by Steve Haner

Appalachian Power Company (APCO), serving Western Virginia, has now filed its annual update on Virginia Clean Economy Act compliance, including long term bill impact estimates. As the State Corporation Commission begins its review process, here are some highlights:

- The projected increases in electric bills are little changed and perhaps a bit lower than those reported a year ago. The cost for 1,000 kilowatt hours to power a home for a month was $117.09 in 2020; using the compliance plan the company prefers, it is projected to be $172.12 in 2030 (up 55%) and $193.29 (up 65%) in 2035.

- Despite all the political discussion about Virginia turning to the new, smaller nuclear reactor technology (so-called small modular reactors, or SMRs), they don’t turn up in APCO’s development plan as even an option for a long time, perhaps in 2040 when its major West Virginia coal plants will retire. Dominion Energy Virginia’s preferred VCEA compliance plan also didn’t turn to SMRs in the short term.

- Energy demand projections within Appalachian’s territory are negative, going down. Over the next 15‐year period (2023‐2037), its service territory is expected to see population decline at 0.3% per year and non‐farm employment growth of ‐0.1% per year. It projects its customer count to decline by 0.1% over this period. Internal energy requirements and peak demand are expected to decline by 0.4% per year through 2037.

- Appalachian has only one remaining fossil fuel plant within Virginia, a natural gas plant opened in 1958 and expected to retire in 2025. Its main coal plants in other states, however, are slated to stay until 2040. In the meantime, VCEA compliance will require the company to build or enter power purchase agreements for ever-larger amounts of solar and onshore wind power. So far, much of the solar and all of the wind facilities are not located in Virginia but are within the PJM Interconnection footprint, so they qualify for VCEA compliance.

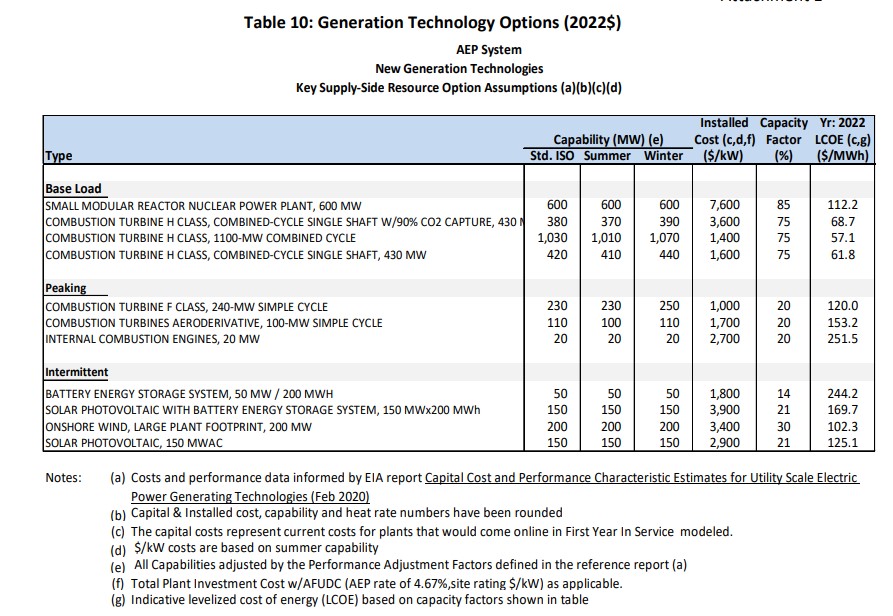

- The summary document, which you don’t need to be an engineer or accountant to follow, includes an excellent table comparing various gas, solar, wind and even the SMR options on the basis of their cost, operational reliability (capacity factor), length of service and cost per megawatt hour (MWH) produced. It is reproduced below.

The company’s estimate is that, as of 2022, electricity from an SMR would cost about $112 per MWH, producing power 85 percent of the time. Compare that to the capacity factor of 21% on solar (based on output from the company’s existing assets) and 30% for onshore wind (also based on experience, not the sales pitches.) Natural gas generation, with or without equipment to capture the CO2 emissions, remains cheaper than the renewable sources, again because it would likely operate 75% of the time.

The most expensive asset illustrated, the small (50MW) battery designed to cover a deficit on the grid for all of four hours, would cost $244 per MWH. The company modeled a future program to add 1,000 MW per year of battery storage to its system, a more realistic amount to cover for intermittent wind and solar generation, but added this comment:

…for the purposes of modeling zero emissions resources to fill the capacity need after the assumed retirement of the (coal) units in 2040, a high cumulative lifetime storage limit was included as a proxy resource at that time. The assumption that 1,000 MW of storage could be added to a Company the size of APCo in any one year, or even cumulatively beginning in 2037 is particularly optimistic.

“Particularly optimistic” is being polite.

In a similar future cost modeling exercise submitted to the State Corporation Commission in late 2022, and reported here March 20, Dominion’s projected residential bill for 2035 for 1,000 kwh was about $20 higher, at $213.36. So, over time a significant gap in electricity costs may develop between Dominion’s and Appalachian’s territories.

The cost projections will change over time as underlying assumptions do, but neither utility is predicting that costs to consumers will be stable or lower because of this transition. VCEA dictates that Dominion’s Virginia customers must receive carbon-free power by 2045 and Appalachian’s service must be carbon-free by 2050. Purchased renewable energy certificates can be part of that compliance.

APCO has 540,000 customer accounts in Virginia, just over half of its total 1 million customers in three states. The list of its current generation assets in the summary document for this filing shows 88% of its total owned generation capacity comes from coal or natural gas. It also has 700 MW of hydro resources from Smith Mountain Lake, Claytor Lake and Leesville Dam, and another 963 MW of purchased power, mostly from outside Virginia.

That list of purchased power agreements includes most of its existing solar and onshore wind suppliers. This pending application (SCC case file here) will mainly add to that list of power purchase agreements (PPAs), with more outside PPAs than company-owned assets. A summary of the application can also be found in the company’s news release on the filing.

The main issue with the previous application was whether the projects then proposed were economically reasonable, and now the SCC staff will begin a similar examination of these projects. That analysis by the SCC’s staff or other stakeholders who might object to some aspect of this application is just getting underway.

The regulatory authorities in the other Appalachian states, West Virginia and Tennessee, face no law similar to VCEA and could reject as imprudent some of these coming wind, solar and battery investments. The plan assumes they will agree, but if they do not, 100% of the costs will fall on customers who live in Virginia.

Unless some future General Assembly or Governor succeeds in actually amending the VCEA, this is the path we face. On the other hand, a future Assembly or Congress could accelerate the planned retirements of remaining fossil fuel plants.

After all, the no-CO2 transition under VCEA is far slower than that demanded by groups like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which just issued another of its annual “this our final warning, do it now or else!” sermons on a predicted climate catastrophe. Dominion and Appalachian burning coal and gas into the 2040s is not what they have in mind.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.