by James A. Bacon

Bacon’s Rebellion readers can’t seem to agree on much when it comes to the COVID-virus, but there is one area of consensus: Virginia needs to perform more testing. The Old Dominion ranks 12th in the nation for population (8.6 million) but only 22nd as of March 27 for testing. Only one in 714 Virginians had been tested, compared to one in 113 New Yorkers. If you don’t think New York makes a fair comparison — it is, after all, the epicenter of the virus in the U.S. — consider Maryland, where one in 410 people have been tested.

Virginia media have addressed the testing issue sporadically, but no clear narrative has emerged regarding why has the state done so little testing relatively speaking. I don’t draw firm conclusions in this post. Rather, my goal is to begin surfacing information and exposing it to the rapier-like logic and web-researching skills of readers for closer analysis.

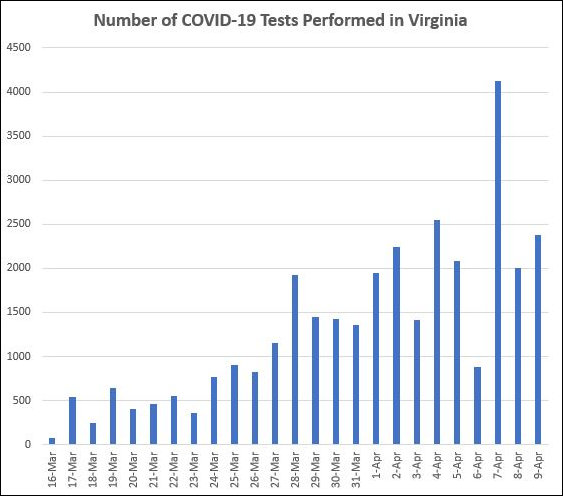

As a starting point, let’s determine how much testing is actually occurring. After a dismal start, less than 500 tests per day in mid-March, the number of tests has reached a level of 2,000 per day. (Statistics were skewed over the weekend due to delayed data collection by the Virginia Department of Health, which caught up with the numbers Monday.) This level of testing may be under-stated in the official numbers due to the increase in testing at private labs, which can take a week or more to return results. As those tests dribble in, the testing numbers could well increase.

Still at this rate, as fellow blogger D.J. Rippert has pointed out, it would take 4,300 days or about 11.8 years to test every Virginian. We need more tests.

So, who does the testing?

The state lab. Back on March 15, Dr. Denise Toney, director of the state’s Division of Consolidated Laboratory Services, said the state lab could perform tests on 370 to 470 people. The state lab did not have its own capability to create test kits. It was dependent upon the kits it received from the Centers for Disease Control. As of March 15, the state was anticipating getting two more kits (with 500 reaction tests each) from the CDC. The state lab can’t do any more testing than the number of its it receives from the CDC, and it appears that the CDC prioritizes its distribution of testing kits on the basis of need. At present, New York is the 800-pound, virus-infected gorilla. People are dying there in frightful numbers. So, it’s no surprise that New York is getting the silverback’s share of kits. That’s the way it is. If Virginia public health authorities want more tests, they will have to find a way themselves.

UVA Health. Acting on the initiative of two lab technicians, UVA Health developed its own testing platform. As of March 25, the health system said it was capable of performing more than 200 tests per day. It was reserving 150 for its own patients but willing to perform 50 tests days for others. UVA Health has been accepting private donations, which it has used to expand its testing capabilities. I have seen no recent update on its current capacity.

Sentara Healthcare, the dominant health system in Hampton Roads, announced the launch of an in-house testing capability on April 6. The healthcare giant had grown frustrated with the lengthy delays — 10 days or more — for private tests to be returned. “The goal,” stated a company press release, “is to incrementally achieve the capacity to complete 1,000 tests per day within a few weeks and return test results in 24 to 48 hours.”

Sentara’s newly created lab is located at Sentara Norfolk General Hospital, the largest hospital in the region. Norfolk General also is affiliated with the Eastern Virginia Medical School (EVMS). Did EVMS play a role in developing the capability? The Sentara statement did not say.

VCU Health. On March 25, VCU Health System announced that its physicians had developed their own COVID-19 tests in a pilot program. The WCVE article from which I drew this information did not say how many tests VCU would be able to deliver, only that “VCU Health says they will further develop its in-house testing capabilities and aggressively pursue several diagnostic testing options to meeting the testing demands.” The health system also said it will continue to administer tests in collaboration with private and public state health labs.

I have checked the websites of Virginia’s other big hospital chains — Inova in Fairfax and Carilion Clinic in Roanoke, in particular, and have found no indication that they have developed in-house testing capabilities.

Private labs. In early February, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) cleared the regulatory barriers barring commercial labs from performing COVID-19 tests. The industry promptly began ramping up testing, and now accounts for about 85% of all testing nationally — about 84,000 in one day, March 24. But there are logistical bottlenecks to increasing capacity. Wrote Julie Khani, president of the American Clinical Laboratory Association:

In order to continue to increase capacity, all laboratories must have predictable and consistent access to swabs, personal protective equipment, test kits, reagents and other supplies necessary for testing. We are also working closely with our manufacturing partners who produce the high-throughput platforms that are essential to further expand testing capacity. For laboratories processing thousands of specimens a day, having additional platforms available can help boost daily capacity, a shared goal for our industry and our public health partners.

Presumably, health systems and public labs face the same challenges. Given limited capacity, the industry has been seeking federal guidance on how to prioritize those most in need. Said Khani in a separate letter: “Laboratories perform, but do not order testing; we rely on the expertise of our partners in hospitals and physician offices.”

It is not clear to me what options the Northam administration has to increase the number of tests in Virginia. Both the CDC and private labs are prioritizing testing on the basis of “need,” and Virginia has not yet been classified as a hotspot, so the state’s need is low compared to disaster zones like New York City. The most promising avenue, it seems, would be to ramp up testing at Virginia’s three medical school-affiliated health systems. Even better, perhaps the state lab should develop its own testing capability. I have seen no indication whether the Northam administration is coordinating with these key institutions.

I have submitted an inquiry to a VDH spokesperson regarding Virginia’s testing capacity and, specifically, what the VDH has done to augment that capacity. I will update readers if I get a response.