by James A. Bacon

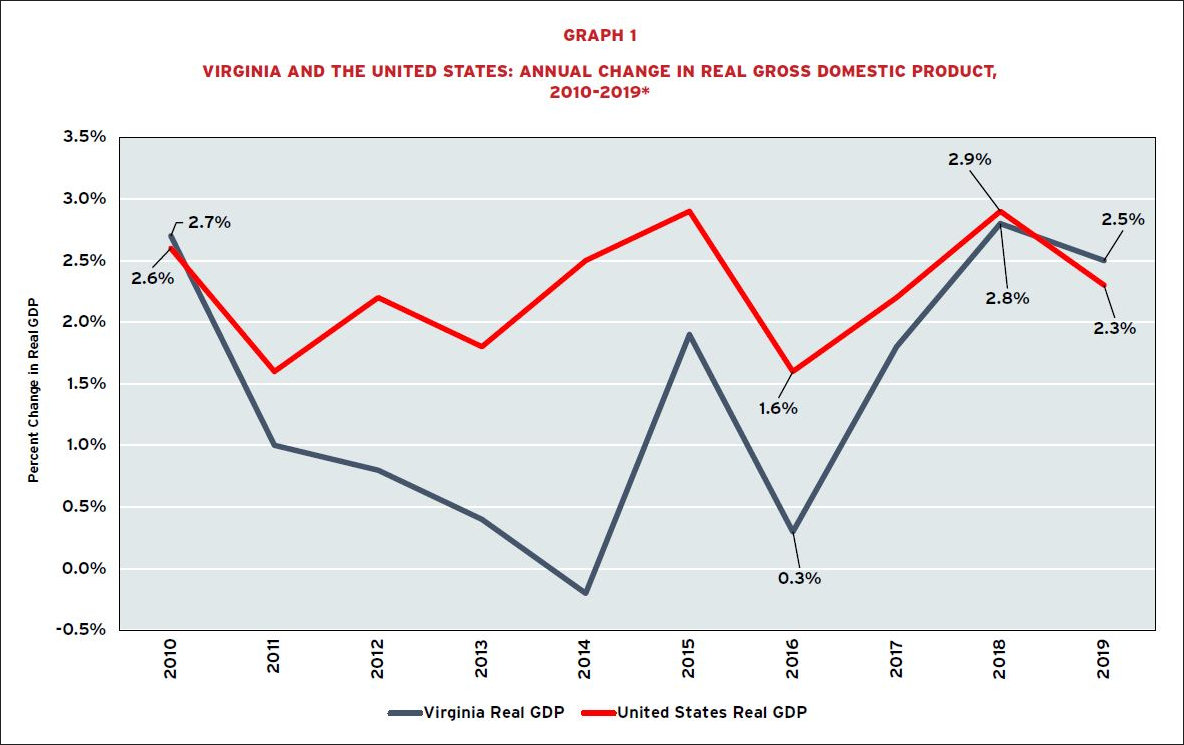

After years of markedly under-performing the rate of U.S. economic growth, Virginia’s economy appears to be approaching national parity, according to data published by Old Dominion University’s “2019 State of the Commonwealth Report.” Indeed, as the U.S. economy slows somewhat this year, the authors expect Virginia to exceed the national rate by a small margin.

