By James C. Sherlock

I used to write and later in my career approve daily air plans for aircraft carriers.

There were a lot of individual rules and dependent variables.

Adding or subtracting the number or sorties, or ordnance, or changing cycle times, or a lot of other things after the plan was written required a restructuring of the entire plan, not just part of it.

Back then we had ten squadrons with nine types of aircraft onboard, each configurable.

The aircraft handler had to make the right aircraft available on the flight deck, crews needed to be ready, the ship’s captain had to plan his course to keep the ship in position to turn into the wind for longer or shorter times, air refueling needed to be re-calculated, training ranges needed to be re-scheduled, the right ordnance had to be built up, divert fields had to be notified.

You get the idea.

The Virginia House and Senate are about to negotiate with one another and with the Governor and his Secretary of Health and Human Resources, John Littel, over how much and how additional state money will be spent in FY 2024 (starts July 1, 2023) for behavioral health.

Nice problem to have, you think.

And it may prove to be, but it is crucial that the budget language not overly restrict where the money is spent. The current plan will need to be changed and integrated for more or less money and program-specific uses than planned.

As with my earlier example, there are a lot of rules and dependent variables. Virginians want the money spent efficiently and effectively.

Those two objectives are harder than they may sound.

The current plan for spending an additional $230 million in the fiscal year starting in July on behavioral health has been balanced for a three-year rollout, and needs to remain executable with whatever additional funding is appropriated.

I am here discussing the matter of budget language that may attempt to restructure the executive plan, not just the amounts.

Changes to the individual components of the plan depend on resources that may not respond well to additional, or less, money than requested.

There is specifically the obstacle of a major shortage of qualified providers in most areas of the state. But the mix of program, construction and personnel funds must also remain balanced.

Given all the moving parts and choke points of the components of the plan, I recommend giving the executive branch more space to work with additional funds than either version of the current budget may allow.

We saw how fund restrictions worked, or didn’t, with COVID funds for schools.

The numbers: Both Medicare and Medicaid fund behavioral health services, as do private insurers, depending upon the specifics of the plans.

In Virginia, the Governor asked this year for a $230 million dollar increase in the state FY 2024 behavioral health funds provided in last year’s biennial budget. That would bring total state spending on behavioral health care to over $660 million in the next fiscal year.

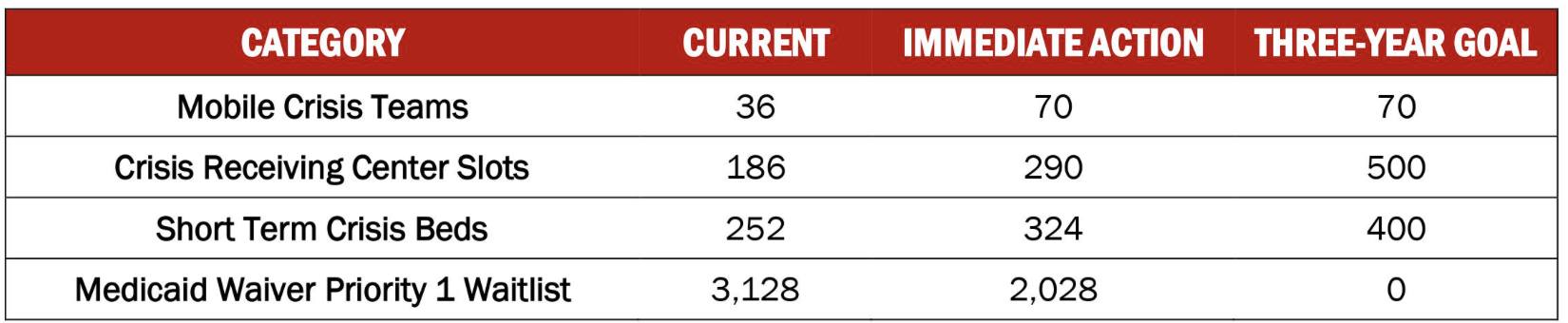

The additional money is to pay for the transformation shown in the chart above.

The House is proposing a $182.5 million increase, $47.5 million less than the Governor requested, and the Senate $370 million, $140 million more than the request.

No shortage of additional ideas not funded. Behavioral health needs of Virginians are served by:

- public sector providers including:

- eleven state facilities;

- some of Virginia’s federally qualified health centers (federally funded nonprofit health centers or clinics that serve medically underserved areas and populations regardless of ability to pay) and free clinics;

- Virginia’s Community Service Boards; and

- Local government and community organizations.

- private facilities and providers paid by government and private insurance.

