Solar power is looking better and better by comparison to wind power, and that’s a good thing for Virginia.

Solar power is looking better and better by comparison to wind power, and that’s a good thing for Virginia.

In Germany, a global pioneer of wind power, hundreds of wind turbines are experiencing metal fatigue and other issues as they pass their 20- to 25-year design lives — and they are literally falling apart. Turbines are falling to the ground. Blades are snapping off and flying hundreds of feet. Razor-sharp glass fiber splinters have been documented to have flown 800 meters away. So far, no one has been hurt, but one expert speaks of a “ticking time bomb.” (Die Welt has the story here.)

Problems with an energy-production source often don’t become evident for decades. That certainly was the case with coal and oil. Now, a couple of decades after the widespread deployment of wind turbines, we’re learning about a downside of wind. Compared to Deepwater Horizon-scale oil spills and mountaintop-removal coal mining, flying turbine debris may be small potatoes. But as we think about our energy future, the comparison isn’t between wind and coal or oil — no one is building new coal or oil plants — it’s between wind and solar. The great virtue of solar panels is that they just sit there… except when hurricanes tear them off their mountings. But, then, high winds are a problem for wind turbines, too.

Assuming we can design and test turbines to withstand hurricane-force winds, there will be a place for wind in Virginia’s long-term energy future. Wind turbines work at night, which solar panels do not, so they can partially offset the daily drop-off in solar production. Furthermore, if Virginia taps large-scale wind resources, most turbines will be located offshore. Flying turbine blades are less of a problem when people are 20 miles away. But solar power poses none of these issues, and solar is being rolled out on a large scale today. Right now.

The biggest barrier to solar power in Virginia isn’t technology, it isn’t grid reliability (not at this stage of development) and it isn’t obstruction in Richmond. State law now proclaims large volumes of renewable energy to be in the public interest, and Virginia’s largest utility, Dominion Energy Virginia, is forecasting the deployment of more than 5,000 megawatts of solar in its service territory alone. The biggest barrier is local zoning codes, as we are reminded by a story today in The News Virginian.

The Augusta County Board of Supervisors adopted an ordinance yesterday by a narrow 4-3 vote that allows for the leasing of county land for solar energy use. However, critics said the requirement for a 1,000-foot setback from other residences will discourage solar development. The ordinance also does not allow for solar projects on land zoned industrial.

Roger Willetts, who owns the 44 acres in Stuarts Draft, said his property is taxed $6,000 a year by the county. But he said if a solar farm is allowed, he could generate $60,000 in revenue a year. “I think it is an appropriate use. It won’t employ anybody and it won’t have any bathrooms,” Willett told supervisors.

But under the ordinance approved Wednesday, Willetts’ property would be excluded because solar energy on industrial land is not allowed.

Augusta County, situated in a once-beautiful stretch of the Shenandoah Valley, is not a “rural” county with pristine viewsheds of farms and forests. It is characterized by what I call “rural sprawl” — scattered, low-density residential, commercial and industrial development smeared across the countryside. The viewsheds are despoiled already. Sad to say, solar farms aren’t any uglier than what’s already there.

Everywhere a developer proposes to build a solar farm — arguably the most benign form of energy production known to man — the NIMBYs come out and call for restrictions. NIMBYs don’t want gas pipelines. They don’t want electric transmission lines. They don’t want wind turbines. They don’t even want solar farms.

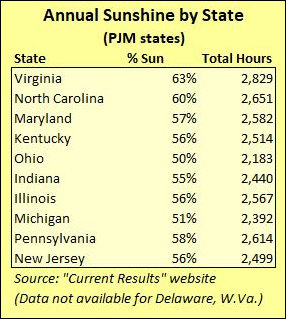

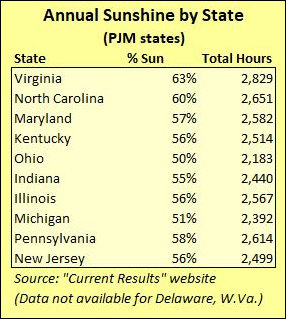

Ironically, solar power could be a boon to the sluggish economies of Virginia’s non-metropolitan cities and counties. Not only do Virginia’s electric utilities envision more solar, the potential exists for Virginia, long a net importer of energy from other states, to export solar power. Virginia is the southern-most state (excluding the northeast corner of North Carolina) in the PJM electric transmission region. For both political and business reasons, there is an insatiable demand for more renewable power within that 13-state region, which stretches from Virginia north to New Jersey and Illinois. Much of that demand comes from Virginia itself, the nation’s leading location for data centers, because West Coast cloud providers insist upon renewable energy sources. PJM creates a wholesale market for that region, which makes it easier for energy producers located within it to sell into the wholesale market than it is for energy producers on the outside.

While wind-swept Midwestern states in the PJM region are better situated for wind, Virginia is the best situated for solar. As the southern-most state, the Old Dominion has greater solar energy potential — more sunny days and a latitude closer to the equator — than its northern neighbors. As seen in the table above, Virginia has the highest percentage of sun — defined as the percentage of time between sunrise and sunset that sunshine reaches the ground — as well as the largest number of annual hours of sunlight of any PJM state.

Local government officials in Virginia should think of solar power as an economic development tool. Solar farms provide a royalty-income stream to landowners, and they augment the local tax base. While they create few long-term jobs, they do deliver a burst of short-term construction work. As utilities invest in grid modernization, Virginia can provide solar energy for its own needs — up to 30% of the electricity supply, some say, without diminishing grid reliability — and it can export green power to states to the north. This looks like a once-in-a-generation economic opportunity for rural Virginia. Let’s not blow it!

Concerns about the reliability of the U.S. electricity supply has popped into the news headlines recently. The problem isn’t terrorists or cyber-attacks, it’s the inability of electric grid to handle routine challenges. Earlier this month, a transformer fire in Manhattan knocked out electric power to about 73,000 customers. On the West Coast, PG&E is spending $2.3 billion to fix a backlog of deficiencies in its transmission and distribution system that contributed to the record outbreak of wild fires in California last year. Meanwhile, the company has announced its intention to preemptively turn off power on vulnerable circuits to limit wildfire risk.

Concerns about the reliability of the U.S. electricity supply has popped into the news headlines recently. The problem isn’t terrorists or cyber-attacks, it’s the inability of electric grid to handle routine challenges. Earlier this month, a transformer fire in Manhattan knocked out electric power to about 73,000 customers. On the West Coast, PG&E is spending $2.3 billion to fix a backlog of deficiencies in its transmission and distribution system that contributed to the record outbreak of wild fires in California last year. Meanwhile, the company has announced its intention to preemptively turn off power on vulnerable circuits to limit wildfire risk.