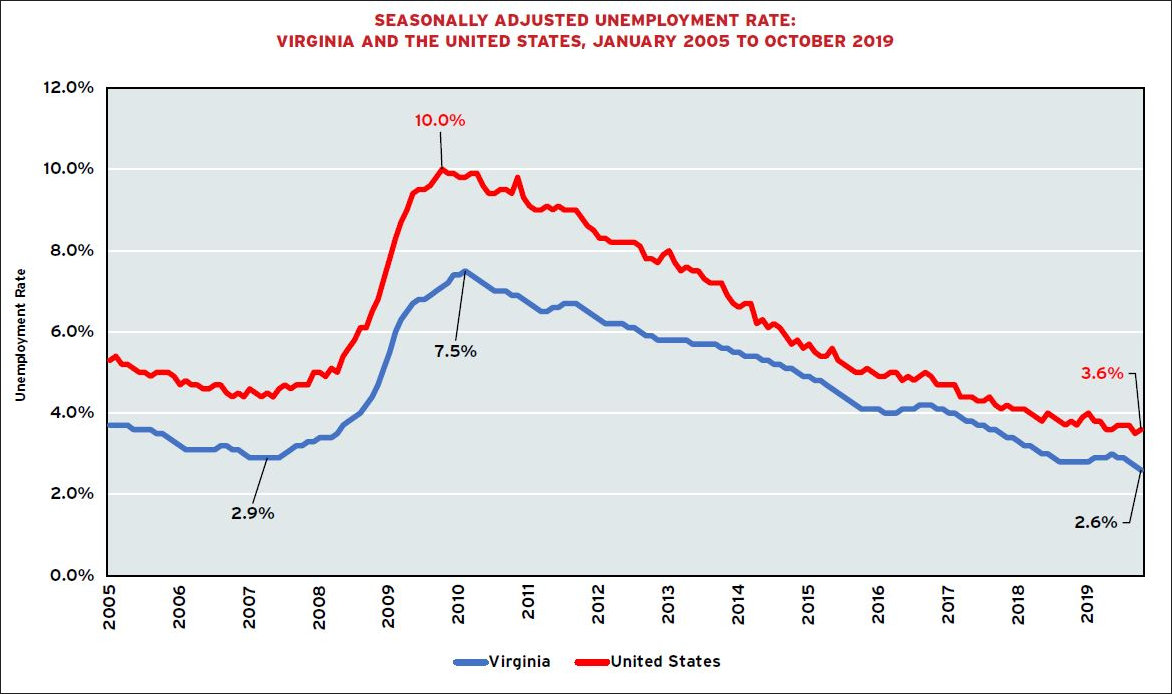

One sign of a vibrant economy is Virginia’s low statewide unemployment rate, 2.6%, significantly below the national rate of 3.6%. The Old Dominion has enjoyed a lower unemployment rate for decades, but as the economy reaches full employment, the gap between Virginia and the national has narrowed in recent years.

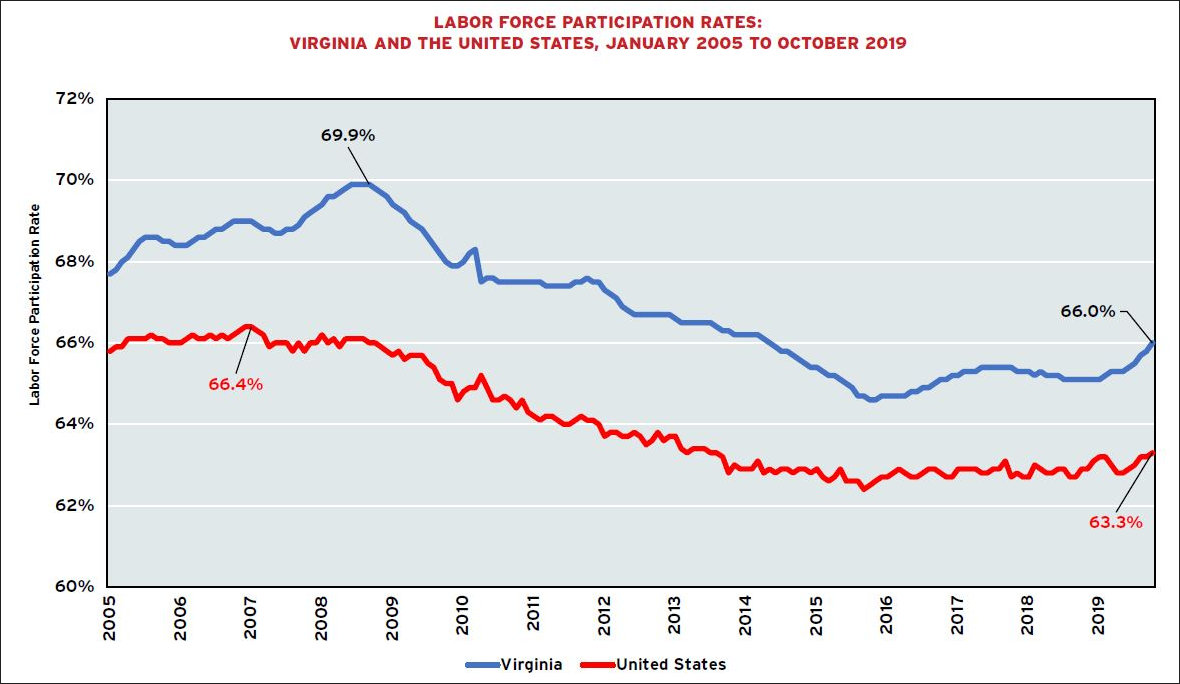

Unemployment can be a deceptive number. A low unemployment rate coupled with a low labor participation rate is not a sign of dynamism; it could indicate that a large percentage of workers are “discouraged,” have stopped looking for a job, and are scraping by on savings and/or government benefits. Nationally, the labor participation rate has declined over the past decade. In Virginia it has inched back up, hitting 66% this year.

