Correlation does not equal causality. That’s a fundamental tenet of statistics, but the concept apparently is so rarefied that a Virginia Mercury article based the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s County Health Rankings appears to be unfamiliar with it. The result is a headline — “In Virginia, health outcomes follow geographic and racial lines” — that has become standard fare in the ongoing Oppression Narrative embraced by most of Virginia’s media outlets. By misdiagnosing the problem, the Oppression Narrative does a grave dis-service to Virginia’s poor and minorities.

Writes the Virginia Mercury today:

More than 20 percent of Virginia’s black, American Indian and Hispanic populations report poor or fair health, compared to 14 percent of the state’s white residents. …

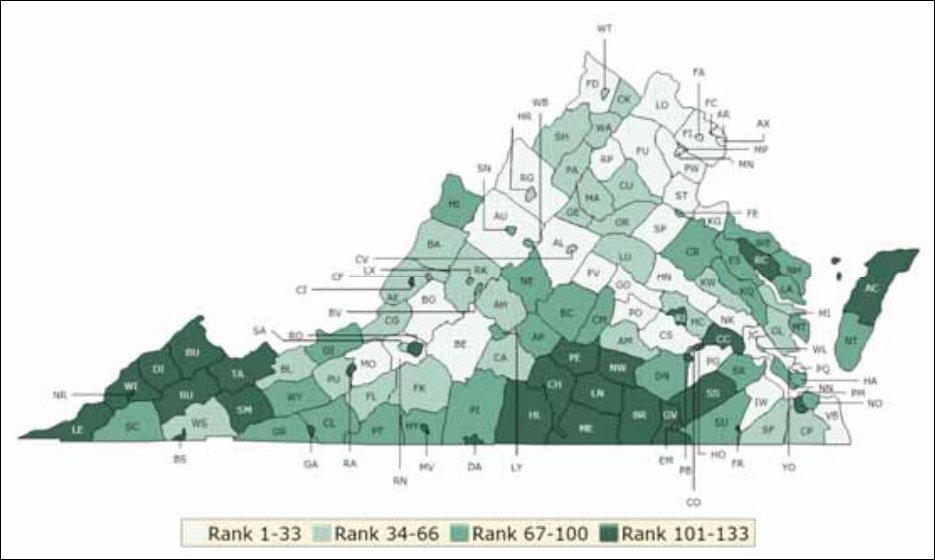

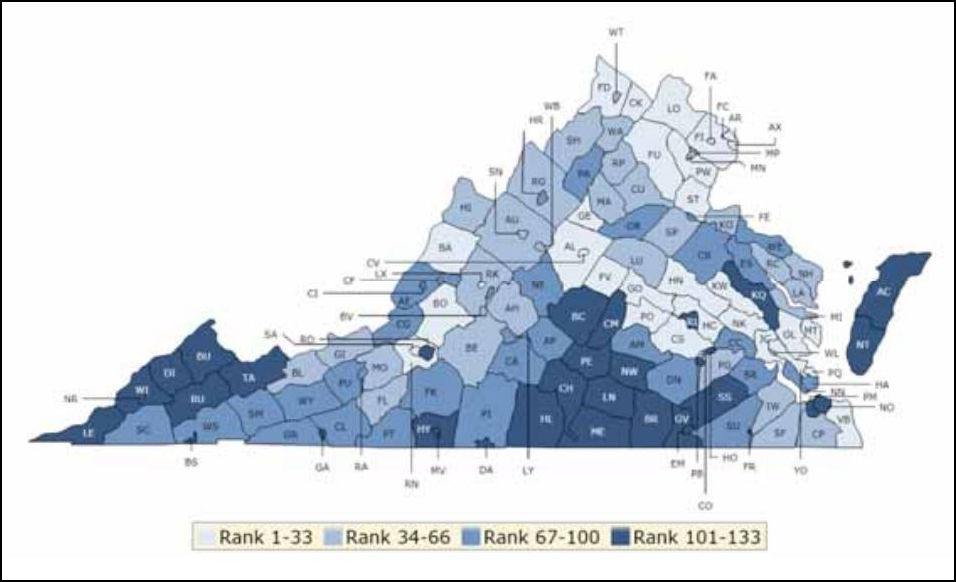

Year over year, the rankings essentially tell the same story: Virginia’s healthy counties, many of which are nestled in the northern part of the state, remain healthy, while its unhealthy localities, clumped together in the south and southwest, continue to struggle with poor outcomes. …

The article continues:

“There are significant differences in health outcomes according to where we live, how much money we make, or how we are treated,” the report states.

