by James A. Bacon

It may be time for a major re-think of transportation policy. Alan Pisarski, a Northern Virginia transportation consultant, argues that the states should refrain for now from expanding the transportation system and dedicate funds to properly maintaining the transportation assets they have.

New technologies and business models, some accelerated by the COVID-19 epidemic, could radically change decades-old travel patterns. In a Reason Foundation presentation made last year, Pisarski said the level of uncertainty is “immense.”

Virginia legislators would do well to review Pisarski’s presentation as they tinker on the 2022-23 budget bills advancing through the General Assembly. Absent major changes, the commonwealth will allocate $8 billion roads and highways, almost $1 billion to rail and mass transit in fiscal 2022, and even more the following year. That includes $3.6 billion for new highway construction and $700 million for mass transit (mostly to support the Washington Metro). Spending is up dramatically from the $7.2 billion allocated to transportation in fiscal 2020. Fixated on social justice issues, legislators have been content to let the system run on auto-pilot, with funds allocated between maintenance, road construction, and transit investments according to complicated formulas. The larger issue of how much money Virginia really needs has gone unaddressed.

For years, Virginia transportation policy played catch-up with the wave of post-World War II growth, a land-intensive pattern of development commonly referred to as “suburban sprawl.” Driven by the real estate-development lobby, transportation policy effectively subsidized low-density, hop-scotch development that left the suburbs dependent upon automobiles for transportation. The 2007 sub-prime mortgage debacle sparked a backlash in favor of higher-density, mixed-use development that could be served by mass transit. Then along came COVID-19. Commuters abandoned mass transit in droves, devastating the finances of transit authorities. And more people than ever began working at home.

In his presentation, Pisasarski devotes considerable time to examining the Work At Home (WAH) trend. The big question: Will the WAH home snap back to normal once the epidemic recedes, or will the adoption of telecommuting prove permanent?

I would add more uncertainties. How will commuting patterns change when people can work or play on their computers while cars drive themselves? Will the widespread adoption of Electric Vehicles encourage more driving or discourage it? Has the Uber ride-hailing model peaked, or will it revive post-pandemic? Will mapping apps encourage people to stitch together automobile ride-hailing with buses, trains, biking and walking, or will multi-modals trips remain a pipe dream? Will the mobility-as-a-service (MAAS) concept, in which subscribers subscribe to transportation capacity as an alternative to owning their own cars, ever catch on?

Nobody knows.

“The one certainty,” Pisarski says, is that “people will continue to travel. How much, why, when, where, how is absolutely unclear.”

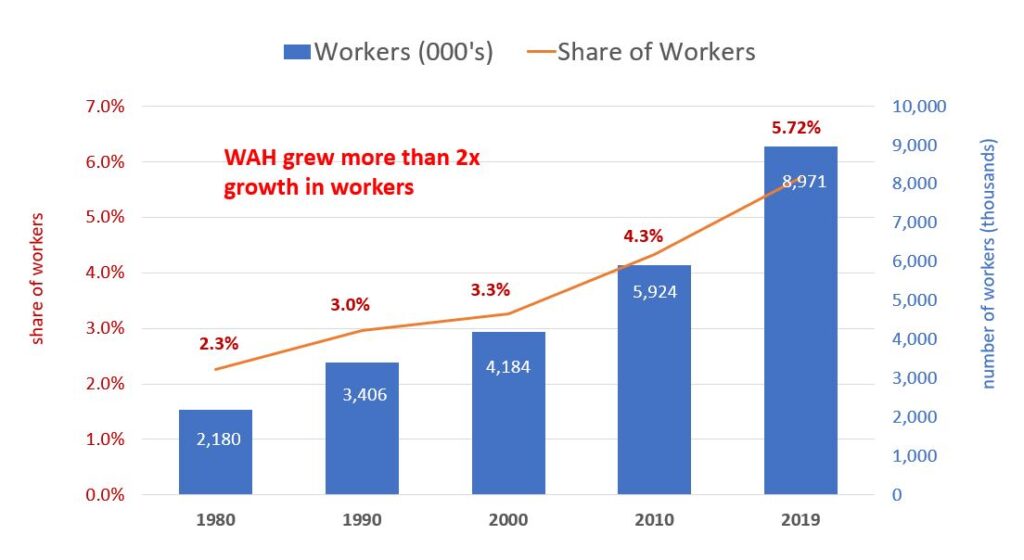

A near-certainty is that the Work At Home trend has reached critical mass. Thanks to the Internet and numerous technologies that use the Internet, WAH has grown steadily since the 1980s. Starting from a low base — 2.3% of workers in the 1980s — that growth had only a modest impact on travel and commuting trends. But the rate of increase is accelerating, as can be seen in Pisarski’s graph atop this post, reaching 5.72% in 2019. Over the three decades displayed, WAH grew twice as fast as the workforce.

COVID intensified the WAH trend. In the past, employers resisted allowing employees to work at home where they could not be strictly supervised. Compelled by the epidemic to allow employees to stay away from the office, major employers have found in many instances that WAH actually boosts employee productivity.

The key distinction, Pisarski says, is between people who can work with communications tools versus those whose jobs require a physical presence to interact with people or things. In an increasingly knowledge-based economy, people who can work remotely comprise an increasing share of the workforce.

As more people work home, they will take fewer trips, a trend that will affect all transportation modes: driving alone, carpooling, mass transit, perhaps even walking and biking.

The WAH phenomenon will involve mainly higher-income workers. It will not affect lower-income jobs based on interacting with people (restaurants, haircutteries, hotels) or requiring hands-on interaction with machines and goods (manufacturing, warehousing, stores). To address the transportation needs of lower-income workers, he suggests, public policy should focus on private-sector solutions:

- Vans, small bus-based systems, public/private fleets, car rental vans, hotel vans, church vans, Microsoft buses.

- Super shuttles

- Company vans for employees (like the 3M commute-a-van program)

- Mobility as a Service concepts

“Open the system up,” Pisarski says. “Utilize disruptive technologies that can rapidly serve users’ needs.”