Stakeholders in Virginia’s electric grid got a close-up look last week at the wild and woolly world of Clean Power Plan regulation. One of the few things that can be said for certain is that the plan will make a complex industry even more complicated. To make an informed decision about how to proceed, Virginia policy makers will have to acquaint themselves with, among other concepts, “ERCs,” “leakage” and “new source complements.”

Representatives of Virginia’s major electric utilities, independent power producers and environmental groups gathered in Richmond Friday at the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) to see if they could reach a consensus on whether Virginia should choose the “rate based” approach to reaching the plan’s aggressive CO2 reduction targets or the “mass based” approach. The proceedings were collegial, but nothing like a consensus emerged after several hours of discussion.

Adding to the complexity of choosing a regulatory path is the uncertainty of what legal fate will befall the Clean Power Plan. Just days ago the U.S. Supreme Court issued a stay, halting implementation of the plan, until federal courts had time to rule on its constitutionality. As of Friday, many people assumed that a 5 to 4 conservative majority would reject the plan on the grounds of constitutional overreach, allowing utilities and state regulators to continue business as usual. But the weekend death of conservative justice Antonin Scalia threw even that seeming certainty into question.

Before the Supreme Court issued its stay, Virginia’s DEQ had until June 2016 to submit a State Implementation Plan to the Environmental Protection Agency, although the deadline could be extended one to two years, depending upon circumstances. A critical decision would be whether to go with a rate-based plan, which sets CO2 emissions goals on the basis of the number of pounds of CO2 emitted per megawatt/hour, or a mass-based plan, which sets CO2 goals based on total pounds emitted.

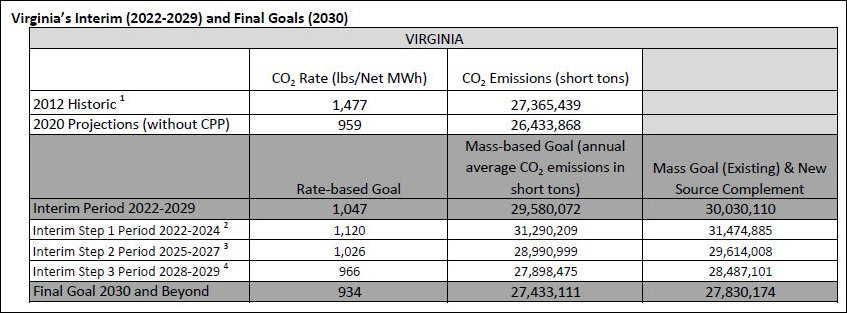

Under the rate-based plan, Virginia power plants would have to cut their CO2 emissions from 1,047 pounds to 934 pounds per megawatt/hour of electricity generated by 2030. Alternatively, under the mass-based plan, Virginia power plants would have to cut total CO2 emissions from 30.0 million short tons to 27.8 million by 2030.

In case the Clean Power Plan survives its legal challenge, DEQ is moving forward with its stakeholder consultations. At present, the regulated power companies — Dominion Virginia Power, Appalachian Power Co., and the Old Dominion Electrical Cooperative — are leaning toward the rate-based plan, although each company insists that its positions are preliminary, pending more thorough analysis. By contrast, some independent power producers such as Birchwood Power Partners, owner of a coal-fired cogeneration facility in King George County, and Covanta, owner of the Arlington-Alexandria Energy-from-Waste facility in Alexandria, favor the mass-based approach. Environmentalists favor the mass-based approach with a “new source complement” (explained below).

While round-table discussion Friday found no unanimity, it did surface several critical issues.

Ease of implementation. The most consistently cited reason to go with the mass-based plan is that the federal government has successfully implemented caps on other pollutants, such as sulfur dioxide emissions responsible for acid rain. In effect, there is a template to follow, which there is not with the rate-based approach.

Interstate trading. An advantage of the mass-based plan would be the ability to trade allowances with carbon emitters across state lines. By enlarging the pool of potential trading partners, in theory it should be possible to make more advantageous trades resulting in greater efficiency.

Allocation of allowances. Adoption of a mass-based plan would require DEQ to allocate CO2 pollution allowances — but on what basis? Will the allowances be auctioned off to those willing to pay the most for them? Will they be distributed equally among carbon emitters on the basis of CO2 released into the atmosphere? If so, is that fair to those who invested heavily in carbon reduction before the Clean Power Plan? Should there be set-asides for special cases? Can any of this be done in a way that is not dictated by ideology, special interest and politics?

Growth in electricity output. The most consistently cited reason to favor the rate-based approach (CO2 emissions per unit of electricity generated) is that it will accommodate growth in electricity demand and output. The question, then, is whether electricity demand will increase in Virginia between now and 2030. The utilities err toward the side of caution and assume that demand could increase as much as 1% per year; environmentalists respond that demand forecasts historically overstate actual demand, and that demand can be curtailed by energy efficiency and demand-side management plans.

Leakage and level playing fields. The mass-based approach comes in two flavors — one with a “new source complement” and one without. The Clean Power Plan would treat existing fossil fuel-burning power plants more stringently than new ones with the consequence that there could be “leakage,” in which operators shut down old plants and electricity production shift to new ones using the latest technology subject to different regulations. Adding a “new source complement” to the mass-based approach, which would include CO2 from new sources under the statewide cap, would help level the playing field and reduce leakage. A feared drawback of “new source complement” is that it would make it even harder to expand electricity-generating capacity.

ERC glut or shortage? Under a rate-based approach, regulators would assign each electricity generating unit (EGU) an allowable CO2 emission rate. If a generating unit manages to generate less CO2 than its target, it garners an Emission Rate Credit, or ERC, which it can use to offset the excess CO2 emitted by another generating unit. ERCs can be traded and sold. The idea is to steer capital to those units that can most cost-effectively reduce CO2 emissions. The problem is that the pros/cons of the rate-based approach is difficult to evaluate because no one knows how many ERCs will be generated or what the demand for them will be. A glut of ERCs would reduce their value; a shortage would increase their value. Making a supply/demand forecast all the most difficult is the fact that the interstate market for ERCs will depend on the number of other states adopting the rate-based approach, which itself is hard to predict.

Billions of dollars ride on the approach DEQ chooses. Under their worst-case scenarios, the big utilities would find many of their facilities uneconomical; shutting them down would create potentially billions of dollars in stranded costs that could be passed on to rate payers. Conversely, a worst-case scenario for some independent power producers would put them out of business enitrely. Both the utilities and independents are maneuvering to minimize their exposure, big industrial customers are seeking the least-cost approach, and environmentalists are pushing for the maximum CO2 reduction achievable.