Yeah, yeah, another UVa post. Think of it this way: the governance issues at UVa are similar to those of every public university in Virginia.

by James A. Bacon

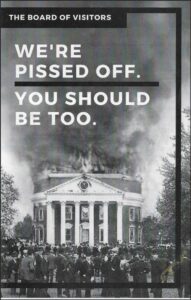

In past posts The Jefferson Council has highlighted a recently published screed, “We’re Pissed Off; You Should Be Too,” that criticizes the governance structure of the University of Virginia. Among other grievances voiced, the authors note that state government provides only 11% of the funding for UVa’s academic division, yet the state controls the appointment of 100% of the board seats. The governance structure should be more “democratic,” they contend. Students and faculty should be given voting seats on the board.

“Currently, the BOV oversees 28,361 employees, as well as 23,721 undergraduate and graduate students. There are only 3 ways a BOV member can be removed, and none of them involve us,” laments the tract. [Emphasis in the original.] “The only apparatuses that have power over the BOV are other BOV members and the governor.”

Message to UVa lefties: the Board of Visitors is accountable to the citizens of Virginia — not you. You are employees, not owners. The Commonwealth of Virginia owns UVa, and the governance structure is designed to serve the citizenry, not university employees.

UVa is one of 15 public four-year colleges in Virginia. (Another is the University of Virginia-Wise, a small institution that is also governed by the UVa Board of Visitors and whose revenues and expenditures are lumped in with UVa in its financial reports.) Unlike some states, such as North Carolina, Virginia’s university system is decentralized. The State Council of Higher Education for Virginia (SCHEV) is mainly a coordinating body that maintains statistics, issues reports, and seeks to ensure that Virginia’s free-wheeling two- and four-year institutions don’t needlessly duplicate effort.

Virginia’s system of higher education serves citizens by preparing them for employment and civic life. To advance those aims the Commonwealth funnels yearly appropriations to its public colleges and universities, floats tax-privileged bond issues to underwrite building programs, subsidizes R&D activities, and allocates supplementary funding to academic programs deemed essential for a growing economy. The University of Virginia is an agency of the state government. It would make no more sense for UVa to function as a “democratic” institution than it would for the Department of Motor Vehicles, the State Police, or the state Medicaid program to do so.

The flaw in UVa governance is not that it is insufficiently democratic, it is that the university is too responsive to faculty and administrators, and not attentive enough to its intended beneficiaries: students and their tuition-paying parents. The administration dominates. For years the Board of Visitors has functioned as cheerleader for the ambitions of a succession of UVa presidents, including in recent years John Casteen, Teresa Sullivan and Jim Ryan.

(Occasionally, powerful rectors emerge. The Board broke from its passivity when then-Rector Helen Dragas forced Sullivan’s resignation. But Sullivan battled her way back into power, and Dragas and her board allies were chastened. With his dominating personality, hospitality-industry entrepreneur William H. Goodwin kept a close watch on spending. But he did not change core priorities.)

The interests of senior administrators are ill-aligned with those of Virginia’s citizenry. It is useful to view UVa as a prestige-maximizing institution driven not by the quest for profit but for status in the higher-ed community. UVa is locked in an endless arms race to gain in status compared to its peers. UVa’s administrators and board members aspire to reach Ivy League levels of renown. That means hiring celebrated faculty members who lend luster to the institution, erecting starchitect-caliber buildings, building the endowment, bolstering the level of sponsored R&D, and polishing the university’s image in the world beyond academe. In the past the prestige imperative also meant recruiting students with the highest SAT scores, although with the rise of wokeness, status is increasingly conferred upon institutions with preferred demographic profiles.

UVa, like other elite institutions, is run primarily for the benefit of an elite comprised of senior administrators (recruited mostly from other top universities) and tenured faculty. Administrators’ desiderata are adopted as the university’s priorities. Mission creep sets in. The number of Diversity, Equity & Inclusion administrators proliferates. Resources are allocated to making UVa “great and good” by exporting the university’s preoccupations with social-justice and climate change into the community at large. The bureaucracy absorbs an ever-bigger share of expenditures. That which cannot be funded by hiking tuition, fees, room, and board is raised from alumni by touting shiny objects such as building projects, the endowment of new programs, and the hiring of star faculty.

Administrators get to enlarge their bureaucratic turf and advance their ideological goals, and elite faculty are awarded with cushy contracts, endowment-supplemented salaries, and minimal teaching responsibilities. Non-tenured instructors and graduate students stand at the bottom of the academic hierarchy as contingent employees who are paid less to teach more. It’s not clear that students benefit at all.

That is the system that the authors of “We’re Pissed Off” are railing against. That system is not the invention of Bert Ellis, the Board of Visitors member who is the object of their venom. To the contrary, Ellis wants to root out bureaucratic excess that soaks up dollars that could go to lower tuition or higher wages. If the authors of “We’re Pissed Off” would take off their ideological blinders, they might understand that.

James A. Bacon is executive director of The Jefferson Council, an organization of UVa alumni.