by James A. Bacon

What are the secrets of successful metropolitan regions? According to conventional economic-development thinking here in Virginia, success hinges upon the ability to maintain a positive business climate, a concept that encompasses everything from tax rates to the tort system, the transportation network to the education level of the workforce. But a new publication by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), “The Metropolitan Century,” identifies a critical variable rarely discussed in Virginia: the fragmentation of municipal governance.

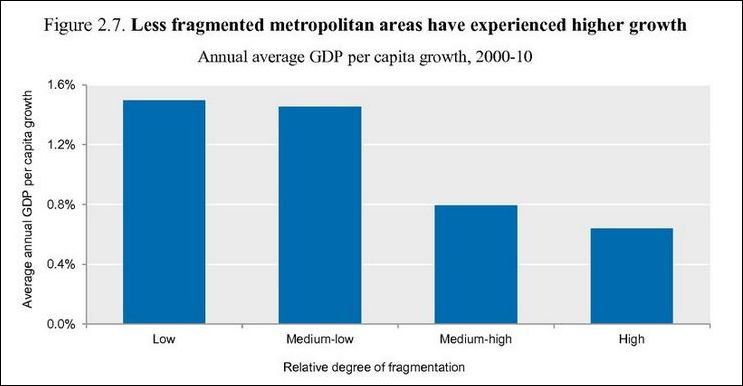

Metropolitan regions characterized by higher levels of municipal fragmentation tend to experience lower economic growth rates than metros with less fragmentation, contends the OECD report, as seen in the chart above. Metropolitan regions run the gamut in the degree of fragmentation, from the United Kingdom with an average of 0.4 municipalities per 100,000 residents to the Czech Republic with an average of 2.43 per 100,000. All other things being equal, the report says, “For each doubling in the number of municipalities per 100,000 inhabitants within a metropolitan area, labour productivity in the metropolitan area decreases by 5-6%.”

(I would surmise that the number of municipalities in Virginia falls in the “moderately low” category. For example, the 1.7 million inhabitants of the Hampton Roads metropolitan area are governed by 16 jurisdictions, including two in North Carolina, or slightly less than 1.0 per 100,000 population.)

Fragmented government inhibits economic growth through its impact on transportation and land use, suggests the OECD report. The inability to plan regionally can result in “sub-optimal provision of transportation infrastructure” that falls short of its potential to provide the connectivity required by a productive, growing regional economy.

In the context of large urban agglomerations, land use planning and transport planning are often the fields where the need for co-ordination is greatest. … Housing and commercial developments need to be well connected to other parts of the urban agglomeration, and public transport in turn relies on a minimum population density to operate efficiently.

Integrating transport and land-use planning makes it easier to utilize value-capture tools for financing transportation infrastructure. “Public spending for infrastructure increases the price of adjacent land,” states the report. “Often, this price increase provides a publicly funded windfall profit to land owners or developers. Land-value capture tools aim at recapturing these windfalls from developers in order to (partially) fund the infrastructure investment.”

Echoing arguments that EM Risse made on this blog years ago, the OECD report observes that administrative borders in metropolitan areas have not evolved in concert with economic and social patterns.

While good governance structures are no guarantee for good policies, it is very difficult to design and implement good policies without them. … Administrative borders in metropolitan areas rarely correspond to these functional relations. Often, they are based on historical settlement patterns that no longer reflect human activities.

A few decades ago, there was a move in Virginia to consolidate cities and counties in order to achieve administrative efficiencies and economies of scale. There were some notable successes — Virginia Beach merged with Princess Anne County, Suffolk merged with Nansemond County — but the movement petered out. The OECD report spelled out reasons for resistance to consolidation that apparently apply across the economically developed world:

Common reasons for the persistence of administrative borders are strong local identities and high costs of reforms, but also vested interests of politicians and residents. Even if policy makers try to reorganize local governments according to functional relations within urban agglomerations, it is often difficult to identify unambiguous boundaries between functionally integrated areas.

There doesn’t seem to be any appetite for consolidating local governments in Virginia, but the OECD report does suggest an alternate strategy: Identifying specific functions that can be transferred to regional authorities.

Would it be worth the effort to invest political capital in such endeavors? Take a look at the chart at the top of this post. The big dividing line in economic growth is between medium-low and medium-high fragmentation. Assuming Virginia metropolitan regions fall into the medium-low category — and I do confess that I do not know exactly what the dividing line is — there doesn’t seem to be much of a growth premium from consolidating our way into “low fragmentation” status. Indeed, I would argue that some competition between jurisdictions in a metropolitan area is a good thing — the ability of inhabitants to “vote with their feet” helps keep the politicians honest.

But that’s a shoot-from-the-hip reaction based upon one OECD chart. If Virginia is serious about positioning itself for economic prosperity in the years ahead, our governance structures, rooted in 19th-century settlement patterns, surely need to keep up with economic reality.