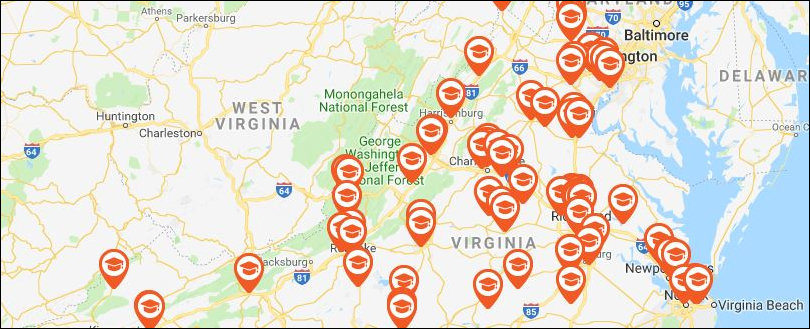

Location of schools belonging to the Virginia Association of Independent Specialized Education Facilities. See member list here.

There are more than 90,000 kids classified with disabilities in Virginia’s public school system. They typically require more resources than other students — smaller class sizes, educational assistants, and the like — and local school districts are struggling to pay for them. Not all of the funds spent by the Commonwealth of Virginia on behalf of kids with disabilities goes to public schools, however. Millions of dollars support the roughly 80 private day schools that specialize in educating children with specific disabilities from autism to dyslexia.

Not surprisingly, when state resources are finite, not everyone agrees on who should get what. Some say that many children with disabilities could be schooled effectively but at less expense in public school settings than in highly resource-intensive private schools. Private school advocates counter that their higher staff ratios and specialized training, though more expensive, provide better outcomes. But nobody knows for sure because the private schools don’t collect data in a way that would inform the debate.

A work group organized by the Office of Children’s Services produced a document last month identifying ten outcomes that the private schools should track. With minor exceptions, the list of outcomes reflects a consensus view of the public-school, private-school, and government stakeholders. The outcomes include:

- Graduation rates (same as public schools).

- Attendance (same as public schools).

- Individual student progress in four domains: communication skills and social functioning, acquisition of knowledge and skills, adaptive behavior, and daily living skills and self-reliance.

- Standardized test scores (same as public schools).

- Return to public school setting.

- Post-secondary transition (subsequent enrollment in training program, enrollment in college or employment).

- Suspension and expulsion: percentage of students suspended or expelled greater than 10 days in a school year.

- Restraint and seclusion: number of incidents in which students are put under physical restraints or are held in isolation.

- Parent satisfaction based on parental surveys.

- Student perspectives based on student surveys.

Students with disabilities, the vast majority of which are cognitive or emotional, are not easily categorized. They fit on a spectrum ranging from severely disabled (unable to keep up with class work, frequently disrupting class, often violent) to mildly disabled (able to mainstream with non-disabled students). Virginia’s schools have evolved a comparable spectrum of response.

Under federal law, disabled children are supposed to be placed in the “least restrictive environment.” If they can’t be mainstreamed in classes with non-disabled students, they might be taught in a self-contained classroom with other disabled students for some or all of their classes. Some school systems even have separate schools for a small number of students. If multiple attempts at intervention within the public school system fail, a student’s IEP team (which develops an Individualized Education Plan) can refer him or her to a private school with greater resources per student.

For example, the John G. Wood School at the Virginia Home for Boys and Girls in the Richmond area, which focuses on kids who have been physically, sexually or emotionally abused, has a 25-person staff to educate 45 students. Students are often two, three, even four years behind grade level. Not only do they require academic remediation, they need work on self-defeating behaviors that interfere with academic learning. State funding covers only half the expense. The Virginia home makes up the difference with philanthropic dollars.

The private schools get the hard cases. Most of their students have failed their SOLs, and they don’t have any immediate prospect of being able to pass them. These severely disabled children, say private-school advocates, need a different yardstick for measuring progress, which is reflected in the “individual student progress” metrics.

There are no easy answers here. School districts are struggling with tight budgets that have not kept pace with inflation since the last recession. Federally mandated spending on children with disabilities is crowding out spending on other priorities. While the number of students classified as disabled has not increased dramatically over the past decade, there is evidence that the severity of the disabilities is getting worse. Meanwhile, parents are all over the place. Some demand their children be mainstreamed, potentially imposing their disruptive behavior on classmates, while others demand that their children be placed in environments with access to the greatest resources.

There is one possible win-win solution: Identifying the programs that produce the best outcomes. There are many different approaches to helping disabled kids. Other than the conviction that “early intervention” is a good idea, people don’t seem to agree on much else. Also, some schools (both public and private) are run better than others.

In a world of finite resources, public dollars should be steered to those programs and settings produce the best outcomes. And the first step is agreeing on the outcomes to be measured. In at least this one respect, Virginia seems to be moving in the right direction.