by James A. Bacon

Hamilton Lombard has posted some fascinating data on the University of Virginia Demographic Research blog, Stat Chat, that illuminates the income gap between whites and blacks. For Lombard’s spin on the data he presents, I suggest that you read his commentary here. It’s different from my take. I wouldn’t say that his interpretation and mine are in conflict, but I don’t want to imply that he would necessarily agree what I’m writing here.

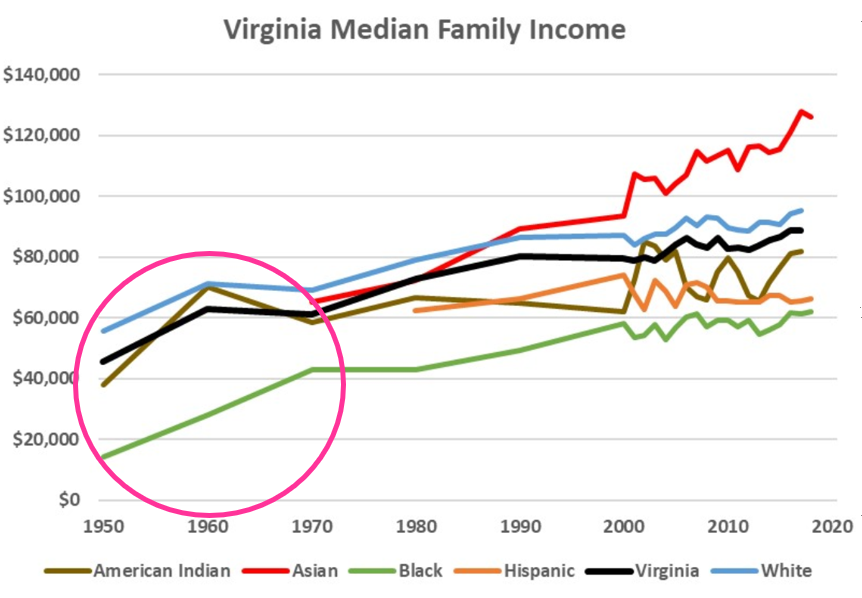

The black-white income gap. The first point worth noting is that between 1950 and 1970 (inside the magenta circle in the chart above), when blacks’ economic opportunities were curtailed by segregated institutions, the gap between black and white incomes narrowed significantly. In the 50 years since then, the income gap between blacks and non-blacks has not budged.

“The fact that the income gap for Black Virginians has not changed considerably since 1970 is particularly notable,” writes Lombard, “because the intention of the Civil Rights Era reforms and the Great Society programs that have existed since the late 1960s are in large part to help close the income gap.”

There is a world of difference between intentions and outcomes. The architects of the Great Society programs did not predict the outcome that Lombard alluded to. They expected their policies would reduce the gap. However, they did not anticipate the impact that their policies — along with other cultural trends — would have on the black family structure, black resilience and black agency. The dominant Narrative today is that blacks are helpless victims of systemic white racism and institutional racism and that political action (mediated by liberal whites) is the only way to improve their lot in life. I cannot imagine a narrative more calculated to sap black striving and initiative.

The Asian-everyone else gap. Take a look at the red line, representing median income for Asian families. As recently as 1985, Asian and white household incomes were roughly equal. Asian incomes have taken off since then. That is the big income-gap story of not only Virginia but the United States. The question we all should be asking is this: Why have Asians done so much better than everyone else over the past 35 years? Even white people should be asking how they can emulate Asians’ success.

The politically driven fixation by media, academia and political establishment on the black-white gap has totally obscured the Asian-everyone else gap. There’s a reason for that. Acknowledging the Asian-everyone else gap would undermine the narrative that inequity in American society derives from “white privilege.” Re-focusing the issue on the Asian-everyone else gap would highlight the idiocy of the Oppression Narrative because (a) Asians are supposedly “persons of color,” (b) they have far less political clout than blacks and Hispanics, and (c) no one advances a serious claim that they enjoy institutional privilege of any kind.

But if Asians don’t enjoy institutional privilege, to what do we attribute their ability to generate higher incomes than whites and other racial/ethnic groups in Virginia? Could it be social and cultural factors, such as the strength of Asian families, future orientation, emphasis on academic achievement, lower proclivity for criminal behavior, and a willingness to defer gratification? A focus on the factors driving Asian achievement would obliterate the construct of the Oppression Narrative, hence must be ignored at all costs.