I offered yesterday some ideas to transform state behavioral health facilities and to improve clinical services at the top of that sector, research hospitals. Neither is funded in the budget.

Others have written compellingly of the need to better pay private providers through Medicaid and Medicare.

Medicaid funding is not on the table in the mental health budget under discussion.

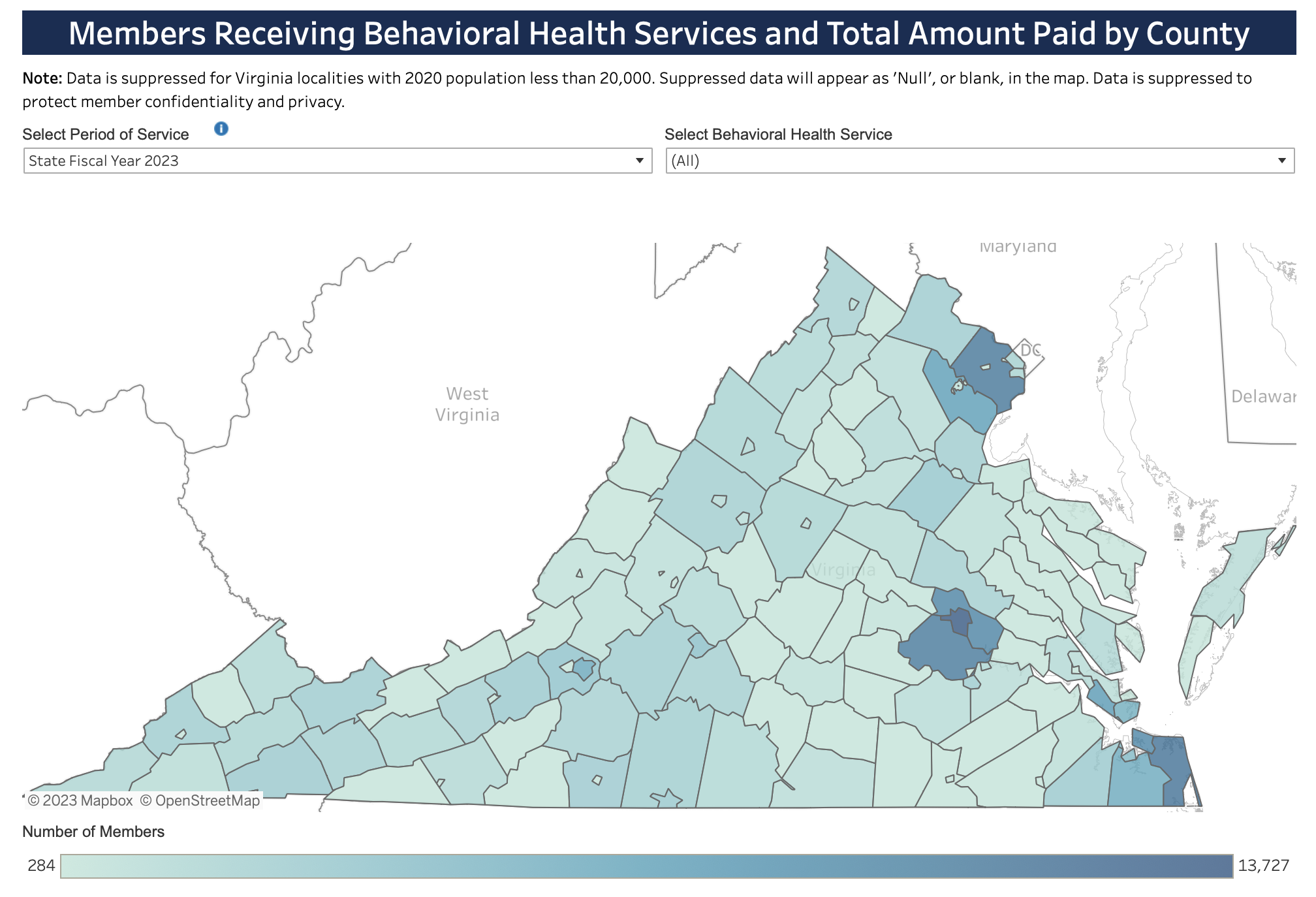

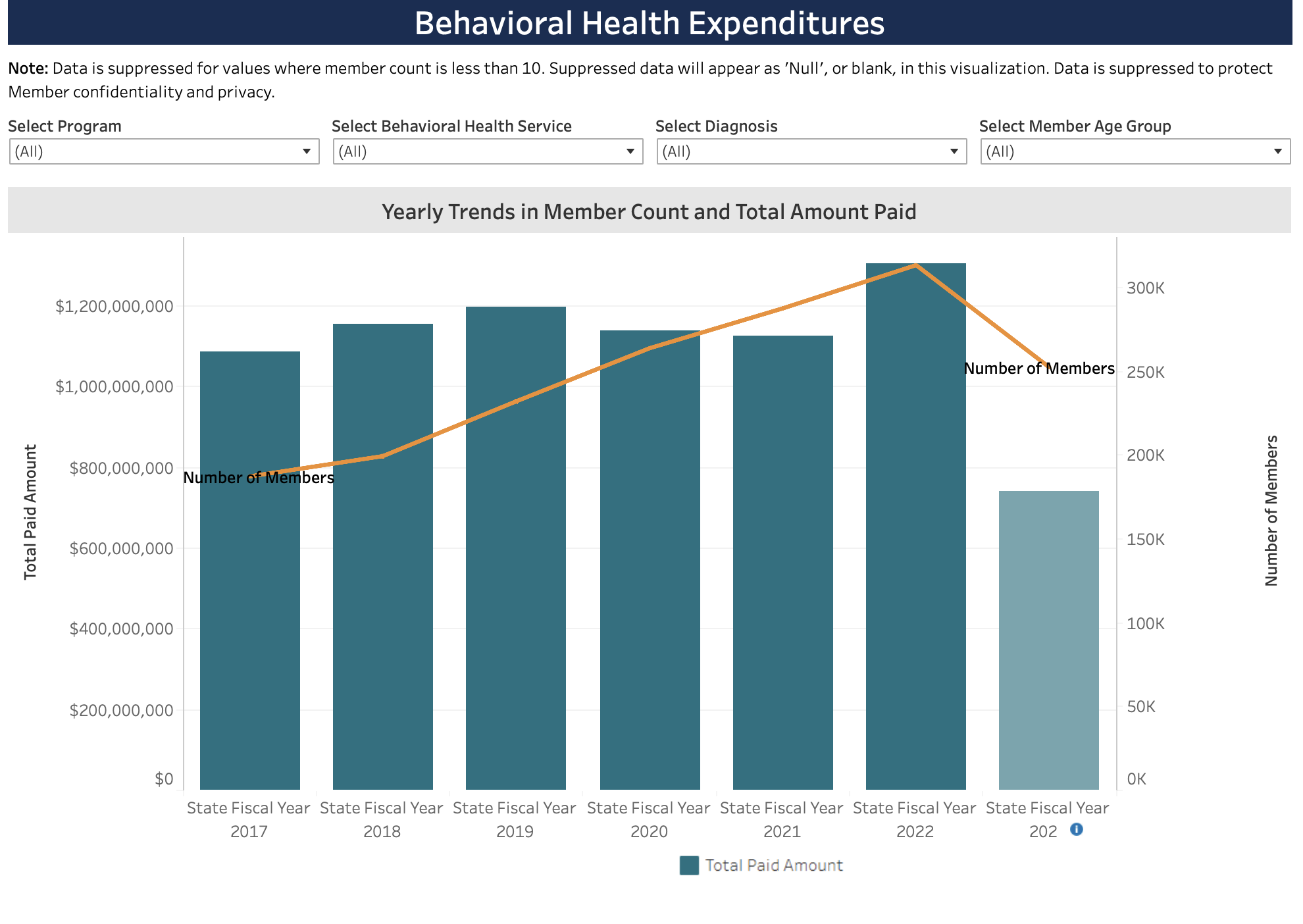

The Virginia Medicaid behavioral health services dashboard is here.

Medicaid is already in flux as the member count is reduced by the withdrawal of federal COVID rules that temporarily prevented reduction of the rolls for people whose income exceeds Medicaid limits.

Medicaid is already in flux as the member count is reduced by the withdrawal of federal COVID rules that temporarily prevented reduction of the rolls for people whose income exceeds Medicaid limits.

A specific plea in that article was for an increase in payment rates for two Medicaid services delivered to children and families, Therapeutic Day Treatment (TDT) and Intensive In-Home (IIH).

A specific plea in that article was for an increase in payment rates for two Medicaid services delivered to children and families, Therapeutic Day Treatment (TDT) and Intensive In-Home (IIH).

Senate and House. The Senate and House of course have very specific ideas of where new behavioral health money should be spent.

The Senate version, for example, moves some of the chess pieces around the board in addition to providing more money than the Governor requested.

The House version does the same with less additional money than requested.

Shortages of providers. I have no reason to think any of those are not good ideas, but many of them will be impacted by the shortages and maldistribution of qualified providers.

