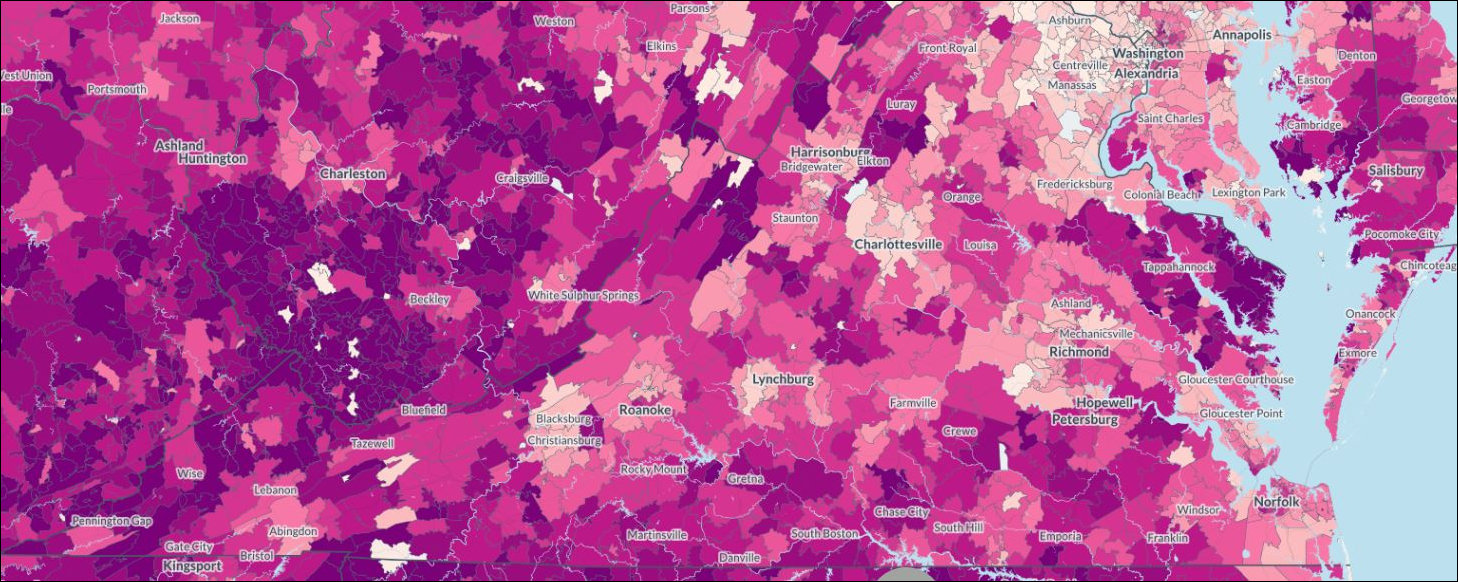

Student loan delinquency rate by zip code. Darker colors indicate higher rates. (Click for more detail.)

by James A. Bacon

Americans now owe $1.3 trillion in student loan debt, exceeding the amount they owe on credit cards ($700 billion) or automobile loans ($1 trillion). Unlike other forms of debt, student loans are disproportionately concentrated among young people. Further, student loans are uniquely onerous because the debt cannot be discharged in bankruptcy proceedings. In the past two decades or so, America has created a new indebted class — I call it the indentured servant class — where none existed before.

After decades of advocating the expansion of federal lending programs on the grounds that everyone who wants to attend college should be able to, America’s progressives are waking up to the idea that maybe the massive accumulation of debt is not such a good thing. Indeed, the student debt issue has become a major presidential campaign theme for the first time in American history with Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton vying to outbid the other with proposals for loan forgiveness, free college and the like. Progressives wouldn’t be progressives, of course, without turning massive student indebtedness, which they aided and abetted for so long, into a racial issue. Student loans, you see, constitute “structural racism.”

After an extensive analysis of the data, Marshall Steinbaum and Kavya Vaghul with the Washington Center for Equitable Growth have concluded that minority populations disproportionately suffer from high delinquency and that middle-class minorities seem to be the most adversely affected. “We believe that these two facts reflect the impact of structural racism in the U.S. higher education system, credit and labor markets, and distribution of wealth.”

Actually, I have observed previously that the piling on of student debt represents a form of “structural racism.” But rather than blaming credit and labor markets, I indict the U.S. system of higher education exclusively. One of the most proudly progressive institutions in the country is also one of the most racist — assuming we define racism the same way that progressives do, which is by the disparate impact institutional arrangements have on the poor and minorities.

Steinbaum and Vaghul have performed a useful service in building a map of student debt (from which the image above was taken). They analyzed each zip code in the country by median household income, racial composition, and student loan debt delinquency. (You can see the interactive map here.) Not surprisingly, they found strong correlations between household income, race and default rates.

Unfortunately, they superimposed upon the data their own progressive framework for analysis, citing discrimination in credit markets (minorities get less generous credit terms) and labor markets (minorities are less likely to get job offers) as important reasons for the higher default rates. Those are interesting claims, which may or may not be true — a good topic for a different blog post — but I think it’s fair to say that the most important factor explaining the higher default rate by minorities is the college completion gap.

The authors do acknowledge the reality of this gap:

African Americans and Latinos are, on average, less likely than white students to complete college once they start. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, in 2013 roughly 57 percent of recent African American high school graduates and 60 percent of recent Latino high school graduates were enrolled in college compared to 69 percent of white students. Yet the National Center for Education Statistics reports that for the 2005 starting cohort of college students, about 21 percent of African Americans and 29 percent of Hispanics complete a four-year institution within four years compared to a four-year completion rate of 42 percent for white students.

This is fundamental. The longer it takes to graduate, the more debt a student accumulates. Moreover, if a student fails to graduate and acquire the credential it takes to succeed in the job market, their debt is all the more difficult to pay off. All other factors pale in comparison.

So, the real question we should be asking is this: Why are blacks and Hispanics dropping out of college at higher rates than whites, and why do they take longer to complete their degrees? Are they less prepared academically on average than whites and Asians, perhaps because of the inadequate quality of their K-12 education? Do they take more remedial courses in college? Do they struggle with higher-level courses? Do they fail more courses? Do they get more discouraged and wonder what the hell they’re doing?

Rather than blaming credit markets and labor markets, perhaps we should take a closer look at the policies of America’s colleges and universities. To what extent, in their pursuit of diversity, do they admit minorities with lower SAT scores than the student average? If minorities do have lower SAT scores, do the colleges provide them additional support it takes to keep up — remedial classes, tutoring, mentoring, whatever — or do they let the students fend for themselves?

Here in Virginia, the University of Virginia stands out for the negligible difference in graduation rates between blacks and whites. Clearly, although UVa aggressively recruits minorities, it either (a) succeeds in recruiting minorities who are equally qualified academically, (b) provides the necessary support for those who aren’t as qualified, or (c) accomplishes some combination of the two.

If UVa is the gold standard for minority retention (not just recruitment), we should ask, how do other Virginia colleges and universities, both public and private, compare? Colleges recruiting minorities and congratulating themselves on their diverse enrollment, but then allowing minority students to struggle, drop out and accumulate massive, unpayable debt are guilty of what I call institutional racism. Such behavior is a stain that no amount of good intentions can wash away.

(Hat tip: Larry Gross)