by James Wyatt Whitehead V

Tensions had reached a boiling point in the city of Baltimore on April 19, 1861. 160 years ago, a mob of pro-Southern sympathizers attacked the 6th Massachusetts Infantry as the unit was making its way by rail to Washington, D.C. There had been trouble the day before when regiments of Pennsylvania militia had passed through the city. Insults, bricks, and stones were hurled by several hundred “National Volunteers” of the pro-southern persuasion. Still the city police had managed to keep the situation under control. A decidedly Democratic and southern sympathizing city was ripe for violence in the wake of Fort Sumter and Abraham Lincoln’s call for volunteers to restore the Union.

When the 6th Massachusetts Infantry reached the Camden Station in Baltimore, it would be necessary to pull the rail cars by horse ten blocks down Pratt Street to the President Street Station. There was no direct rail connection due to different rail gauges of the period. Commanding Colonel Edward Jones issued instructions to his troops as the locomotive chugged into Camden Station:

The regiment will march through Baltimore in column of sections, arms at will. You will undoubtedly be insulted, abused, and, perhaps, assaulted, to which you must pay no attention whatever, but march with your faces to the front, and pay no attention to the mob, even if they throw stones, bricks, or other missiles; but if you are fired upon and any one of you is hit, your officers will order you to fire. Do not fire into any promiscuous crowds, but select, any man whom you may see aiming at you, and be sure you drop him.

Awaiting the 6th Massachusetts was a mob of southern sympathizers. The street was blocked. The horses could not move the cars to the next station. Four companies of men disembarked to clear the way. An all-out brawl ensued as bricks and stones flew and volleys of musket fire replied. The Baltimore Police were able to wedge themselves between the mob and soldiers allowing the men of the 6th to board the train at the President Street Station. Four soldiers were killed and 36 wounded in the event. Twelve civilians were also dispatched in the mayhem.

The passion of April 19th had far reaching consequences. Maryland Governor Thomas Holliday Hicks acceded to the call of a special convention to debate Maryland’s secession. Baltimore and Annapolis would be under military occupation for the remainder of the war. Lincoln moves quickly to suspend habeas corpus, which led to a Constitutional crisis in the Supreme Court case of Ex Parte Merryman.

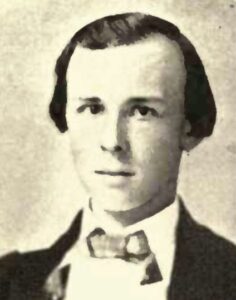

Meanwhile, deep in the heart of Louisiana, college professor and native Marylander, James Ryder Randall, was preparing lessons at Poydras College. He could not complete the task at hand, for he had just learned of the death of a friend, Francis Ward, a civilian casualty in the Baltimore Riot. In a spasm of creativity, Randall penned the poem, “Maryland, My Maryland.”

The nine-stanza poem is a call to arms to avenge the bloodshed on the streets of Baltimore. Lincoln is disparaged as a “tyrant” and “despot.” Randall’s poetry invokes the names of Maryland heroes from the Revolution and the Mexican War. “Maryland, My Maryland” is a plea to citizens to join with Virginia in secession and the motto of “sic semper” is a key centerpiece. The poem was transformed into song by Baltimore socialite Jennie Cary. She set the tune of “Maryland, My Maryland” to the old Christmas song “O Tannenbaum.” It was a common practice in this period to set new songs to the tune of songs that were well known to gain rapid acceptance and popularity.

One often thinks of “Dixie,” “The Bonnie Blue Flag,” and “When Johnny Comes March Home,, as southern songs of war. “Maryland, My Maryland,” became one of the most popular Civil War songs for southern soldiers. In terms of popularity, physician and poet Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. equated the Maryland state song with “John Brown’s Body.” “John Browns’ Body” was also set to a familiar revival song from the days of camp meetings, “Say Brothers, Will You Meet Us“.

When Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia crossed the Potomac River at White’s Ford in Loudoun County, he had the marching band strike up the tune of “Maryland, My Maryland.” As a long line of men waded the waters and into Maryland, a campaign of claiming the Old Line state was on Lee’s mind and final victory. The scene of Confederate soldiers parading into Unionist Frederick, Md., was accompanied by this new song of rebellion. The bloody struggle of the Battle of Sharpsburg dashed hopes for an end to war and of Maryland joining the Confederacy. When Lee’s army crossed the Potomac and into Maryland again in 1863, “Maryland, My Maryland” was not played on the long road to Gettysburg. James Randall would go down in the history books as the “poet of the Lost Cause.”

“Maryland, My Maryland” has been the official state song since 1939 and, since 1974, there has been an annual call to replace the state anthem due to the controversial lyrics. In recent years the state song has lost its luster, although it is played from time to time. As recently as 2017, the United States Naval Academy Glee Club performed the old tradition at the Preakness Stakes. In 2020, the Maryland legislature nearly adopted a removal, but a limited session due to COVID-19 shelved the idea. This year a bill has been reported out of the state assembly and is headed to the desk of Governor Larry Hogan. He has not indicated whether he will sign or veto the measure. The bill calls for the removal of “Maryland, My Maryland” with no replacement.

Fortunately for Virginia, we have already been down this road and during calmer times. In 1997, “Carry Me Back to Old Virginia” was retired from the state song to state song “emeritus.” Stay “tuned” for the next part that explores the rich history of our former state anthem.

James Wyatt Whitehead V is a retired Loudoun County history teacher.

A picture of James Ryder Randall. Poet of the “Lost Cause”.

James Ryder Randall 1861 – Maryland, My Maryland – Wikipedia

Currier and Ives Lithograph depicting the Baltimore Riot as the “Lexington of 1861”.

Currier & Ives – The Lexington of 1861 – Baltimore riot of 1861 – Wikipedia

Rare photograph of Stonewall Jackson’s men marching into Frederick, Md., singing the tune “Maryland, My Maryland.” It was not well received.

Confederates marching through Frederick, MD in 1862 – Maryland campaign – Wikipedia

Map of the route taken by the 6th Massachusetts during the Baltimore Riots.