by James A. Bacon

State Certificate of Public Need (COPN) programs come in many shapes and sizes across the United States. Fourteen states have abolished the health-care regulatory program entirely, while states that continue to regulate capital investments in health care facilities and high-end equipment vary widely in what they regulate.

Among states with COPN, Virginia regulates about 19 of 30 categories of medical services, placing it in the middle of the pack for regulatory intensity, according to a state-by-state comparison presented to Virginia’s COPN work group earlier this month. Virginia’s application fees are relatively modest, but the review process, at 190 days, is the longest in the country.

The work group is studying Virginia’s COPN law to determine if it needs reform, in light of the enactment of the Affordable Care Act and other changes in the medical marketplace. The justification for COPN when it was instituted nationally in Virginia in 1973 was that normal competitive processes did not work in health care. When hospitals and other providers added hospital beds and purchased high-tech equipment, they supposedly made sure that patients utilized them, which added to the run-up in health care costs.

However, critics of COPN argue that the cost-plus system for reimbursing providers, which created financial incentives for providers to over-diagnose and over-treat patients, is no longer prevalent. The primary justification cited now for COPN is that by restricting competition, it shores up hospital profits and guarantees as a condition of receiving a certificate that hospitals will provide charity care for thousands of Virginians lacking insurance.

Virginia Secretary of Health and Human Resources Bill Hazel explained the logic of the national survey this way: “Do we know anything about … what actually happens in states where there has been deregulation?” (See the Richmond Times-Dispatch coverage here.)

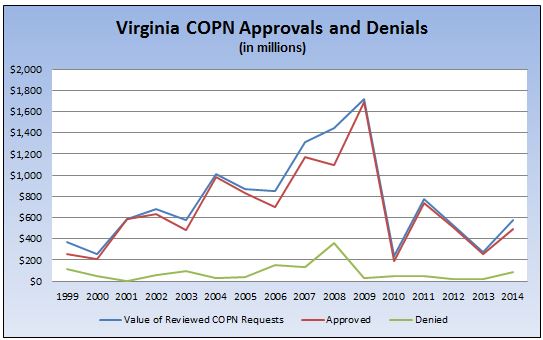

Those are worthwhile questions to start with, but the study group needs to delve a lot deeper. One question I would ask is this: Does Virginia’s COPN really accomplish anything? The chart above, based upon Virginia Department of Health data, shows the dollar value of COPN applications approved and denied. Virginia approves the overwhelming majority of applications, a trend that has become especially evident since 2009. If the COPN reviews are just rubber-stamping applications, what’s the point in reviewing them at all? Alternatively, does the COPN process discourage entrepreneurs from even submitting proposals to a process they deemed to be rigged in favor of established players?

The chart raises another question: What accounts for the dramatic fall-off in health care-related capital spending in Virginia since 2009? We can’t blame it on the 2007-2009 recession, a period during which hospital spending actually peaked. Arguably, spending tanked as a reaction to uncertainty created by the enactment in 2010 of the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare). But even that explanation begs another question: Why has capital spending remained so low in subsequent years when regulations have been written, the law applied and uncertainty is less prevalent? Have Obamacare or changes in the commercial health insurance market created incentives to restrain capital spending? And, if so, why would we still need COPN?

I would add an even more fundamental set of questions: What impact has COPN had on health care productivity in Virginia? The health care sector is notorious for its low level of productivity growth, an underlying cause of escalating health care costs. There are two schools of thought. The first is that maximizing utilization of a restricted supply of beds and equipment, which COPN is designed to do, will lift productivity. The countervailing theory is that the path to greater productivity lies in embracing new processes, which often entail redesigning the physical layout of hospital floors or even building specialized, dedicated facilities. COPN would slow such changes. Which school of thought is right? Without more evidence, we don’t know.

The debate over U.S. health care focuses overwhelmingly on who pays. It’s a zero-sum game of slicing up a fixed pie so that some get bigger pieces and others get smaller pieces. The only way out of this morass, to borrow a hoary cliche, is to grow the pie — to make more health care available at more affordable prices for all. One way to do that is to overhaul the way health care is delivered: to evolve from a system dominated by general-purpose hospitals that provide a wide range of services to one that includes focused factories specializing at performing a narrow range of procedures exceptionally well and exceptionally efficiently.

That’s not happening. Rather than encouraging entrepreneurial specialization and experimentation, the health care industry is consolidating. Both the insurance and hospital sectors are becoming cartels, and they’re absorbing independent physician practices. The causes are bigger than COPN alone. But COPN may contribute to the trend. The big-picture question Virginia policy makers need to ask is this: Do we want cartels or entrepreneurs to dominate state health care? I don’t hear anyone asking that question.