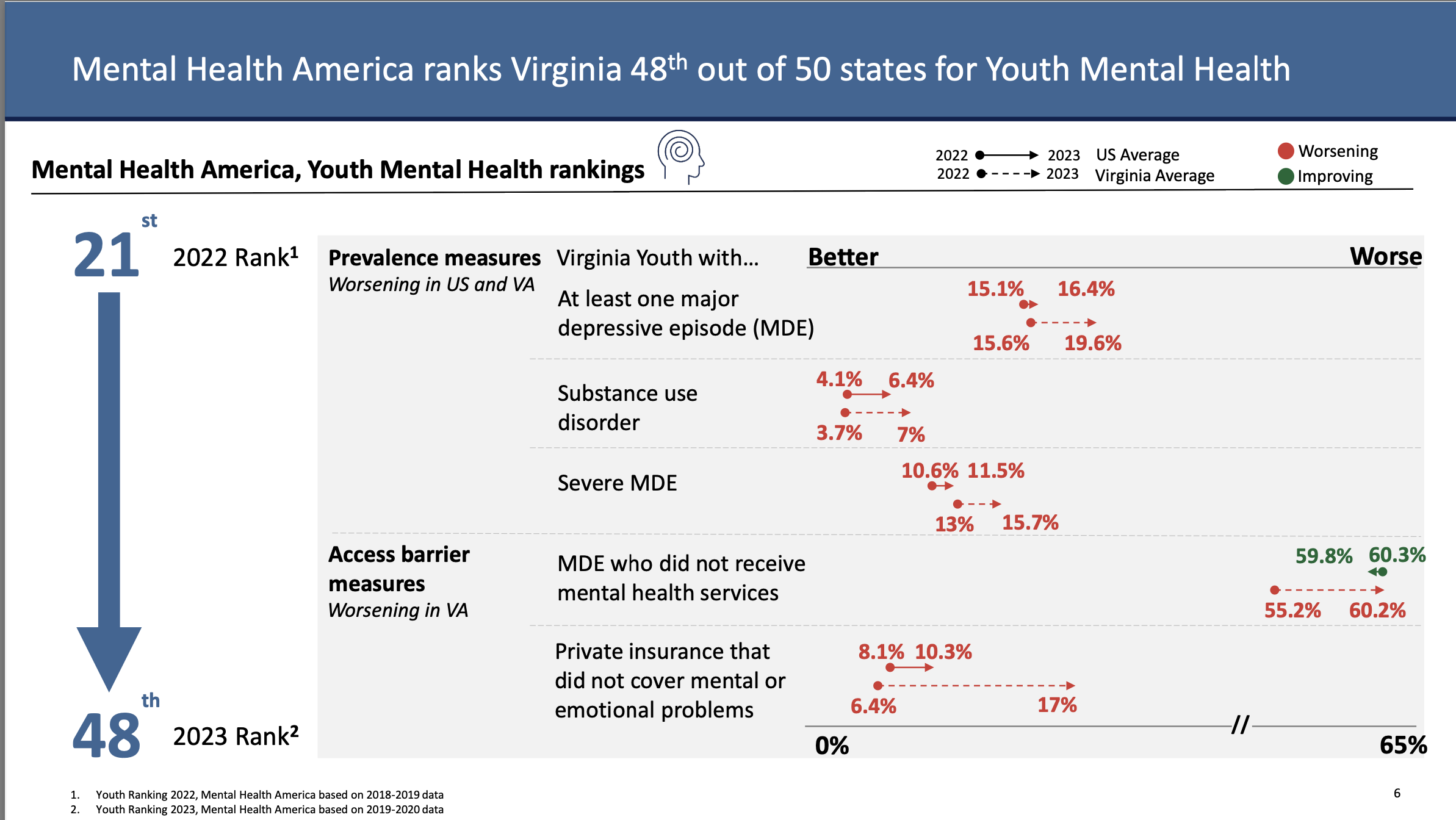

See below the Health Resources Service Administration visualization of shortages of mental health professionals in Virginia and the Mental Health America ranking of Virginia for youth mental health.

Bottom line. There are a lot of targets for additional money, some in the budget and executive department plan and some not. And there are a lot of obstacles to overcome to achieve positive results.

The latest bug in budget negotiations is reconsideration of the accuracy of previous revenue projections given the increased potential for a recession because of troubles in the banking system.

It’s always something.

Whatever the final additional appropriation may be, I recommend, because of the interdependence of and obstacles to various pieces of the plan, the General Assembly give the administration more flexibility than is often allowed in how to spend the money appropriated.