by James A. Bacon

A key cost driver at the University of Virginia is the increasing size and declining teaching productivity of its faculty. The topic appears to be taboo.

The Board of Visitors hasn’t discussed it, and there is no indication from publicly available sources that the university administration has engaged in any introspection. The slender evidence available to the UVa community is found on the website of UVa’s office of Institutional Research & Analytics (IR&A), a 17-person office deep within the bowels of the university. While that office does publish limited data online, it has not released any reports of an analytical nature.

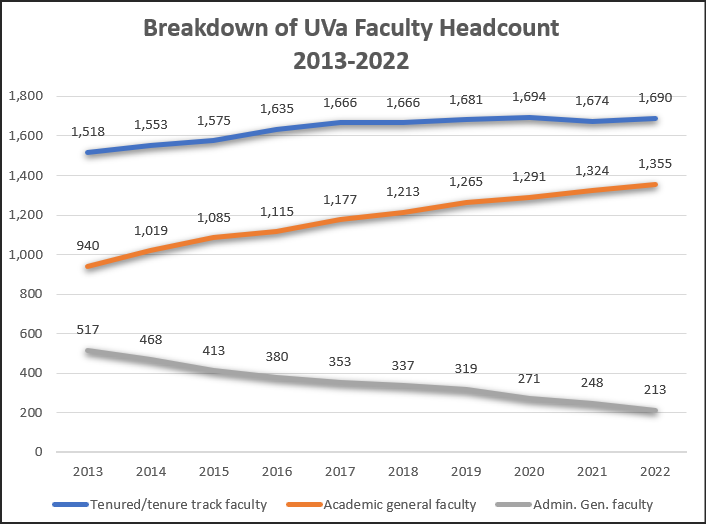

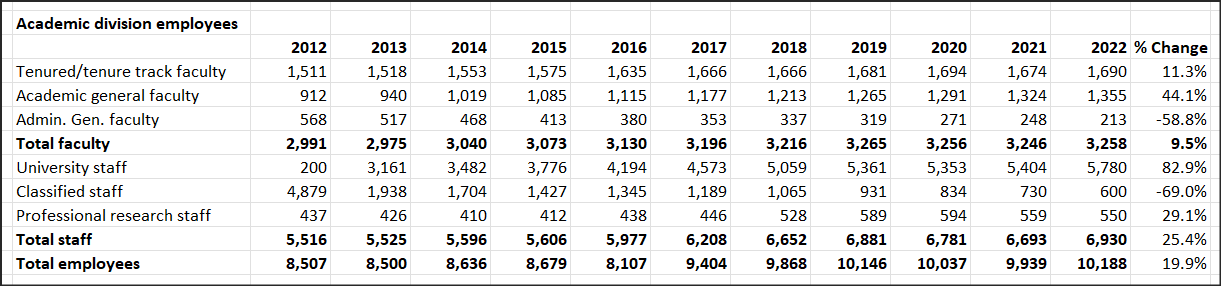

Employee salaries, wages and benefits comprise roughly half of the university’s cost structure. While a 25.4% surge in salaried staff accounts for much of the growth in UV’s cost structure between fiscal 2012 and fiscal 2022 (see our article, “Hard Numbers on Administrative Bloat“), a 9.5% increase in “faculty” was a significant contributor as well. If we count teaching faculty only (tenure-track professors, lecturers and instructors) and exclude departmental-level administrators, whose numbers have been slashed, the “faculty” headcount bounded ahead by 25.7%.

By contrast, annualized FTE enrollment rose 8.8%.

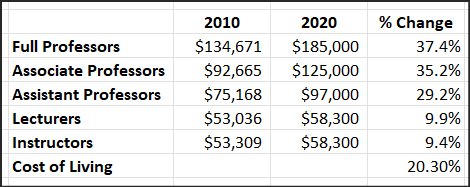

Headcount doesn’t tell the whole tale. It also matters what employees get paid. And therein resides another interesting story. There is a two-tier hierarchy at UVa, as there is in most of academia. Tenure-track professors, comprising the academic aristocracy, saw salaries increase significantly faster than inflation over the past 10 years. Instructors and lecturers, constituting an academic proletariat typically employed in one-year-contracts, lost ground to inflation. Here is a summary of how the various academic ranks fared between fiscal 2012 and fiscal 2022:

Cost of Living calculated between July 2011 and June 2021.