“There are fewer opportunities and resources for better health among groups that have been historically marginalized, including people of color, people living in poverty, people with physical or mental disabilities, LGBTQ persons and women.”

To be sure, there are differences in access to health care that vary by geographic area. As a rule, access is better in Virginia’s affluent metropolitan areas than it is in poor rural areas. However, it is not clear from the Robert Woods Johnson Foundation (RWF) data how much of better health can be attributed to differences in access to treatment and how much to differences in the prevalence of risk factors such as obesity, diabetes, smoking, substance abuse, and unsafe sex.

The RWF reports discusses those factors at some length. The Virginia Mercury article totally ignores them. But even the RFW methodology has problems. We must delve into the details in order to see how the presentation of statistics can be more biased than readily meets the eye.

The RFW health factors ranking is weighted as follows:

- 30%: health behaviors (tobacco use, diet & exercise, alcohol & drug use, sexual activity);

- 20%: clinical care (access to care, quality of care);

- 40%: social and economic factors (education, employment, income, family & social support, community safety); and

- 10%: the physical environment (air & water quality, housing & transit).”

The RWF’s methodology obscures a very important distinction: How important are factors based on health behaviors versus factors based on social and economic conditions? Smoking, poor diet, lack of exercise, and unsafe sexual activity are activities over which individuals have considerable control. They also vary by level of income and education. But it’s not the income or education that causes the negative health outcomes, it’s the behavior itself.

The RFW ranking model gives behavioral factors a 30% weight in its health factors ranking, but it’s not clear why the researchers picked that number. Do county-level differences in behavorial factors account for 30% of the variability in health outcomes? Or is the weight assigned arbitrarily?

For example, it is commonly accepted that people who smoke are more likely to suffer health problems. Higher education correlates with higher incomes and less smoking. According to American Health Rankings, in Virginia 31.2% of people with less than a high school education smoke, compared to 6.2% who are college grads. What causes the better health come: the bigger paycheck or the lower rate of smoking?

Another example: The Virginia Mercury notes that Virginia blacks have a higher rate of low-birthweight births than other races/ethnicities: 13% for blacks compared to 7% for whites and Hispanics, and 8% percent for American Indians and Asians. The article doesn’t come right out and say that black babies have lower birthweights because of their mothers’ unequal access to health care, but in the context of the article, that’s the clear implication.

An academic article, “The Risks Associated with Obesity in Pregnancy,” finds a link between a mother’s obesity and low birthweights. “An estimated 11% of all neonatal deaths can be attributed to the consequences of maternal overweight and obesity.” In Virginia, according to The State of Obesity, 41% of blacks were classified as obese in 2017 compared to 28% of whites.

The aforesaid article notes that “the risks associated with obesity in pregnancy cannot necessarily be influenced by intervention.” Preventive measures to normalize body weight before a woman becomes pregnant are the only way to budge the statistics. In other words, it gets complicated.

One more example: Reckless sexual behavior leading to sexually transmitted diseases falls into numerous categories, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: exchanging drugs/money for sex, having sex while high/intoxicated, having sex with a person who injects drugs, having sex with anonymous partners, meeting sex partners through the Internet, and having sex with multiple partners. Nationally, the rate of STDs is significantly higher among blacks than whites. (I could not find specific numbers for Virginia.) The CDC argues that part of the racial/ethnic variability may be attributable to differences in access to health care, which allows the diseases to be treated and partners notified, but even that observation comes with a caveat:

Even when health care is readily available to racial and ethnic minority populations, fear and distrust of health care institutions can negatively affect the health care-seeking experience. Social and cultural discrimination, language barriers, provider bias, or the perception that these may exist, likely discourage some people from seeking care.

Yeah, it gets complicated.

Why does this matter? It matters because if you accept the Oppression Narrative, you focus your efforts on changing social and economic variables such as the inequality of education, housing, and income. Conversely, if you believe that negative medical outcomes are due in significant measure to individual choices, you focus on getting people to adopt healthier behaviors. By misdiagnosing the problem and causing a misallocation of resources, the Oppression Narrative hurts those whom its purveyors purport to help.