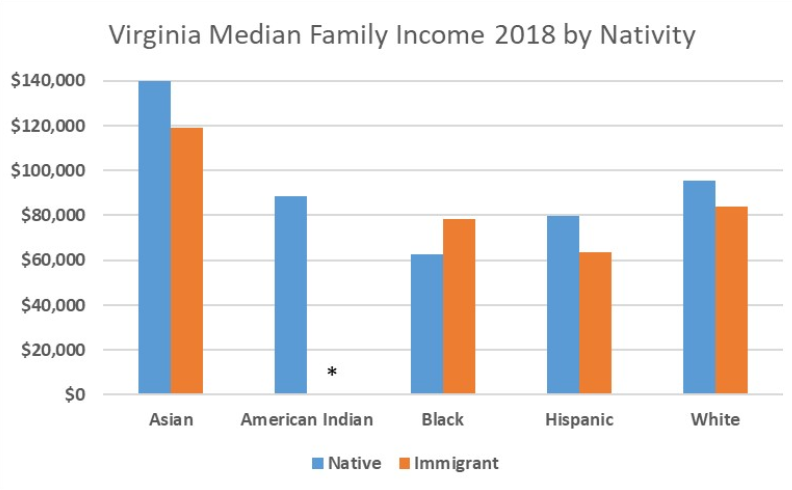

The black immigrant/native gap. In the chart above, Lombard compares the differences in family income between natives and immigrants for the four major racial/ethnic groups. Asian immigrants make less money on average than native-born Americans of Asian ancestry. The same applies to white immigrants and Hispanic immigrants, but not black immigrants. Lombard attributes the income gap between natives and immigrants for whites, Asians and Hispanics to the fact that natives generally enjoy higher levels of education than immigrants. For blacks, the situation is the reverse. Black immigrants in Virginia tend to have higher levels of educational attainment than native-born blacks.

Proponents of the Oppression Narrative can fall back upon the argument that black immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean never suffered the horrors of slavery and racial segregation that shaped the native African-American experience. Such an argument fails to take into account the inequities resulting from colonialism in African and the combination of slavery and colonialism in the Caribbean. More importantly, the black immigrant-native gap gut-punches the argument that skin color is an important determinant of an individual’s income in the U.S.

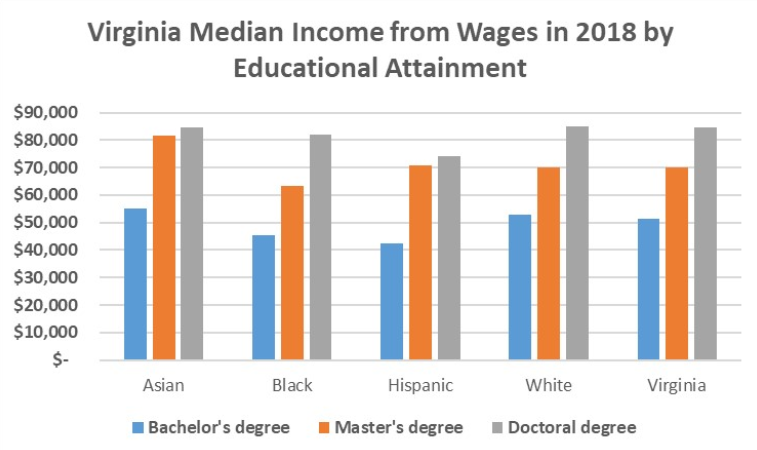

The real gap: educational attainment. The income gap is largely an education achievement gap. When comparing median household incomes of Virginians holding a B.A. degree, blacks earn 90% of what other Virginians do. The income gap for blacks with masters or doctoral degrees, as seen in the chart above, almost disappears. Lombard has an explanation for the differences that do exist:

While there is no single reason why Black Virginians with a bachelor’s degree still earn less than other Virginians with a bachelor’s degree, one reason may be that less preparation for college causes Black college students to be underrepresented in the more competitive college majors that typically lead to higher paying jobs. In context, Asian Americans are over-represented in higher paying fields, particularly STEM, which in turn causes them to earn more on average than other Americans with the same educational attainment.

Bacon’s bottom line: The racial income gap does not reflect broad, systemic racism, it reflects the educational achievement gap. To create a society in which blacks enjoy equal opportunity, we need to address the failures of our educational system. According to the Oppression Narrative, Virginia’s educational system is infected with structural racism. I have endeavored to refute that proposition on many occasions. Whether one agrees with my analysis or not, that’s the dialogue we need to be having.