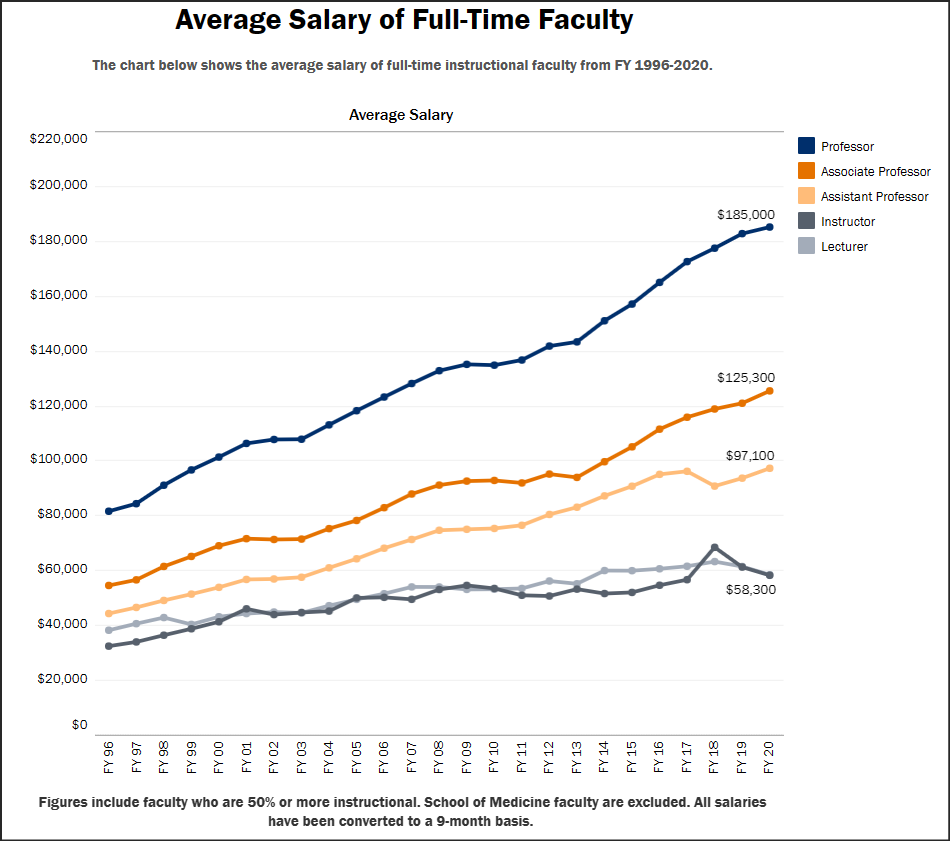

This graph, taken directly from the IT&A website, shows the trendlines over a longer period of time. One might say that UVa’s faculty is emblematic of the growing income inequality so often decried by… UVa faculty.

Graphic source: office of Institutional Research & Analytics

The following table shows employment headcount for three categories of faculty — tenure-track faculty, general faculty (instructors and lecturers), and administrative general faculty — as well as various categories of salaried staff.

To view a more legible version of this table, click here.

UVa’s long-standing practice since fiscal 2012 has been to squeeze administrative support for faculty at the departmental level, exercise modest discipline in the hiring of tenure-track faculty, and ramp up the hiring of instructors and lecturers. Put another way, UVa has been relying increasingly upon lower-paid, short-term faculty members, throttling their compensation over time while funneling generous pay raises to tenure-track faculty.

This high-altitude view might hide sub-trends that could put a different color on things. For example, while the data show that full professors enjoy the highest and fastest-increasing pay on average compared to other groups, we don’t know if pay raises for most full professors are comparable to those for the lower orders. The average number could be skewed by a few highly paid super-stars whose pay is supplemented by endowed chairs or other remunerations. Further study is desirable before drawing hard conclusions.

While some matters could stand greater clarity, the data strongly suggest that UVa has a faculty productivity problem. Remember, enrollment increased only 8.8% over this period. If we exclude “administrative” faculty (on the grounds that secretaries and administrative assistants don’t teach), then the ranks of UVa’s faculty increased by 25.7%. Adjusted for the slight increase in enrollment, it took 15.8% more non-administrative “faculty” to teach the same number of students. If class sizes were shrinking commensurately, then it might be claimed that faculty are teaching smaller, more intimate classes. That is an empirical matter that should be easy enough to resolve… if the UVa administration were interested in finding answers.

But a very different scenario seems more likely to be true. A case can be made that UVa has been shifting the teaching workload from UVa’s academic aristocrats, who tend to place a higher value on career-advancing research and writing than teaching, to instructors and lecturers. Instructors commonly teach three or four classes per semester, senior faculty only one or two.

Another factor worth exploring is the degree to which administrative authority has shifted from faculty departments to UVa’s salaried bureaucracy. Time was, faculty departments were largely self-governing and autonomous. But UVa, like other higher-ed institutions, has been centralizing power in the hands of administrative staff who are even more cosseted, highly paid, and hierarchical than the professoriat. Whether this evolution has resulted in more administrative work or less for faculty members remains an open question. On the one hand, faculty may have dished off some mundane chores to staff. On the other hand, the multiplication of administrators seeking to justify their existence may have resulted in more busy work. The latter possibility can be seen in the “Inclusive Excellence” mania that has plunged departments into bouts of self-flagellation and corrective measures over their self-professed racism.

The escalating cost of attendance should be an all-consuming preoccupation of the Board of Visitors. Any discussion about affordability needs to begin with a hard-nosed look at UVa’s bloated administrative staff and declining faculty productivity. Ignoring those topics, as past boards have done, represents a dereliction of duty.

Correction: This article has been updated to correct an erroneous statement in the original version that student enrollment increased only 1.1% between fiscal 2012 and fiscal 2022. The correct figure was 8.8%.