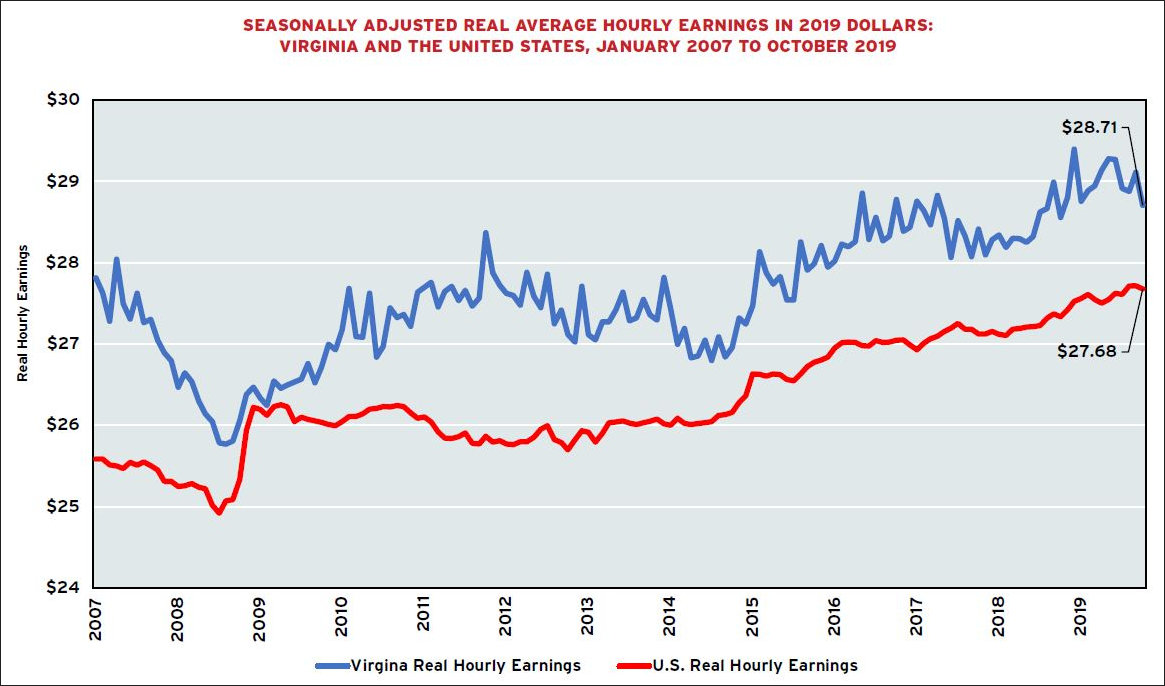

Economic prosperity depends upon more than job creation — it requires good jobs, high-paying jobs. Virginia continues to maintain an hourly earnings differential of about $1 — $28.71 compared to $27.67 — above the national average.

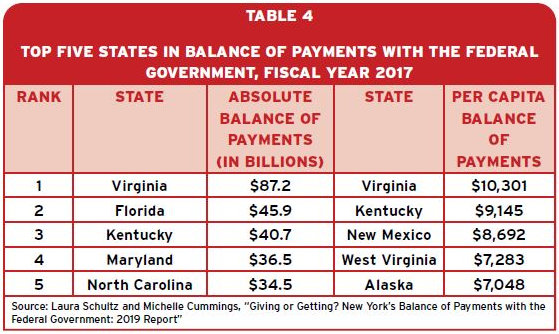

In sum, the economic picture in Virginia is looking better than it has in recent years. But the ODU report issues some warnings. For one thing, the commonwealth remains more dependent than any other state upon federal spending. If federal spending takes a hit — and the ODU economists warn that the bill for swelling deficits and national debts will come due one day — Virginia’s economy will suffer disproportionately.

This table shows the five states with the biggest “balance of payments,” indicating the largest gap between federal income taxes paid and federal spending. Discretionary spending such as contracts and awards (as opposed to mandatory payments like Social Security) are the most vulnerable to cutbacks in budgetary bad times.

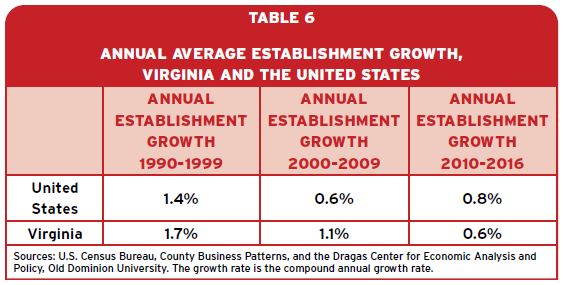

One other disturbing indicator is the slowing rate of new business formations as measured by “establishment” growth. (An establishment is a physical location where business is conducted or where services or industrial operations are performed.” In the 1990s, Virginia experienced a faster growth rate than the national average. But the state has lagged the national rate since 2000. The total number of establishments was lower in 2016 (199,548) than in 2007 (200,503).

The most positive indicator, not reflected in these statistics, is Virginia’s resurgence in “Best States for Business” rankings. The Old Dominion regained the top spot in the CNBC ranking this year. Plus, after a lengthy delayed reaction, Amazon decision to locate its HQ2 project in Arlington — creating 25,000 direct jobs, not counting indirect jobs — should start kicking in at some point.

Not long ago, Virginia had one of the strongest state economies in the country. The malaise of the 2010s may be the most prolonged slow-growth period of the post World War II era. Could Virginia regain its mojo next year? Depending on how long the federal government can prolong its deficit-spending binge — and there is no sign of fiscal restraint on the horizon — it could happen.