community Hospital and 11.8 miles from Lonesome Pine Hospital.

Ballad reported on the efficiencies in its Annual Reports.

- In FY 18, Ballad transferred the Mountain View Emergency Department to Norton Community Hospital, reducing costs by $400,000.

- Because the number of surgeries at Mountain View “was too low to meet industry-accepted patient safety standards,” surgery there was discontinued. Inpatient medical/surgical and intensive care services were moved to Lonesome Pine Hospital in August, 2019.

- One fixed CT scanner was decommissioned and mobile MRI services were discontinued.

- Laboratory, radiology, and pharmacy services were transferred from Mountain View to contracted services provided by Norton Community Hospital.

- In March, 2020, the Commissioner of Health approved Ballad’s Certificate of Public Need (COPN) to relocate inpatient rehabilitation services from Norton Community Hospital to Mountain View.

Not all transitions went smoothly. Community outrage greeted Ballad’s announcement that it would reduce the Holston Valley Level III Newborn Intensive Care Unit (NICU) to a Level I nursery for well babies and some born to mothers with addictions. Consolidating the NICU and pediatric services from Holston Valley Hospital in Kingsport, Tennessee to the one at Johnson City Medical Center, 24 miles away, reduced operating costs by $3.9 million and was expected to save $1 million per year.

To lessen the chances of having to transport newborns up to an extra half hour to the Johnson City NICU, Southwest Virginia mothers with a fetus in distress are transferred to the hospital prior to giving birth. The Virginia merger monitor said only two infants had to be transferred to Johnson City in 2019. There were no statements about the number of mothers in labor who had to be transported to Tennessee, or the amount of additional expense for the mothers.

In addition to the general community opposition to the downgrade of the Holston Valley NICU, the Sullivan County Attorney wrote a 75-page memorandum to the Tennessee Attorney General opposing the NICU closure and the downgrade of the Trauma Center at Holston Valley Level One (the highest for trauma care) to Level Three and Bristol Regional Medical Center from Level Two to Level Three. The Trauma Center consolidations were approved in the original agreement and restated on July 31, 2019.

Outpatient center moved to in-hospital. The Tennessee Merger Monitor’s report in March, 2020, explained why Ballad Health’s closure of a physician-based infusion center and its move to a hospital-based site was a public benefit, saving Ballad Health millions annually, even though it substantially increased the cost to patients and insurance companies.

Ballad Health made the move to reduce the cost of infusion drugs. A hospital-based site can buy outpatient drugs through the 340B Drug Pricing Program, a U.S. federal government program that requires drug manufacturers to provide outpatient drugs to eligible health care organizations at significantly reduced prices. The drug cost savings to Ballad Health by providing the cancer infusion drugs in a hospital facility is in the millions annually. When Ballad Health reduces costs, the cost of healthcare in the service area is reduced, which creates a public advantage. However the charges to patients and their payors (i.e., insurance companies) in the hospital-based infusion center are substantially higher than the charges for the same services provided in a physician-based site. The increase to patient and payor charges from this move has been the subject of several citizen complaints. Virtually no citizen pays charges, so the increase to charges does not significantly affect the amount a patient actually pays for cancer infusion therapy. The optics of the increase in charges was poorly received by the community, but the financial savings to Ballad Health, and therefore the community, justifies the move.

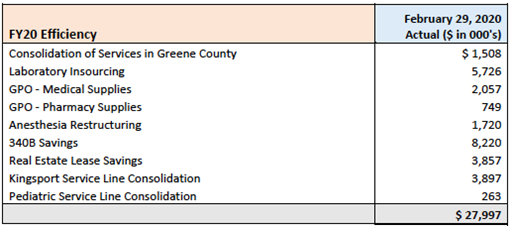

The tables below show Ballad’s descriptions of the efficiencies achieved for amounts greater than $200,000. Details of these efforts in annual report attachments were marked confidential and not available to the public.

“The incremental cash flow impact of this reduction of revenue is likely in the

range of $30 – $50 million annually,” stated the Ballad Health COPA FY20 Annual Report.

The changes improved Ballad’s bottom line. But the costs to insurance companies and some patients are higher. There are no reports yet on how insurance companies will react to the higher costs of in-hospital services instead of radiology and infusion centers in the communities. Patients have few, if any, options to go elsewhere. When the Local Advisory Council said citizens reported price increases, the COPA Monitor’s response was that the average increase in charges was in compliance with the Terms of Certification.

This article has concentrated on Ballad Health’s consolidations of services between nearby facilities, cost-cutting, and savings shared from the government and commercial payors from reductions in the cost of providing care. Whether that will ultimately reduce costs for patients is not known.

In Part III of this series, “Ballad Health Merger – Reshuffling, Reconstruction and Repurposing,” we will show how Ballad restructured the delivery of healthcare services.

Carol J. Bova is a writer living in Mathews County.