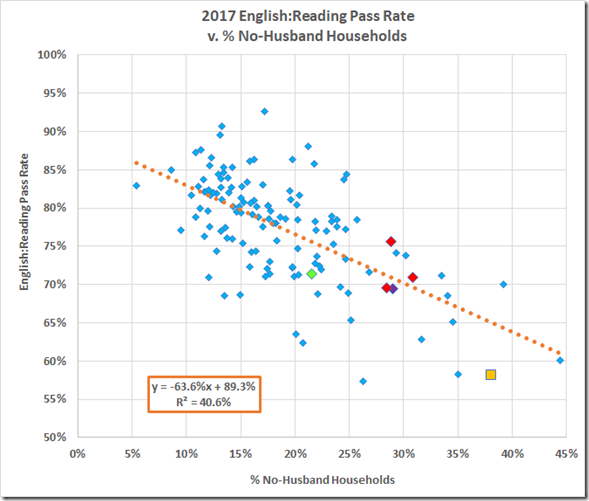

We know that the percentage of “economically disadvantaged” students in a school district is correlated significantly with Standards of Learning failure rates. But is poverty the driver behind low test scores, or is it just correlated with a third factor that is the real driver? Over on Cranky’s Blog, John Butcher ran an interesting analysis: He correlated English reading pass rates in a Virginia school district with the percentage of no-husband households in the jurisdiction. The results can be seen in the graph above. The percentage of no-husband households accounts for roughly 40% of the variability in SOL pass-rate performance.

John was addressing a different issue from the one I am interested in. He was making the argument that school districts should not be judged on raw SOL pass rates. Given the fact that SOL pass rates are strongly correlated with poverty, and even more strongly correlated with the percentage of fatherless children, schools should not be held accountable for their district’s demographics. They should be held accountable for under-performing on a demographically adjusted basis. (Even by that standard, he notes, the City of Richmond schools underperform “atrociously.”)

While I totally agree with the point Butcher is making — schools should be judged on their educational value added, not the demographics of their student bodies — my interest in this post is different. To what extent is the sociological background of Virginia’s students responsible for poor educational outcomes?

The Left wants to put the blame on race and class, the implication being that any deficiencies are the result of an inequitable “system” that stacks the deck against the poor and minorities. I put the blame on sociology, primarily the breakdown of the family structure among lower-income Virginians of whatever race or ethnicity. The problem is not a “black” problem or a “white problem” but a “social breakdown” problem. It only appears to be a “black” problem because the disintegration of traditional family structures is more prevalent in the black lower class than the white lower class, though not by much.

I contend (hardly an original idea) that intact families tend to create a more stable, more nurturing environment to raise children, and that children raised in intact households are far more likely to do well at school. The presence of the biological father is crucial. That’s not to say that there aren’t awesome step-fathers who fill the paternal role, and it’s not to say that some fathers, who are drunkards or substance abusers, can’t be awful. It’s not to say that absent fathers can’t play an active role in their children’s lives. It’s not to say that some single moms with powerful personalities can’t mold their kids into successful human beings with no help from anyone else. But it is to say that the odds increase exponentially that kids will grow up in a toxic environment when there isn’t a father figure to protect them, love them, and enforce discipline. Many kids raised in this toxic environment suffer physical and emotional abuse, which gives rise to severe emotional problems later on — emotional problems that lead to “acting out” in school and poor academic performance.

The odds of poor academic performance increase, I hypothesize, if the family lives in a poor neighborhood where other kids have escaped the ability of their single mothers to control their behavior, where criminality is rampant, and where peer pressure lures adolescents into a “street culture” that devalues education. Even students who haven’t suffered physical or emotional abuse can bring their street culture of defiance and disrespect of authority into the schools.

Why does this matter? It matters because misdiagnosing the problem as systemic racial and economic inequity leads to a set of solutions — essentially, the solutions that are rapidly becoming institutionalized in Virginia’s school systems today — that geared to… redressing racial and economic inequities. If the premises of those solutions are wrong, the solutions will not work. Indeed, the putative remedies might even harm the children their advocates purport to help.

Perhaps I’m wrong and the social justice advocates are right. Perhaps we both have seized upon a piece of the truth. Fortunately, Virginia has a mechanism — the Standards of Learning tests — by which we can test our different views of the world. We should gain access to a new year’s worth of SOL results in a couple of months. We shall see. We shall see.